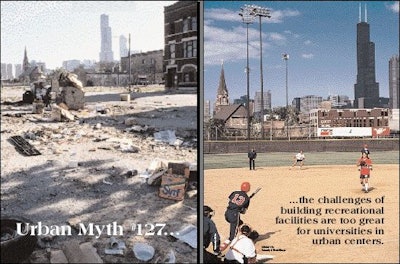

The challenges of building recreational facilities are too great for universities in urban centers

On the preceding page, you see a portion of the Chicago landscape that has given way to what you see on this page: A new field shared by the University of Illinois-Chicago women's softball team and the recreation department. The field, which opened in 1996, actually is part of a five field complex that includes two other athletic fields (men's baseball and varsity soccer), two multipurpose fields for recreation and several ancillary buildings. When the women's softball team is away, you might see intramural softball championships played here or, when school's out, games played by participants in UIC summer youth programs, cheered on by members of this southside community.

It's the same all over. Despite many challenges, universities in urban locations are building recreational facilities to "capture" their commuter students and form a more cohesive campus community. At the same time, the difficulties in land acquisition and project management are leading to more partnerships with local civic groups, bringing campuses and surrounding communities closer together.

The challenges are many, beginning with the limited amount of available space on which to build, as Lee McElroy, athletic director at American University in Washington, D.C., says.

"You've got students, you've got athletic teams, you've got staff and you usually also have community members to satisfy," says McElroy. "Many institutions struggle to respond to all the issues involved, and in some cases, the courts get involved."

Eric Huth, who manages the new Aztec Recreation Center at San Diego State University, can tell you all about that. His department endured a nine-year delay in completing the center as a result of a variety of legal issues, mainly centered around Cox Arena at Aztec Bowl, the arena portion of the project.

SDSU is located on more of a suburban site, but it shares many of the problems faced by urban universities. The school serves 30,000 students, 90 percent of them commuters, and the campus is hemmed in by freeways, private homes and shopping malls. Formal rec facilities are nowhere near big enough for a student body of that size, green space for unsupervised recreation is virtually nonexistent and the parking situation is nightmarish.

And yet, in the center of all this clutter stands the Aztec Bowl, the home of the school's football team until it began playing its games at Jack Murphy (now Qualcomm) Stadium. Since the football team's departure the Aztec Bowl was being used as a site of club-team and intramural contests, but it was otherwise "a big hole in the center of campus," as Huth says, a prime location for a combination arena-recreation center that could become a magnet for keeping all those commuters out of their cars and on campus.

The Aztec Bowl is on the National Registry of Historic Places, however, largely because of a speech Pres. John F. Kennedy gave there a few months before his assassination in 1963. Student protestors argued for its preservation and eventually sued the university; the settlement agreement placed the arena in the open end of the stadium horseshoe, with a concrete parking lot where the field used to be. Now the students have their new arena and 76,000-square-foot rec center, for which they're paying $47 a semester each to pay off a $52 million bond.

Northeastern University's year-and-a-half-old Marino Recreation Center owes its existence on Boston's Huntington Avenue to an earlier battle between the university and area residents. In the early '90s, the university designated the site (then a parking lot, one tennis and two basketball courts) as a new campus residence hall, but neighborhood residents charged the administration with being lax about policing students who neighbors said were overly rowdy and noisy. The community group's subsequent restraining order helped put an end to the project before it even began, and the school began contemplating other uses for the site.

Recreation Director Gene Grzywna says the community's concern over the site's eventual use led the rec department to forge a better relationship with residents. They both agreed that the site, as was then configured, was becoming a hangout for neighborhood youths and a suspected location of illegal activities. But the university, already stung once, tried to "welcome the community with open arms," as Grzywna says. In spite of concerns among students and administrators that space in the new 81,000-square-foot center was limited, the rec department agreed to allow 50 Boston residents into the center free every day, on a first-come, first-served basis. Residents trade their driver's license for a lock and towel, and sign a waiver their first time in. More than 3,000 different people have taken advantage of the program.

"The beauty of it," says Grzywna, "is that we open the doors at 6 a.m., and in the colder months, by 6:05 or 6:10 we've hit our 50 for the day. We let them in during what is normally our slowest time, so it never impacts us, plus it's a 'good neighbor' thing for the university."

When the 50 limit is reached, out comes the sign telling residents to try again tomorrow. "Given that it's free, it's kind of hard for them to complain - although I have had people come up to me and say, 'I'm a taxpayer of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, how come I can't use the facility.' " Grzywna says. "I kindly point out to them that they can if they show up earlier, but since we're a private school, nothing entitles taxpayers to use our facilities."

Urban institutions wanting to join the rec facility building boom deal with space constraints and security issues to a greater extent than their suburban, college-town or rural counterparts, but their biggest challenge often involves the neighborhoods in which they want to build. Paul Wiese of JJR Inc., the firm responsible for the UIC field complex and similar outdoor venues at Northwestern University and Loyola University, calls it the most critical component of all three projects.

