Intramural program administrators turn to offbeat activities

Monday: Basketball. Tuesday: Basketball. Wednesday: Basketball. Thursday … Volleyball.

The excitement is palpable, isn't it?

For many intramural participants, it doesn't get any more exciting than the chance to shoot hoops at every opportunity. But for other members of the college community, the ubiquitousness of basketball - the squeal of sneakers on hardwood, the trash talking, the smell - can be a major impediment to getting involved in the program.

And for program administrators?

"A lot of people on the programming side," pronounces Shelley Waldman, director of recreational sports at the University of California-San Francisco, "are tired of running the same old thing."

So the search begins for something different. Ideas come with new staff members when they switch jobs, from a university's students or even prospective students, from the compilers of sports guidelines at the National Intramural-Recreational Sports Association (NIRSA), and even from some more improbable sources. Back in the late 1980s, Mississippi State University began playing melonball, a kind of volleyball game played on a tennis court that at the time was appearing in print advertisements for Midori melon liqueur.

"Some desperate types in the recreational sports department said to themselves, 'This looks like fun; we don't need the liquor, but this is something we could play,' " says Laura Walling, MSU's director of recreational sports. "We introduced it to the student affairs staff, and they loved it because it was of a slow enough pace that people of advanced age could play. It was such a huge hit, we tried it next in the intramural program."

This, it is observed, does not seem to qualify as an act of desperation.

" 'Desperate' means we'll take anything from anybody, without much shame," Walling says. "We'll do anything to find something new and different."

Just as oddball sports can come from anywhere, they can be played anywhere. Part of the reason they're played everywhere is that all types of fields and courts experience downtime in which another activity could conceivably take place. That's how tennis courts end up hosting melonball, how racquetball courts become the location for wallyball, how rinks become a preferred site for box lacrosse matches and how sand volleyball courts become mud volleyball courts.

But a high percentage of lesser-known activities are created to utilize gymnasium space in particular, which when unused represents a great big black hole on a rec center's floor plan. It is, after all, not uncommon to see exercisers utilizing 20 square feet apiece in the crowded fitness center, while next door six guys share the main basketball court's 6,500 square feet.

Because NIRSA oversees national intramural competitions, it has a vested interest in seeing that various schools play sports by the same set of rules. Accordingly, the association publishes a Co-Recreational Sports Rule Book covering nine sports - basketball, innertube basketball, innertube water polo, soccer, mini-indoor soccer, softball, ultimate disc, volleyball and wallyball. In addition, a quick check of its web site finds a fairly extensive list of lesser-played activities for which the association has compiled rules (or guidelines, as it prefers to call them). These include a number of basketball-related activities (1-on-1 basketball, 3-point shooting contest, hoop shoot, horse and Nerf hoops) and other pastimes that can take place within the confines of a standard basketball court (indoor flag football, dodgeball, floor hockey, broomball and warball).

The inclusion of some of these suggests how quickly an oddball sport can become part of the mainstream. Kickball and dodgeball, for example, are playground sports that are enjoying a renaissance among adults who now play in leagues run by municipal recreation departments from coast to coast. Broomball and floor hockey, longtime pastimes in northern-tier schools where hockey is popular, have caught on elsewhere. Flag football, an outdoor game that for years was associated with junior-high and high schools' physical education departments, is now an outdoor and indoor game played by a very high percentage of college rec departments. And Wiffleball is a backyard game that has emerged as one of the most popular indoor intramural activities.

The sharp-eyed observer will note that Wiffleball is no generic pastime, but a trademark of the company that has long manufactured and marketed plastic bats and balls for use when playing the game. Trademarked sports turn up on NIRSA's list from time to time, a byproduct of the association's associate membership option. While NIRSA's Mary Callender says the organization has not in the past and won't in the future actively promote, for example, Wallyball, Pickleball or Quickball, associate-member originators of sports have access to the NIRSA database for sending out mailings urging NIRSA members to introduce the sport on their campuses.

Campus rec administrators say they're willing, even eager, to be sold on new activities. In fact, only concern for the safety of participants or the condition of their facilities would prevent them from trying a sport. The former, for example, is what has prevented UC-San Francisco from giving dodgeball a try; the latter has so far kept Denny Byrne, director of campus recreation at the University of New Hampshire, from bringing box lacrosse - a sport in his program during an earlier career stop at SUNY-Cortland - to the UNH gym.

"As with floor hockey and indoor soccer, you've really got to have an indestructible facility," Byrne says. "It's brutal on the equipment. You've got to have a way to buffer the gym, and curtains won't do it."

It's these sorts of concerns that sometimes dictate a sport's final form, no matter what NIRSA's guidelines say. As Byrne notes, "You can always temper the rules. You can run a coed version of the sport, or in the case of floor hockey or box lacrosse, eliminate or limit the amount of checking allowed. Another option is to replace a hard lacrosse ball with a tennis ball. And some people play floor sports with smaller teams because of the size of the gym. You don't want to kill anybody."

