Medical researchers hope to shed new light on concussions.

The helmet-to-helmet collision occurred during the opening kickoff of a mid-September football game between two Wisconsin schools, Pewaukee High and Watertown Luther Prep. Even though one player, a Pewaukee senior, suffered a mild concussion, the hit that gave him temporary memory loss could positively impact high school football players across the country.

The injured specialteams player was part of a study that tracked head injuries to football players at 13 southeastern Wisconsin high schools during the 2000 season.

By using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a new technology sensitive to changes in brain activity, two Milwaukee-area doctors hoped to find out for the first time what happens at a physiological level both after a concussion and during recovery.

And if they can determine that, they just might help reduce the number of recurrent concussions in athletes at all levels nationwide. "Your risk for injury increases significantly if you have a prior history of concussions," says Michael McCrea, head of neuropsychology services at Waukesha Memorial Hospital and one of the two doctors helming the study, funded in part by the National Federation of State High School Associations. "At the neuropsychological level-the brain level-we still have not discovered how long it takes to recover.

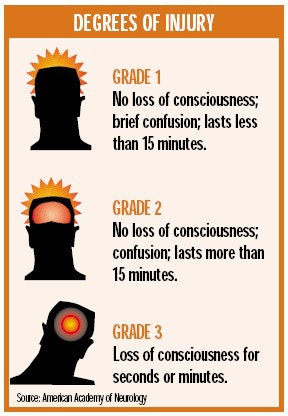

Our hope is to clarify what the neuropsychological effects of sports concussions are and what the period of recovery is." The results, which won't be available until next year, also will provide more insight into when it's safe for a player to return to the field, McCrea says. Guidelines issued by the American Academy of Neurology recommend that athletes not return to play until anywhere from 15 minutes to one month or longer after concussion symptoms subside, depending on the severity of the injury. Concussion symptoms include inattention and incoherent thought processes.

The injured Pewaukee senior underwent a series of cognitive tests the night of his injury based on the Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC), a sideline process developed for non-medical personnel to measure a player's orientation, immediate memory, concentration and delayed recall. The next day, he received a free fMRI and consultation with McCrea that helped gauge the impact of the injury on his brain, and he met with Pewaukee's athletic trainer, Marnie Brown, early the following week to evaluate his symptoms. The SAC test was administered again seven days after the injury to further track his progress, and the player was expected to undergo another fMRI 60 days after the injury.

An estimated 63,000 cases of mild traumatic brain injury affect high school varsity student-athletes each year, according to a September 1999 report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association and based on a study of participants in 10 sports from 246 schools. Football injuries account for about 63 percent of those cases.

In most instances, McCrea says, concussion recovery occurs within a couple of days with no detectable damage to brain structure. Debate continues, however, about the length of time it takes to fully recover from a concussion and how long a player should remain sidelined after displaying a prolonged lack of symptoms. "There is one general guideline that all experts agree on in the management of sports-related concussions," McCrea says. "No player who is reporting or exhibiting any post-concussive symptoms should be returned to competition."

At least some of the answers to other concussion-related questions could lie within McCrea's current research. While a conventional MRI determines the brain's structural damage, an fMRI monitors functional changes in the brain, such as cerebral blood flow that indicates variations in brain activation as a result of a concussion. McCrea and Thomas Hammeke, a neurology specialist at the Medical College of Wisconsin, hope to determine whether a concussion's effect on the brain lingers beyond the disappearance of outward symptoms. Such a determination could help prevent Second Impact Syndrome, caused when a player suffers a second concussion (often from very light impact) while still recovering from an earlier concussion. While rare, Second Impact Syndrome can be permanently disabling or fatal.

Of the 600 or so players involved in the study, about 30 to 40 were expected to experience some form of concussion-usually a mild, or Grade 1, concussion-over the course of the study. Each player who participated was partnered with a teammate, and each served as a control subject for medical testing in the event his partner got injured.

Brown, an ardent believer in the SAC test, was gung-ho to be part of the fall study. She began using SAC during Pewaukee's 1998-99 high school sports season as a way to help explain to coaches and parents why a particular player who suffered a head injury wasn't allowed to return to action immediately. Before using SAC, Brown says, one multisport student-athlete suffered two concussions playing soccer in the fall, and he was blacking out on the basketball court from "little dings" caused by contact. "Using that example is actually how I sold my athletic director on getting involved with SAC," she says. "Now I know when my kids are doing a lot better, and I know when to be a little bit more concerned."

Getting the support to participate in the most recent study-which required players to undergo extensive tests, answer detailed medical questions and submit to fMRIs-also required a sales pitch. "My AD and I both had to explain and justify it to our administration, parents and coaches," Brown says, adding that Pewaukee's football coaches trust her judgment on when to keep a player out of the game. But she hints that the sell wasn't as easy for her colleagues at other schools involved in the study. "We need coaches' support in order to administer this study properly and effectively," Brown says.

Even though the current study has concluded, McCrea hopes to extend its principles to more schools and more sports-including soccer, wrestling and hockey. Any new information or spinoff concussion research that results from the McCrea/Hammeke study will likely be welcomed. With coaches and administrators increasingly becoming the target of lawsuits stemming from concussion injuries, finding ways to prevent crippling or even fatal head injuries is an even greater priority than before.