"These are institutions that have long-term interest in development, and unfortunately, communities generally are opposing whatever universities want to do," Wiese says. "They have a mentality that universities try to swallow up the community, which I think is inaccurate, but in some respects maybe it's a little bit true because they do need land to provide for new facilities. I know Loyola in particular has put tremendous effort into trying to show the school's neighbors that they're good neighbors, but at the same time Loyola is even more landlocked than Northwestern, and they're desperate for land."

In the case of outdoor fields, universities can point to the green space as benefiting the community even if the community doesn't have complete access to it. With indoor rec centers, however, all universities have to offer communities in return for the land is access - and many are unwilling to share.

"They're building these things because their students have nowhere to go," Wiese says. "In the case of athletic facilities, varsity programs don't even open up their facilities to other students, let alone open them up to the neighborhood."

Temple University's 59,000-square-foot rec center opened in February, just a small part of a project that included a 10,000-seat basketball arena, the Forum at the Apollo. (A field house breaks ground later this month.) The university had long owned the land, and had previously knocked down a few vacant rowhouses to turn it into a parking lot, and so didn't face community opposition to its master plan.

The issue of community access was discussed, but according to Recreation Director Stephen Young, the 17-person student rec board, which was formed to come up with facility fees and usage and access policies, locked out the community.

"They were pretty tight on everything," Young says. "They instituted fees to faculty, staff and alumni, and said no community or spouse memberships. I think that because they were so used to being crowded in shared facilities, they felt that if they left the door open to too many people, the next thing they'd know is they'd be crowded in the new facility."

The University of Southern California opened a student rec center in 1989 that is off-limits to community members, but the rec department has long recognized the need to involve the community in its programs. For one thing, they're "really hurting for space," says Don Ludwig, USC's rec director, and are hoping they'll be able to use some new fields the city is building across the street. "Obviously, city and youth programs will get first priority, but we might be able to tap into that source," he says.

But they also view sharing as a responsibility, and do joint programming wherever possible. USC hosts some L.A. Watts Games and Inner City Games contests, Big Brothers events, inner-city tennis lessons and swim programs. "Our number-one priority is drop-in rec, free play, for students of the university," Ludwig says. "We do what we can to work with the community, particularly those who live near the university who are really deprived, but it's a balancing act."

Most urban-university rec directors downplay the notion that community usage means added security measures. Young notes that the new Temple rec center's security-conscious design is the standard in all rec centers built in the last 15 years. "It's pretty much as it is elsewhere," he says. "Here it's just more important that it work."

Ludwig agrees. "We have had some problems with theft and vandalism, but it could be students, too," he says.

The perception of schools in urban environments being surrounded by danger is a hard one to shake, says Irvin Reid, president of Detroit's Wayne State University.

"There's a perception of this being a high-crime area, but the crime statistics around Wayne are remarkably lower than what your expectation would be," Reid says. "The fact of the matter is you can become a partner with your neighbors quite easily so long as you provide for security and rules by which they must behave. And that's also true for our own students."

Reid, who is in his third month at Wayne State, is an old hand at community partnerships. At Montclair State College in New Jersey, he was instrumental in the construction of Yogi Berra Stadium and the Floyd Hall ice rink, two public-private partnerships involving Montclair residents Berra (baseball hall-of-famer) and Hall (CEO of Kmart) that resulted in a profit-sharing deal that benefited all the parties. "It was the ideal partnership, not for the type of wellness center we want to build at Wayne, but the principle is the same," says Reid.

What he has in mind for Wayne State, and what his team of consultants will be working to formulate into an actual campus master plan, is a new health and wellness center to be placed "wherever the heaviest flow of traffic is," he says, between the main parking garage, the library or classroom buildings. He'd like to see athletic and recreation facilities consolidated somehow in this central location. Reid faces many challenges - existing facilities are currently across a freeway from the rest of the campus, and there's currently no funding for such a project. But calling the new president an optimist would be a spectacular understatement. (While others at Wayne view a dedicated center for recreation as a first for the campus of 31,000 students, "I would look at it," Reid says, "as enhancing what we already have here.")

Not surprisingly, then, Reid downplays the challenges involved in dropping a new campus rec center into an inner-city campus.

"There are always challenges when you have to spend money for facilities and there are so many competing demands," Reid says. "But I don't think they're any different in an urban setting than they are in any other setting."

Along with interviewing consultants and meeting with alumni ("I've got to tell them how I intend to pay for it"), Reid is exploring opportunities for partnerships and reports there has already been interest from potential partners. The likelihood is that state money won't be a large (or any) part of the equation, putting creativity at a premium.

One thing Wayne State has going for it is a president who doesn't need to be convinced of the need for recreational facilities.

"My long-term goal is to provide recreational opportunities for students, many of whom are commuters, so they will get a more holistic education and not a limited one," Reid says. "Anything that will help facilitate that goal, I'm willing to consider."

Holistic, it is suggested, is not a word normally associated with college presidents, but rather, the health-club realm.

"Well, that's what we do," Reid responds. "How much of your college education took place in the classroom? I'll answer it for you - at most, 20 percent. The rest of the time, you had to learn to take care of your body and your mind, you had to learn to stimulate yourself, how to interact with other people - all of those things are a part of holistic learning.

"The question is, where can we have the maximum impact?" he adds. "I think that life sports are much more important to the academic enterprise than the competitive sports we see on television. They affect many more people."