America's soldiers and sailors prepare for friendly athletic competition with the rest of the world

The objective was to gather armed forces athletes from around the globe in a quadrennial show of unity and solidarity through sport - and that's exactly what the 1995 and 1999 Military World Games quietly accomplished. Now, with the third installment of the Games slated for Sept. 13-23, 2003, in Catania, Italy, and many Western countries on high alert because of heightened terrorist activities, the message of the Games may resonate louder than ever.

"Rather than doing battle on the battlefield, we do battle on the sports field," says U.S. Armed Forces Sports Secretariat Suba Saty. "I'm not so naïve to think that the Games are going to solve the world's problems, but I tell our athletes that this is a great opportunity to show the rest of the world what the United States is all about and to learn from other cultures."

The Military World Games, the second largest international athletic event after the Olympics, is the brainchild of the Conseil International du Sport Militaire (CISM), which has close ties to the International Olympic Committee. Headquartered in Brussels, Belgium, CISM counts 123 member nations and organizes approximately 20 annual military world championships in 25 sports. Those numbers vary from year to year, depending on the number of participants and whether a country is available to host a specific event. Some countries, including Iraq, have had their memberships suspended for various reasons and are prohibited from CISM-sponsored competitions, including the Games.

In 1995, the Military World Games were held in Rome, Italy, and attracted about 4,000 athletes from more than 80 countries for what CISM officially called a celebration of "Friendship Through Sport." U.S. athletes placed eighth in the medal count, behind front-running Russia. The 1999 Games were held in Zagreb, Croatia, which saw more than 6,700 athletes compete from 82 countries - including almost 300 from the United States, which placed seventh in the overall competition, once again behind medal-count leader Russia. At the time, the United States boasted a substantial military presence in the Balkan region, but Saty says Croatia wanted to prove to the world that the country could host an international athletic event and be a safe place to visit.

While the total number of participants for the 2003 Games (which will include competition in 11 sports) won't be determined until next August, administrators overseeing sports programs within the five branches of the U.S. military don't expect the threat of war or terrorism to hinder the event. "I don't think it's the soldiers and sailors who have big international issues; it's the politicians who have the big issues," says John Hickok, head of Navy Sports. "The athletes just want to compete. They may never be Olympians, so this is their Olympics."

That said, many Military World Games participants from other countries (up to 70 percent, by some estimates) are also Olympic athletes. In the United States, the Army has produced 444 Summer or Winter Olympians since 1948. Even Gen. George S. Patton was a modern pentathlete, finishing fifth at the 1912 Olympic Games. By comparison, the Navy fields an average of two or three Olympians every four years.

To this day, the Army and Air Force are the only U.S. military branches to offer formalized world-class training programs in which armed services personnel are stationed at specific facilities based on their athletic abilities. Additionally, other athletes from those branches who aren't in world-class training programs - namely teamsport players, as well as athletes in less popular individual sports - are culled from those branches' regular ranks. The same is true for all athletes in the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard, who must apply for team positions and cover their own expenses. "That's why Armed Forces athletics is so incredible," Saty says. "These people are training on their own."

F or many U.S. athletes, the journey to next year's Military World Games will be just as challenging as the history of the Games themselves, which required decades of tenacity on the part of organizers. In the aftermath of World War I, General John J. Pershing, commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force during that war, established the Allied Forces Sports Council in 1919 to break down cultural barriers and promote friendship among soldiers of the Allied Forces. U.S. General Joseph McNarney furthered Pershing's fledgling concept in the wake of World War II by developing the short-lived Military Sports Council in 1945.

Finally, during a 1948 fencing tournament in Nice, France, the participating countries of Belgium, Denmark, France, Luxembourg and The Netherlands formed CISM, which has been expanding for the past half-century.

While CISM's roster of Olympic events and military sports (which include military pentathlon, lifesaving and parachuting) consists primarily of non-winter sports, the organization added the World Military Ski Championships in 1954. On a much smaller scale than the World Games, this annual competition includes men's and women's events in crosscountry skiing, giant slalom, biathlon and military patrol (another skiing and shooting sport). Today, CISM is attempting to gain more female participants, as many countries' militaries are just beginning to diversify their populations.

