A Utah tax commission questions municipal government's role as a fitness provider

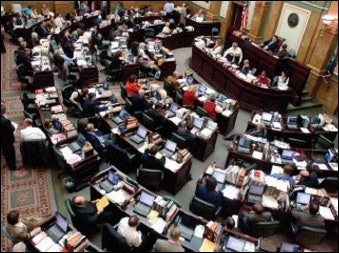

The Utah Recreation and Park Association's Oct. 10 public hearing before the state Tax Review Commission wasn't as much an inquisition as it was an opportunity to clear the air. The point of contention - whether municipal recreation centers should pay the same taxes as private fitness centers - had initially been raised in the State Legislature's chambers during the 2002 general session. Back then, owners of two health club chains alleged unfair competition and successfully lobbied state senators to push through the Legislature a joint resolution authorizing an intensive review of the tax-exempt status of public rec centers. By October's meeting, 20 months had passed, during which the clubs' claims had gone largely unchallenged.

At the hearing, the Tax Review Commission - an advisory board responsible for submitting to the Legislature recommendations regarding tax laws - heard testimony from representatives of both public and private interests. Speaking on behalf of parks and recreation agencies were Steve Carpenter, URPA's executive director, and Roger Tew, URPA's attorney and a legislative lobbyist with the nonprofit Utah League of Cities and Towns. Their argument was simple: Health clubs pushed for the review of tax-exempts not because they were interested in leveling the playing field through fairer taxation. Rather, they wanted to eliminate any impediments - public rec centers, in particular - to their securing market exclusivity for Utah's fitness-conscious consumers.

"The issue is not taxation. If taxes were levied, it wouldn't have anything to do with health clubs' profitability. Whether they're viable or not is based on the niche market they serve," says Tew, who served on the Tax Review Commission before joining the ULCT staff. "The real issues are, What is the proper role of government and what is unfair competition. And more important, who gets to decide the proper role of government?"

They are questions not easily answered, especially as obesity continues to be the main threat to the health of future generations. Whether it's because of pressure from the federal government or their own constituents, more municipalities are feeling compelled to expand their fitness and recreation offerings. And the logical place for residents to access these services, says Carpenter, is a public recreation center. "This is not about quality of life. It's about quality of community," he says. "These facilities serve as the hub of activity for family recreation. Recreating together strengthens family bonds."

But owners of Lifestyles 2000 and Gold's Gym franchises in the Salt Lake City and Ogden areas argue that such facilities, which have multiplied over the past decade, are exceeding the public need and instead more closely represent businesses that compete directly with theirs. Tew disagrees and says that rec centers are simply offering activities that appeal to as many people as possible. "The health clubs are saying, 'We don't have any problem with basketball gyms or swimming pools. What we have a problem with are group-cycling classes and aerobics instructors,' " he says. "But what are parks and rec departments going to say - that 95 percent of the people can use the facility, but if 5 percent want group exercise they have to go to the other side of town to use another facility? That's stupid."

Carpenter argues that because they are the end users, the constituents of each community are ultimately responsible for deciding whether or not to build a recreation center, and if built, what amenities that facility will offer. "Some communities don't want these facilities," he says. "I live in a community that recently voted down a bond referendum for an aquatic center."

And that's OK, says Tew. "My point is that's what democracy is all about. I live in a community that doesn't offer those services. But once the decision's made, that's it. That's the political process."

In many communities nationwide, that process seems to work. Some communities are more supportive of public recreation facilities, others less. But what happens when the expectation becomes that rec centers are as essential to a community as utilities, roads and cultural arts facilities - all of which historically have been viewed as "societal goods," and thus the responsibility of local government? "Most of what government does is a subsidy. I don't know why this activity is being isolated," says Tew of recreation centers. "There's nobody making money on it. People are being paid, yes, but the ownership interest is not driven by profits. At a health club, somebody is in it to make money. Those are fundamentally different motives."

For club owners who feel that fitness and recreation haven't yet attained status as essential government services, Carpenter hesitantly suggests there may be a middle ground for public and private interests. "If we ever had to take one, I guess our fallback position would be to calculate the square footage of our fitness area - out of a 70,000-square-foot facility, it's not going to be much - and let the state tax us on that," he says.

Tew doubts the effectiveness of such a method, besides the fact that making such a concession could leave public rec facilities vulnerable to more troubling demands in the future. For example, club owners could push for taxation of other components that, technically speaking, could also be qualified as fitness areas, such as aerobics rooms and saunas. "How do you segregate so that you pay taxes on one part of the facility and not the other? That would be an enormously expensive undertaking for what would bring in very little money," he says. "It's an easy concept to talk about in the abstract, but when you get into specifics, it's much harder."

Money is the root of almost all disputes. That said, Carpenter came away from October's Tax Review Commission hearing pleased that the dialogue was more education than confrontation. Participants could have easily plunged into a mudslinging debate on the fitness and recreation industry's public-private controversy. Instead, the hearing provided influential state government officials the opportunity to hear both parties' concerns and to discern for themselves the true goals of public parks and recreation. "We're about kids, seniors and everyone in between. We're about healthy communities and working with schools," Carpenter says. "All of this, most health clubs don't want a part of."

Tew saw another positive emerge from the discussion. "At least in Salt Lake County, political people and rec people are coming up with a reasonable master-planning process that will decide what facilities are going to be developed. Thus far, it has been a little ad hoc," he says. "Then you put the private club owners on notice that this is what's going to happen in the community in 10 years, and they can plan for that."

During another hearing on Oct. 24, commissioners were further briefed on the philosophical missions and financial resources of each of Utah's 29 major municipal recreation centers. As winter turns to spring and work on the tax-exempt status review comes to a close, Tew expects even more questions to be raised - which is just fine with him. "I've been advising parks and rec people, 'Rather than fight the study, let's get the issue out there and talk about it,' " he says. "This issue's not going to go away."