By their nature, oddball sports - which are often hybrids of two or more sports, or bastardized versions of more well-known sports - invite that kind of tweaking. Beyond even what NIRSA is tracking, here's a sampling of some lesser-known activities that recreation administrators can try.

• Box Lacrosse. It has already garnered a couple of mentions in this story … but what the heck is it? Played on a rink without the ice, a gym floor with or without a movable dasher-board system, or a multipurpose activity court, it's an indoor version of field lacrosse developed in Canada and popular there and in the far Northeast. There are three significant differences: box lacrosse is typically played with a shot clock, the goals are 4 by 4 feet rather than 6 by 6 feet, and all players are forwards.

• Melonball. As previously noted, it's volleyball played on a tennis court. However, there's no volleying: a legal shot must bounce once before being returned by a player.

• Quickball. A trademarked game, it's a lot like Wiffleball that uses, in the place of a catcher, an "AutoUmp," a cardboard umpire on which is marked the strike zone. The AutoUmp also includes a small, netted hole within the strike zone - pitches coming to rest in the net represent an automatic out.

• Pickleball. Another trademarked game, this one is similar to the paddleball seen on the nation's beaches, but played on a court the size of that used for doubles badminton.

• Flickerball. This sport is best described as ultimate disc played indoors with a Nerf football. As in ultimate disc, the ball can only be advanced by passing it to a teammate. Played most notably at the U.S. Marine and Air Force Academies, it is also played at Mississippi State University and, beginning this month, at Florida State University.

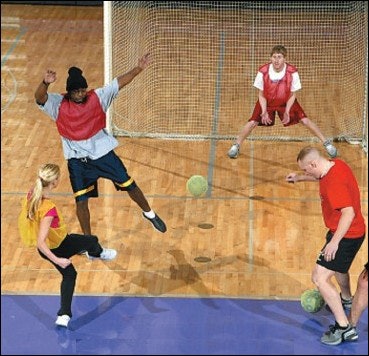

• Tower Ball. Invented by UC-San Francisco's Alan Tower back in the early 1980s, tower ball is a four-on-four non-contact sport, similar to ultimate disc, that's played indoors with a playground ball.

• Uni-Hock. A popular game in the United Kingdom, it's basically floor hockey with plastic sticks, played on this side of the Atlantic at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

• Two-Ball Indoor Soccer. Apparently developed at Oklahoma State University (though it has been on hiatus the past two years while OSU's Colvin Center undergoes a major renovation), two-ball indoor soccer has also been played at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater for the past four years. Play begins with a ball placed in each goal, as each team goes on offense (and defense) simultaneously. Play continues without interruption for two 18-minute halfs. (As in indoor soccer, the dashers or gym walls are in play.) Two referees keep a tally of fouls for each team, and at the end of each half, teams take their allotted penalty shots.

Interestingly, says Larry Mellinger, coordinator of intramurals at UW-Whitewater, outdoor soccer isn't that big on campus. Last year, there were 12 outdoor teams and 18 two-ball indoor teams. "It has grown every year to about triple the number of teams since I got here," says Mellinger. "The kids really enjoy it. That and indoor flag football are probably our fastest-growing sports on campus."

• Four Square, Boxball and Capture the Flag. Dodgeball and kickball are back, so why not these other playground favorites? In one of four square's many variants, players kick-volley a soccer-sized ball from square to square. Boxball is a soccer/football hybrid in which a ball must be kicked if it is on the ground, but can be passed if caught on the fly.

UC-San Francisco's Waldman plans to offer capture the flag, meanwhile, with a number of possible twists. "We may give players a certain time limit, or give them a certain amount of points if they get somebody out of jail or capture the flag," Waldman says. "We might substitute different objects for the flag, like a heavy medicine ball that's more difficult to capture."

• Futsal and Footbag. Two activities that offer opportunities for soccer players to hone their dribbling skills, futsal (a Brazilian form of indoor soccer) is offered at UC-San Francisco, as is "footbag club" (Hacky Sack is trademarked), in which moves are choreographed to music and with various props.

• Goal Ball and Pillow Polo. "Oddball" is perhaps an unfortunate term to use to describe any adapted sports, which are versions of sport developed for play by people with disabilities. However, these two deserve a mention here as activities that both disabled and able-bodied participants can play together.

Goal ball is a sport designed for blind athletes in which a basketball-sized hollow ball containing bells is rolled across goal lines "marked" by contrasting sounds. Legally blind and fully sighted players compete wearing blindfolds. Pillow polo (as offered by, among others, the Anchorage School District's adapted physical education department) is a floor hockey variant in which players on scooter boards strike a volleyball (or multiple volleyballs) with a short hockey stick.

