Universities Can No Longer Justify Using Athletic Training Students in Place of ATCs

For many years, athletic departments and athletic training education programs across the country have utilized athletic training students to help provide certain aspects of health care to athletes. However, the implementation of new standards and guidelines required for accreditation of athletic training education programs (such as those developed in 2001 by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs) - as well as other educational reform measures - are causing athletic training educators to rethink the use of students.

Under current standards and guidelines, the internship route leading to certification as an athletic trainer has been eliminated, and anyone pursuing certification as an athletic trainer must now graduate from an accredited athletic training education program. In addition, the National Athletic Trainers Association Board of Certification (NATABOC) no longer requires athletic training students to document a minimum of 800 clinical experience hours before sitting for the examination. Completing these hours had long been the major rationale for placing students in many of these unsupervised situations. The educational program and the NATABOC requirements have become competency based, thereby placing more importance on the quality of the clinical experience and less importance on the number of hours completed.

The reason these policy changes are so important is that athletic training students traditionally have provided a significant amount of unsupervised care to athletes when they "cover" practices and events, or when they travel (also without supervision) with athletic teams. Although many school administrators claim that these athletic training students are to a certain extent supervised by certified athletic trainers (ATCs), many athletic programs in effect use these students as inexpensive athletic training staff. Athletic directors and other school administrators must now reconsider how they can continue to provide adequate health care for their athletes.

According to a National Athletic Trainers Association (NATA) task force established to develop recommendations for the prevention, assessment, care and appropriate management of athletic-related injuries, there is a huge discrepancy among school athletic programs in the quality of care provided athletes. This is a problem, as schools' legal duty to provide their athletes with proper medical care is well established. According to the NATA, the recognized appropriate medical care of athletes requires schools to provide more than basic emergency care during sports participation. Ideally, the school should have a designated athletic health-care provider who is qualified to handle a wide spectrum of tasks, including: • determining the individual's readiness to participate; • establishing protocols regarding environmental and emergency conditions; • providing for on-site recognition, evaluation and immediate treatment of injury and illness with appropriate referrals; and • advising on the selection, fit, function and maintenance of athletic equipment.

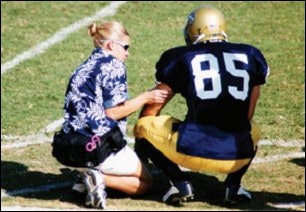

It is clear that the old structure of allowing unsupervised athletic training students - that is, students having no direct visual and auditory contact with the clinical supervisor - to work games and events does not meet the legal duty schools owe their athletes. Clinical instructors must be close enough while supervising athletic training students to physically intervene in order to protect the patient.

Administrators must therefore determine whether they will hire more certified professionals or legally expose themselves by continuing to rely on unsupervised and presumably less-prepared students. The question is especially critical for weekend, early-morning and late-evening practices that occur after the athletic training rooms are normally closed - the times to which athletic departments have typically assigned students. If a school is still going to place athletic training students in these settings, administrators should know that students cannot legally perform many of the duties of a certified athletic trainer.

An important distinction must be made between students who are used to covering intercollegiate athletics in an assisting capacity and those who are being used in place of an ATC. It is crucial, therefore, to clearly define the role and expectations for athletic training students. Foremost, it should be clear that these students are there only to provide necessary first aid or to implement emergency action plans. For example, qualified athletic training students could work in a "first aid/first responder" capacity with well-defined limitations during hours when they are not directly supervised by certified athletic training staff members. They should be trained in emergency health care (including CPR and AED competence), have updated immunizations, and be current with their bloodborne pathogens training. First responders may, as the NATA Clinical Instructor Educator Workshop Manual states, "stabilize, provide immediate care and summon assistance when injury occurs." Although first responder experience may be valuable for the student, under the current guidelines that role is adjunct to the academic program and is not considered a required part of the student's formal education.

If athletic administrators do choose to continue to use students to provide healthcare coverage and services for their athletes, they should make sure all staff members (especially coaches) understand that students should not be expected to provide unsupervised treatments or rehabilitation, or make any return-to-play decisions for the athletes. An example of a job description might read as follows:

Students serving in the role of first responders may perform the following:

1) Apply prophylactic taping/wrapping procedures 2) Use preventative warm up/stretching techniques 3) Apply first aid 4) Initiate an emergency plan.

It is also recommended that it be clearly stated what these first responders may not perform. For example:

Students serving in the role of first responders may not:

1) Use any therapeutic modalities 2) Apply therapeutic exercise 3) Make return to play decisions for injured student-athletes.

It is recommended that any such document be reviewed and approved by the institution's legal counsel.

The bottom line is that schools have a legal duty to provide appropriate medical coverage and care to their student-athletes, and they cannot meet this duty by using students in place of certified professionals, particularly in the area of health care. Certified athletic trainers are medical professionals who specialize in the prevention, assessment, treatment and rehabilitation of injuries and illnesses that occur to athletes. No other medical profession would allow students to provide care to patients without appropriate supervision.

As for the argument that "we've always done it that way," this is no longer an acceptable answer. If administrators want to continue using unsupervised students to provide inappropriate health-care services, they should know that they are exposing themselves to a potentially expensive lawsuit.

Kent Scriber ([email protected]) is a professor and director of the Ithaca College Athletic Training Education Program. Attorney John T. Wolohan ([email protected]) is an associate professor of sports law in the sport management and media department at Ithaca College.