Competing with players recruited abroad requires solid knowledge of the NCAA's foreign policies

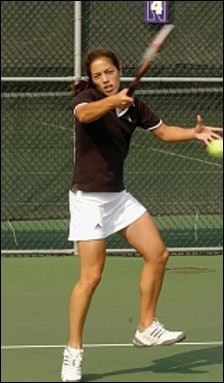

The news handcuffed the Northwestern University women's tennis program like a 120-mile-per-hour serve. Cristelle Grier, whose 25-0 singles record had helped earn her Big Ten freshman- and player-of-the-year honors, would not be allowed to compete for NU in the 2003 NCAA team championships. Deemed ineligible on the eve of the tournament's May 19 first round because (the NCAA surmised) she had not entered college within one year of completing high school, Grier watched as the No. 16 Wildcats were stunned by No. 45 Kansas State. Foreign-born Petra Sedlmajerova (Czech Republic) capped a sweep of the singles matches for KSU.

Grier, too, is foreign, and therein lay Northwestern's problem. The manner in which Grier's native Great Britain passes students through high school is different than the standard four-year matriculation in the United States. Britons, who can begin high school as pre-teens, must decide at age 16 to graduate or take another level of college preparatory courses. Grier and English teammate Ruth Barnes, who also was forced to sit out the KSU match, had chosen the latter. In fact, neither would have been admitted to Northwestern without the additional two years of study.

Among the first of several schools in the 64-team NCAA field to learn of similar infractions involving their English players (in all, more than 50 athletes were affected), Northwestern had a week to appeal the case of the ninth-ranked Grier, who risked not being able to play in the individual bracket, either. The NCAA reinstated Grier, who reached the singles tournament's quarterfinals. But the so-called "tennis rule" - designed to keep English players from coming to the United States to play collegiate tennis in their 20s after exhausting all hope of turning professional - remains intact.

Such is the compliance minefield facing athletic departments whose teams welcome or actively recruit foreign-born student-athletes. And while the Intercollegiate Tennis Association reports that 30 percent of all players competing in Division I last season were of international descent, the potential pitfalls aren't limited to that sport. The number of international Division I men's basketball players has nearly tripled over the past 10 years, from 135 to 392, and now represents 9 percent of the talent pool.

This summer, the University of Hawaii found itself defending its 2002 men's volleyball national championship - but not on the court. In May, the NCAA notified UH of a potential eligibility problem regarding one of its players. The university's own subsequent investigation, concluded in June, affirmed that a player (one of six international players on the Rainbows' 2002 roster) had competed professionally prior to enrolling at UH, a clear violation of the NCAA's amateurism rules. "Although the university's report to the NCAA concludes there has been a violation, it also states that the university and the men's volleyball coaching staff did not know and could not have known about it until the investigation was completed," UH athletic director Herman Frazier wrote in a statement released July 9.

As of this writing, the fate of the Rainbows' championship - the only men's national title in UH history - was still unclear. (The NCAA declined to answer AB's questions about this case, or that of Northwestern.) What has become abundantly clear is the need for compliance officers nationwide to brush up on the NCAA's foreign policies, which have garnered a greater presence in association rule books in recent years.

"The biggest concern when dealing with international students is amateurism, because there are so many professional opportunities out there," says Maureen Harty, director of compliance at Northwestern, where roughly 5 percent of all student-athletes hail from outside the United States. "They don't compete at the high school level like we do in the states. They compete in club programs, and it becomes a matter of trying to determine if those club programs are for professionals or amateurs."

Merely playing among professionals is enough to cause eligibility problems for an athlete, even if he or she never collected pay to play on a certain team or in a certain league. Eligibility is complicated enough when dealing with American student-athletes, but it can be particularly challenging logistically when recruiting student-athletes abroad. "There's a lot of paperwork and communicating with individuals in a different language to ensure that that individual will be considered an amateur by NCAA standards," Harty says.

Though it didn't address amateurism directly, Northwestern's tennis situation served to illustrate that no eligibility detail can be overlooked. Harty, as well as the NU admissions office, understood the graduation dates of Grier and Barnes to be those corresponding with their completion of the extended course track. The NCAA saw the pair as having graduated at 15, then essentially waiting two years before enrolling at NU, a violation of the tennis rule. "These students did take the regular academic program that's needed to get into Northwestern, but the NCAA looked at it differently," says Harty.

"The problem arose because the NCAA set a minimum of qualifications to play Division I tennis for athletes coming out of Britain, but then applied that as the maximum, as well," says Northwestern women's tennis coach Claire Pollard, who is British.

"We went in front of a couple of committees that couldn't really understand the logic behind the initial ruling. It was just one of those unfortunate things that no one felt good about. Life's not really fair. You deal with it and go on."

How the NCAA will deal with this particular eligibility issue in the long term is, again, uncertain. "The rule that says you must enroll within one year has not changed," Harty says. "They are trying to come up with an exact date of graduation for individuals in the British system or similar systems."

Pollard, who led Northwestern to Big Ten titles in each of her first four seasons at the school and envisioned her 2002-03 team at least reaching the NCAA's Sweet 16, had as much reason to feel bad about the mix-up as anyone. And though she credits the NCAA for promptly reinstating Grier, she nonetheless sees cracks in the system. "I can totally understand that it's almost like the English people have their cake and eat it," she says. "To be eligible to play Division I, all you've got to do is finish through the age of 15, and then you can play at certain schools. But you can't play at all schools. These kids shouldn't be penalized for staying on and bettering their opportunities."

Foreign-born athletes are infiltrating Major League Baseball and the NBA at a pace that has many observers concerned. But within our nation's academic institutions, where cultural diversity has long been valued as part of the overall educational experience, international student-athletes are increasingly embraced - and for many positive reasons.

With four international players fortifying a lineup of five, Duke University won the 2002 NCAA women's golf title. "We've had a great time with our foreigners," the team's coach, Dan Brooks, told The Chronicle student newspaper. "They bring a lot to our team in terms of golf, but it's also been a great source of humor with the different cultural and language combinations. It's been a wonderful experience."

For Harty, the benefits of integrating rosters with international student-athletes outweigh the extra effort required of compliance officers to stir the melting pot. "We have basketball players in the United States who are making verbal commitments during their sophomore year of high school, and whether that's right or wrong is another story," she says. "But foreign prospects are generally a little farther behind in the recruitment process. A lot of times, those kids are still available during their senior year. They're valuable to your program - and they add personality and flair. We enjoy having the foreign students as part of our program, just as the university does as a whole."