The most well-known adapted sport, wheelchair basketball, is offered by just a handful of institutions. UW-Whitewater, which boasts a large disabled population, offers this sport to both disabled and able-bodied players, for which it keeps about 30 wheelchairs on hand for those who don't have their own.

• Hooverball. The infamous hybrid of tennis, volleyball and medicine ball (played outdoors with a six-pound medicine ball and an 8-foot-high volleyball net), hooverball was developed by White House physician Joel T. Boone to keep then-President Herbert Hoover physically fit. Played by the President, Supreme Court justices, Cabinet members and other high government officials for four years, it disappeared from the national radar in 1933, although The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library Association runs a championship tournament in West Branch, Iowa, every August. "A couple of college students and teachers have asked us for a rules booklet, but I'm not aware of it being played in any intramural programs," says the association's Kathy Grace. "I wish I were aware of some, because that would be awesome."

Two activities for which NIRSA does offer guidelines - spades and sports trivia - show the mainstreaming of passive sports within the college recreation program, a category that would also include fantasy sports and nutrition education. Though they sound like unlikely intramural program offerings, these and other passive activities are advancing in college recreation departments as administrators seek ways to get the non-athletically inclined involved.

"We want to encourage participation in sports of all kinds," says Mark Crager, FSU's intramurals director, and to that end his department offers 51 activities including go-cart time trials, fantasy sports and March Madness contests (winners receive T-shirts), and sports trivia contests complete with game software, buzzers and a scoreboard. FSU campus rec has also held spades tournaments, taken students bowling and rented out miniature golf parks. "We carry the same philosophy as student activities - we want to get everybody active," Crager says. "We're here to provide relief for students, to help them get away from their daily stresses."

Would that program administrators themselves were immune to the stress of watching their new and different activities fail to catch on. Unfortunately, one of the most significant differences between say, flickerball and basketball, is that basketball's rules are widely known and do not require being retaught every semester. Says NIRSA's Callender, "It's really hard to get nontraditional sports to take hold, unless you establish one in a season when there's nothing else going on. It's a lot of work."

Many administrators can attest to the hard-work aspect. Waldman, though she reports with some sadness the gradual disappearance of tower ball, says there's a limit to what she can do about it.

"Educating people who want to play is an awful lot of work for the administration, and I'm the only full-time person in the department," she says. "You can put the word out there and get so many people to play, but once your vets who played all the time leave, if you don't get any new blood in there, it's going to go away."

Tower ball was at one time popular enough at UC-San Francisco to have a league with two divisions, but Waldman eventually combined the advanced and beginner divisions in the hopes that the advanced players could teach the beginners how to play. When the numbers fell to four teams, it was dropped as a league sport, and Waldman is now helping a third year medical student who wants to revive tower ball to run it as a semi-regular drop-in activity.

"Last Monday we had eight people play; this past week we had 10," Waldman says. "I told the players that if they could get their numbers to 16 to 20 consistently, we'll have a league next season. We'll see what happens." The plan is to schedule an end-of-semester "tower ball extravaganza," complete with food and drinks, to bring in more potential players.

Program administrators sometimes assume that the popularity of a traditional sport will drive participation in the sport's nontraditional twin. Soccer players, for example, may flock to indoor soccer venues come winter - but then again, they may not. Tony Dilts, director of intramural sports and recreation at Western Michigan University, is still surprised that his hockey-loving campus in the hockey-loving Upper Midwest, which avidly supports intramural arena football, doesn't get enthused about broomball. "It's pretty big in some schools, and you'd think that for people who don't have the skills to play regular hockey this would be a way to play a form of hockey," Dilts says. "But we just can't get a league going."

One method Florida State University and other intramural programs use to drive participation is to make new activities "point sports," meaning that teams join up in the hopes of scoring the points they need to secure the overall campus championship at the end of the year. Still, Crager says, "It can be a hard sell. I think it takes a minimum of a couple of years. We usually try a new activity for one year, see what kind of numbers we get. If it doesn't grow, it's gone."

Trying new things, tinkering with the mix, pushing the activity envelope - these are now constants in the field of college recreation. As UNH's Byrne points out, creativity in programming goes well beyond giving a handful of freshmen something to do on Thursday afternoons.

"We have to pull out all the stops for budgetary reasons, for public-relations reasons, for educational reasons, even for recruiting reasons," he says. "Many of us in campus rec and sports clubs aren't used to thinking in terms of recruiting, but we do now. We have to be as creative as we can, because that leads to more people coming in, more interest and more financial support - because, you know, the biggest sellers of the recreational program aren't us. We go in and answer questions, but the students are the ones selling the recreational program.

"Besides," Byrne concludes, "I think it's fun to try stuff."