An injured climbing student gets an education on waivers and the law

Considering how extensive the use of waivers is among athletic, recreation and fitness program administrators, it is amazing that so much confusion still surrounds their legal value and the protection they can provide.

A waiver is, in fact, a simple contract. In it, the user of a recreational service agrees to relinquish his or her legal right to sue the service provider in the event that the user is injured as a result of the provider's negligence. In exchange for giving up his or her legal right to sue the service provider, the provider agrees to allow the individual to utilize its services and facilities.

To ensure that the courts will uphold a waiver, it is important that the service provider consider the following items when writing a waiver:

• Does the waiver use clear, easy-to-understand language? • Is the document clearly labeled a "Waiver"? • Does the document fill just one page? • Does the document specify the word "negligence"? • Does the document refrain from the use of fraudulent statements? • Did the person signing the waiver actually read it, and does the document specify this requirement? • Does the document contain any indemnification language?

Although some of these might not be required by every court, it is better to be safe than sorry.

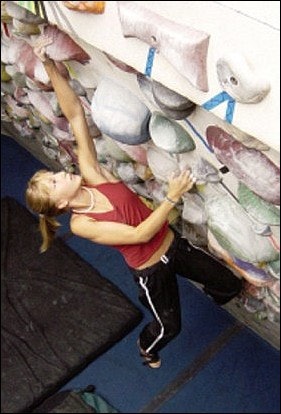

One example of how important waivers can be to recreation or fitness service providers is Lemoine v. Cornell University [769 N.Y.S.2d 313 (2003)]. In this case, a student at Cornell University, Nadine Lemoine, enrolled in a seven-week basic rock-climbing course offered by Cornell's outdoor education program. Before the class was allowed on the school's climbing wall, Lemoine and the other members of the class not only were required to watch an orientation video describing safety procedures, but were also required to sign a release holding Cornell harmless from liability for any injuries caused by use of the climbing wall, including those caused by Cornell's own negligence.

In addition, Cornell also required Lemoine and the other members of the class to sign a "Contract to Follow Lindseth Climbing Wall Safety Policies." In that contract, Lemoine promised that she would not climb above the yellow "bouldering" line without the required safety equipment.

During her first class, Lemoine, who was not wearing safety equipment, was climbing with most of her body above the bouldering line. As she descended the wall, one of her instructors told her where to place her hands and feet; there were 10 other students under the supervision of two instructors. Lemoine claimed that while descending she lost her footing and fell to the floor below, which she described as virtually unpadded. Cornell, however, disputed this claim and, pointing to the incident report form, claimed that Lemoine decided to jump off the wall. The instructors asserted that the floor was padded and Lemoine was 4 feet from the ground at the time that she left the wall.

Lemoine, who broke her wrist in the fall, filed a lawsuit against Cornell asserting negligence and gross negligence. The case was dismissed by the trial court, which held that the release and safety contract Lemoine signed barred her from recovering any damages she may have suffered as a result of Cornell's negligence. On appeal to the New York Appellate Court, Lemoine argued that the release and safety contract went against public policy and therefore should be held void.

In support of this position, Lemoine pointed to Section 5-326 of New York's General Obligation Law, which states in part:

Every convenant, agreement or understanding in or in connection with, or collateral to, any contract, membership application, ticket of admission or similar writing, entered into between the owner or operator of any pool, gymnasium, place of amusement or recreation, or similar establishment and the user of such facilities, pursuant to which such owner or operator receives a fee or other compensation for the use of such facilities, which exempts the said owner or operator from liability for damages caused by or resulting from the negligence of the owner, operator or person in charge of such establishment, or their agents, servants or employees, shall be deemed to be void as against public policy and wholly unenforceable.

In rejecting this argument, the court held that the legislative intent of Section 5-326 was to prevent amusement parks and recreational facilities from enforcing exculpatory clauses printed on admission tickets or membership applications because the public is either unaware of them or not cognizant of their effect. The statute, the court concluded, was enacted to cover places of "amusement or recreation," not facilities that are used for "instruction and training."

In assessing whether a facility or service is instructional or recreational, courts have examined a variety of factors, such as the organization's name, its certificate of incorporation, its statement of purpose and whether the money it charges is tuition or a fee for use of the facility. The question of whether a facility is used for instructional or recreational purposes is much more difficult, however, in situations where a person is injured at a mixed-use facility (one that provides both recreation and instruction).

For example, some New York courts have found that Section 5-326 voids the particular release where the facility provides instruction only as an ancillary function, even though it is a situation where the injury occurs while receiving some instruction (as in Bacchiocchi v. Ranch Parachute Club, 273 A.D.2d 173, 710 N.Y.S.2d 54 [2000]). Other courts, however, have focused less on a facility's ostensible purpose and more on whether the person was at the facility for the purpose of receiving instruction (for example, Scrivener v. Sky's the Limit, 68 F. Supp. 2d 277, 281 [1999]).

In Lemoine's case, the plaintiff pointed out that her enrollment in the class entitled her to a discounted fee in the event that she sought use of the climbing wall on nonclass days and that, additionally, Cornell allowed its students, alumni and graduates of the rock-climbing course to use the wall as long as they paid the regular fee and watched the safety video. Therefore, Lemoine argued that since the facility was both recreational and instructional, Section 5-326 must apply. While acknowledging that Cornell's facility is a mixed-use one, the court held that it was unquestionable that Cornell was an educational institution, and that the purpose of the climbing course and facility was for education and training in the sport of rock climbing. In addition, the court found that by focusing primarily on Lemoine's purpose at the facility, it was indisputable that she paid tuition (not a fee) for lessons and was injured during one of her instructional periods. Therefore, the court concluded, the statute did not apply.

Having found that the release and safety contract were not void by the statute, the court next examined whether the release and safety contract were valid. In concluding that they were legally enforceable, the court found that the release unambiguously acknowledged the inherent risks of rock climbing and the use of the climbing wall, including the risk of injury from falling off the wall onto the floor below. Since Lemoine initialed and signed these documents, the court ruled that the waiver was valid and that the trial court acted properly when it dismissed Lemoine's lawsuit.

Lastly, the court rejected Lemoine's allegation of gross negligence (reckless conduct that borders on intentional wrongdoing). Even assuming that everything Lemoine claimed was true, the court found that there was no evidence of gross negligence on the part of Cornell.

Although Lemoine lost her lawsuit, there are a couple of things that should be pointed out. First, while Lemoine was unable to apply New York's General Obligation Law in this case, in most cases involving waivers in the area of recreation services, Section 5-326 of the law will prevent service providers from enforcing such exculpatory agreements.

Second, as the court pointed out in Lemoine, waivers only protect service providers from liability for ordinary negligence. If the service provider or its employees are grossly negligent or reckless, the waiver will not protect the provider.