The United States has been active in CISM competitions since the organization's beginning, and it hosts one CISM championship each year. (In 2002, it was tae kwon do, held last month at Ft. Hood, Texas.) Athletes from all five branches of the U.S. military participate in CISM competitions to varying degrees. Unlike Olympians and most other athletes, however, military athletes typically play abbreviated seasons in which tryouts, training camp, practices, competition and championships all take place within about six or seven weeks. This is because active-duty personnel cannot afford to be away for long periods of time and must therefore squeeze their seasons into small windows of opportunity.

Take the 2002 men's and women's volleyball seasons. Tryouts, training camps and practices were held between Aug. 16 and Sept. 8 at bases across the country, chosen by each branch. Then, a week of competition between the Army, Air Force, Marines and Navy/Coast Guard teams commenced on Sept. 8 at Naval Support Activity Mid-South in Millington, Tenn., running through Sept. 15. (Coast Guard athletes participate on Navy teams in all sports except rugby.)

Based on those competitions, U.S. Armed Forces men's and women's teams were chosen to represent the United States at the CISM World Military Volleyball Championships held in Constanta, Romania, from Sept. 20 to Oct. 2. Team expenses were picked up by the host branch, the Navy in this case, which then billed the other services for costs incurred during the event.

Some members of armed forces teams may not be able to participate in CISM competitions if military duty calls, so alternates are chosen in team sports. (In individual sports, alternates are named only if they meet specific criteria.) "We never know until really the last day of a national tournament who's going to go to the CISM championships," Hickok says. "Even though they are involved in sports, they have another job to do first. If a Navy athlete is on a ship in the Persian Gulf and his commander says, 'We need him to fight terrorism,' when he's scheduled to play sports, he doesn't play sports."

For many military athletes, sports are considered a full-time extracurricular activity. "I haven't a clue what they do during the off-season," Hickok admits. "But it's obvious in training camp who has done nothing all year."

Sailors and soldiers are encouraged to maintain their skills by training on their own or hiring a trainer, or (in the case of team sports) joining local park and recreation leagues.

Of the U.S. military's branches, the most athletically active is the Army. The World Class Athlete Program (WCAP) accepts exceptional soldier-athletes (including reservists) and provides a training ground for national and international competition. "I don't even plan on winning an armed forces boxing or wrestling match, because the Army's usually always going to win," jokes a sports administrator from another branch of the armed services.

Established in 1978, the Army's WCAP is a three-year program that can accommodate up to 125 assigned athletes. It currently includes 80 who participate in 12 Olympic sports, including boxing, wrestling, modern pentathlon, tae kwon do, and track and field.

All WCAP training takes place at the program's Ft. Carson, Colo., headquarters, except for track and field participants, who train at satellite locations in California, Colorado and Texas. A handful of other WCAP athletes are stationed at locations near facilities where they receive proper training for international competition. Non-WCAP athletes who participate in all-Army tryouts or apply for specialized sports must pay for their own training.

WCAP receives about $200,000 annually in appropriated (taxpayer) funds for care and upkeep of a barracks, and about $1 million in non-appropriated funds for training, competition, equipment and coaches' salaries, according to Paulette Freese, director of the Army's WCAP. Non-WCAP athletic programs in the Army and Air Force also have their own budgets.

The Air Force's World Class Athlete Program is much smaller than the Army's, and it revolves around a series of satellite facilities located in various parts of the country, usually determined by the location of the best available training. For example, a judo competitor is stationed in Japan, says Steve Brown, chief of Air Force Sports, but the other 17 Air Force WCAP participants (specializing in six sports) are stationed in the United States. Additionally, about 300 other Air Force athletes apply for Air Force teams each year, Brown says.

The Air Force WCAP program began in 1995 and operates on a budget about one-third the size of the Army WCAP, Brown says. Usually, the roster of Air Force athletes is larger, but because of increased mission requirements abroad and stateside, numbers are down this year.

