Municipal recreation agencies are keeping close watch on private-sector detractors

Sticks and stones may break bones, but words can take an even more devastating toll. Just ask the dozens of municipal recreation agencies nationwide whose large-scale capital projects - ranging from small aquatic facilities to community recreation centers - have been derailed, thanks to opposition stirred up by local and national interests.

The forces behind the anti-public recreation campaigns vary in form. In some communities, a resident opposed to recreation facility construction in his or her neighborhood may represent the lone naysaying voice (see "Yard Work," p. 68). In many cases in recent years, owners of private, for-profit fitness centers have launched joint attacks in their locales. Presenting an even greater challenge is the International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association (IHRSA), which on several dozen occasions has provided financial and legal support to health club owners fighting to shut down public recreation projects.

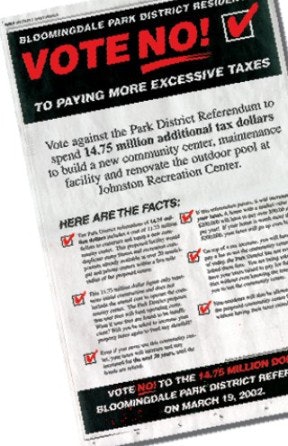

The most successful campaigns will typically blanket a community with a snowstorm of slick marketing materials merely weeks before a referendum vote, condemning the project for anything from "misappropriation of taxpayer funds" to the duplication of recreational programming already available in the private sector - or, more often, both.

Many residents read the fliers or newspaper advertisements and become outraged, feeling betrayed by their civic leaders. Others are left confused; they want to believe their municipal government is working for the greater good of the community, yet find it difficult to overlook the persuasive allegations made by individuals who say they too are taxpaying residents.

"When somebody gets up in a public meeting and makes these claims, it's hard to counter them," says Mike Shellito, director of parks and recreation in Roseville, Calif. "It's a difficult circumstance."

It's especially difficult when public recreation departments are limited in their capacity to respond to such claims. It's considered improper for government agencies to spend already scarce public funds on marketing campaigns similar to those launched by their private-sector detractors.

"What irritates us is when these groups give out misleading and false information. We think that's highly unethical," says Ted Flickinger, executive director of the Illinois Association of Park Districts, who believes that despite the restraint public recreation agencies must employ, too much is at stake for them to do nothing at all. "We're going to try to solicit funds from other sources - vendors and Friends of Illinois Parks organizations - so that when this happens, we can help our local districts get the facts out to the public."

The IAPD is also educating recreation departments on such topics as devising project financing strategies and weathering public controversy. Flickinger says that in no way is his organization looking to pick a fight or wage a public policy war with IHRSA or its members. "But if it continues, we're going to have to be in that kind of mental framework and come through on some specific things to help our agencies," he says. "We're making this one of our priorities."

Also among the IAPD's priorities is relating to the Illinois parks and recreation community the seriousness of this issue. Flickinger believes that many recreation professionals are still somewhat naïve to the difficulties their colleagues involved in facility planning and construction are encountering, thanks to negative campaigns in his state and elsewhere. "Unfortunately, some of the people in our field consider parks and recreation to be as sacred as motherhood and apple pie, and that everything is very positive," he says. "Well, now you can get hit on a lot of different fronts. They've got to wake up and get out there and tell their story to the public. They've got to tell them what we're all about."

While the IAPD is considering adding a forum to its web site dedicated solely to the public-private controversy, other state recreation agencies are also beginning to place a greater focus on supporting member departments whose projects are in jeopardy. State agencies in Ohio and Pennsylvania, for example, have organized committees designed specifically to address these issues.

Sarah Clugston, recreation director in Hampden Township, Pa., says that such a committee sponsored by the Pennsylvania Recreation and Park Society has even turned to National Recreation and Park Association officials for advice and a little political muscle. "We wanted them to tell IHRSA to take a hike," she says, adding that the committee's request was turned down. "It just doesn't seem to be sinking in with NRPA. Maybe it has too much to lose."