Meanwhile, the Marine Corps, Navy and Coast Guard field considerably fewer elite athletes than the Army and Air Force, in large part because of smaller budgets, fewer members or both. The Navy Sports program is similar to the Army's WCAP only in concept. "My program is designed to take the quality athletes who have Olympic potential and work with them," Hickok says. "But our people are basically holding down two full-time jobs." Even Olympic-caliber athletes are expected to train on their own, with the Navy covering expenses only for all-Navy teams that participate in national competitions. Each year, an average of about 250 Navy personnel make the various U.S. armed forces teams.

The Coast Guard, which program analyst and sports director Chief Warrant Officer Harry George says receives only $5,000 a year for its athletic program, co-ops with the Navy in most national competitions. Navy athletes welcome Coast Guard athletes with open arms, Hickok says. "The Coasties want to play, and we want to help them," he explains.

Still, George is pushing for the government to sanction more Coast Guard sports. "We have a lot of athletes, but I think they want to play on a Coast Guard team, not a Navy team," he says. "They're Coast Guard people, not Navy people." George maintains a list of how many Coast Guard athletes try out each year for Navy teams as a way to gauge interest in a particular sport. In 2002, 51 Coast Guard athletes applied for Navy teams; 16 made those teams. If interest in specific sports is great enough, as it is in rugby, George says the Coast Guard may eventually be able to field its own teams in those sports.

Meanwhile, about 100 Marine athletes competed in 2002 armed forces competitions, many of them in boxing, wrestling and running. The Marine Corps provides full-service training facilities for those programs at select bases around the country. Athletes in other sports, in other branches of the U.S. armed services, are expected to train on their own.

In an effort to attract younger Marine athletes, the Corps recently began supporting competition in a variety of non-CISM activities that officials call "expanded sports." They include rodeo, the Ironman triathlon, BMX racing, judo, skeet shooting and archery.

The Military World Games, unlike the Olympics, aren't expected to ever become a huge spectator event. Interest in the Games comes mainly from European countries, and for the most part, the proceedings remain "a military thing," Saty says.

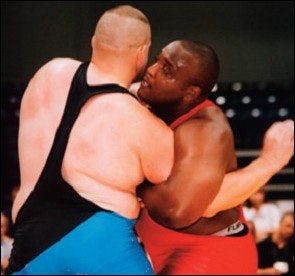

Civilians rarely attend the Games, let alone national championships. In the United States, military sports administrators say, you can often count the number of civilian spectators on two hands (sometimes even on one hand). Boxing, however, draws crowds to any military base in the country, and is considered the U.S. armed services' most spectator-friendly sport.

In a sense, the Military World Games may be among the last amateur sporting events for adults that remain truly amateur. Lacking throngs of fans and major media hype, they exist almost exclusively for the athletes involved as they compete for both personal and national pride.

Which raises the question of whether competitive athletics are necessary in the lives of military men and women whose primary duty is to serve and protect their country. Despite the Department of Defense's 1987 directive "to ensure that the U.S. Armed Forces are appropriately represented in … international sports competitions," the attention placed on military sports remains the subject of ongoing debate within the armed services, particularly when an athlete is paid to leave his or her base, platoon or ship, while fellow soldiers or sailors must pick up the slack. That reportedly still causes some grumbling among nonathletes.

"The Marine Corps priorities are clear: Make Marines, win battles and return responsible citizens to the USA," says Jim Medley, a sports specialist with the Marine Corps. "That said, the Marine Corps considers every Marine to be a warrior athlete. Participation in organized athletics is a tool in the development of a 'fighting spirit.' "

Adds Hickock, "I like to see soldiers and sailors carrying guns and sailing ships, too. That's why they're here. But you know what. We can usually afford to give them up and let them compete."

To that end, many armed forces sporting events have been shortened in recent years. Some tryouts and training camps that once ran longer than a month now last about three weeks, Brown says. Some competitions, particularly in individual sports that don't require much team preparation (cross country and marathon, for example) can be completed within a week or even days.

Still, the issue is a touchy one, as sports remain an integral element of the military experience and provide an outlet for talented athletes. In fact, it could be argued that the Army and Air Force see so much value in military athletics that some members of those branches can opt to make athletics their military job. Says Brown, "We are essentially entitling our folks to the same benefits as their civilian counterparts."