It's not that NRPA is shying away from the public-private issue, says Barry Tindall, director of the association's public policy department, but rather that becoming intensely involved in the debate might equate to a poor use of the association's resources. "We have chosen not to make it a national debate. With about 30,000 units of local government in this country, it'd be foolhardy for NRPA to be a traffic cop on the one hand and an advisor on the other," he says, citing NRPA's history of lobbying for parks and recreation interests on Capitol Hill. "From the time this organization was created in 1965, we have always argued for and worked to maintain local, state and national recreation prerogatives."

And it's not that NRPA hasn't made past efforts to collaborate with IHRSA, says Tindall. The associations' leaders have met several times in the past 10 years in an effort to devise some sort of an agreement, only to come away with nothing. "We're trying to convince IHRSA that the demands are so great for people to have access to health and wellness resources that rarely does a park and recreation agency have anything to do with the rise or fall of a private health club," he says. "The reality is that Americans need far more rather than less. This is more important than trying to protect the investment rights of entrepreneurs in the health and wellness business. Americans are in pretty lousy shape."

It's true that the demand for recreation facilities and programs has jumped significantly in recent decades. This trend is driven by several factors, including an increasing awareness of the need for health and wellness, and the proliferation of suburban communities. "Given the nature of business and technology today, people can live almost anywhere they want to," says Webbs Norman, the Rockford (Ill.) Park District's executive director. "Quality-of-life issues in communities are significantly more important today than they used to be and they will increasingly be so in the future."

Take Roseville, Calif. - a suburb of Sacramento. Roseville's population has nearly doubled since 1990, from 45,000 residents to 80,000. Meanwhile, city officials have committed themselves to developing parks and recreation facilities to keep pace with demand.

Two years ago the Roseville Sports Center opened, offering residents a 27,000square-foot facility where they could play, exercise and gather. While its largest component is the gymnasium, the Sports Center also features a 2,300-square-foot fitness room with about 20 pieces of cardiovascular equipment, which remains a bone of contention with local for-profit clubs. "It's not like our fitness room is 12,000 square feet with 150 machines," says Shellito. "I don't think having a treadmill should be the exclusive domain of a health club."

Besides, Shellito continues, the Sports Center - like the city's four outdoor pools - is designed to appeal to a broader demographic than any of the local for-profit health clubs. "There are a lot of programs that we offer that the private sector either cannot provide or has no interest in providing," he says. "They're not interested in providing open swim time in the afternoons for kids from low-income neighborhoods. They don't want that. It's not profitable and it would detract from their health club experience."

To address Roseville's growing need in aquatics programming, the city spent the first half of this year developing an ultimately unsuccessful partnership with a local YMCA chapter to build an $11 million, 46,000-square-foot indoor aquatic/ community center. Under the partnership, the facility would have been built on city-owned land, with each organization paying the construction costs for its respective component: The city would pay for the pool, and the YMCA for the community center. The YMCA was to be responsible for all facility operations, thus requiring no subsidy from Roseville's general fund. "It would've saved $250,000 a year," Shellito says. Another condition working to the city's advantage would've required the YMCA to operate the facility's aquatics programming exactly as the city dictated, or operational control would be returned to the recreation department.

Despite the potential benefits this joint venture held for both parties and their constituents, a group led by a health club owner in neighboring Rocklin organized what Shellito estimates was a $100,000 public relations campaign aimed at scuttling the project before it even got off the ground. The accusations flew, says Shellito, and mailers were sent out claiming that "the city was giving money away to a multimillion-dollar corporation to build a fitness center." In the wake of severe public scrutiny, YMCA officials pulled out in June.

"They decided it wasn't in their interest - and frankly, it wasn't in ours either - to fight this public-relations battle that seemed to have a fairly significant war chest dedicated to derailing the project," Shellito says. "Their focus and our focus is on serving kids. We wanted to build a pool because we're stretched thin in aquatics, despite having four pools. We're teaching 1,200 kids a day, yet we're turning away 200 more at registration for each two-week session. We need a pool, and this was a way it could've happened for us. It's disappointing because in the end, the losers are the members of the community."

Many public recreation professionals find it ironic that for-profit clubs paint themselves as the ones getting a raw deal. Arguments like IHRSA's - which portray public recreation departments as "tax-exempt entities that are cutting into their business" - "fail to understand what government is all about," Tindall says.

As Tindall notes, as far back as the early 1900s, the first public recreation agencies were established with the goal of addressing public health and welfare. Roughly a century later, the mission of departments everywhere remains focused on providing health and wellness opportunities for residents of their respective communities. As the years have progressed, so have the recreational needs of individuals everywhere, requiring municipal agencies to adapt.

Little more than preserved plots of grass and woodlands, the parks of 50 years ago have gradually been replaced by complexes that feature interactive playgrounds, sports courts and fields, and trail systems. Pools, too, have evolved, from their strictly rectangular forms to areas for interactive play. And while community centers offering nothing more than gymnasium space and meeting rooms might have sufficed several decades ago, people now expect their community buildings to be everything-under-one-roof facilities. "If you want to make sure that you're playing to the whole community, you've got to have a little bit of everything for everyone," says Clugston, "so that anyone who wants to use the center can."

In September, Clugston's Hampden Township recreation department scored a victory when that township's board of commissioners voted, 3-2, to continue preliminary work on a 60,000-square-foot community recreation center project. The facility will include an indoor aquatics area with both leisure and competitive components, two gymnasiums, an elevated track, a fitness area, teen and senior centers, multipurpose rooms and administrative offices. According to Clugston, no taxpayer money will be used to finance construction, and excess revenue from the township's golf course and outdoor swimming pool will be used to subsidize facility operations.

Despite these moves, the project has withstood considerable pressure from the owner of a health club in a neighboring township who has charged the recreation department with misuse of government funds and unfair competition with his facility. To appease the club owner, Hampden Township officials agreed to downsize the fitness area to 3,600 square feet and eliminate the free-weight area from the facility's plans. The center will carry only a limited selection of cardiovascular machines.

"We play to a completely different crowd. This is a community center. The Spandex can stay at the health club," Clugston says. "The people who we're catering to aren't going to want to run on a treadmill next to somebody in Spandex because they're going to feel intimidated. We're targeting those people - like me - who have several grown children and have been out of shape for a long time. We also want to have a place for kids and a place for seniors to socialize."

Even though some public recreation professionals are gathering forces to do battle, most within the field still point to partnerships as a less tumultuous, and ultimately, a more productive alternative. Historically, partnering with other nonprofit organizations - public or private - has been the most logical choice for many municipal recreation agencies.

Take, for example, the Aztec Family Center, currently under development in Aztec, N.M. The center's various components are to be jointly owned and operated by four separate nonprofits: the City of Aztec, a local Boys and Girls Club, Aztec Municipal Schools and San Juan College, a community college based in nearby Farmington. The community and educational center components - the first and second phases of the four-phase project - are already complete. The facility will add a library and a fitness center and pool in two later stages. "None of the individual entities had enough funding available to build their own facility," says Ed Bledowski of Farmington-based DLR Group, the project's architect. "This plan allowed them to pool their resources and develop a true family center offering education, recreation and sports."

The advantages of forming program and facility partnerships with nonprofit organizations are no secret to municipal recreation agencies. However, looking to the financial benefits of subscribing to a "strength-in-numbers" philosophy is only part of the equation, says Norman, whose Rockford Park District has focused on pursuing and establishing partnerships with the for-profit business community that improve that city's overall experience. Park district officials there sponsor a forum with about 30 local business leaders each month. "The park district was formed by members of the business and industrial community because they realized the need for activities and facilities for the health and well-being of their employees and their families," he says. "That partnership has existed for the past 93 years and it's very strong today. The business and industrial community continues to be very supportive of what we do."

Can that kind of relationship be extended to for-profit health clubs and fitness centers, and perhaps foster partnerships between these entities and recreation departments? "Absolutely, I think that can happen. Doing so will enhance services that people are beginning to expect," says Shellito. "My perspective is that you make the pie bigger and you get more people involved with exercise, fitness and sports. It'd be good for clubs if there was a return on their investment, and good for us if open access was guaranteed. It couldn't be exclusive. We'd still have to carve out time for youth basketball."

"In this day and age, I don't care whether you're a public or a private group, you should be working with as many organizations as you can," says Flickinger. "It just makes sense. There are a lot of resources out there to make the community a better place. That's what we should all be working for."