As the average club member gets older, so does the average personal trainer.

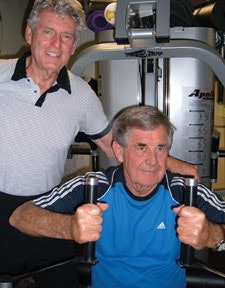

Even though he has 10 years of experience working with older adults, Fitzgerald remains among a relatively new breed in the world of exercise and wellness: The 75-year-old personal trainer. A newcomer to the field at age 65 after a long career in the paper business, Fitzgerald is the natural embodiment of what is almost certain to become a trend as the baby boomers flex their collective muscles. Working as an independent contractor, he gets some of his clients by giving talks at senior centers and other places where older people usually congregate. A typical presentation starts with Fitzgerald asking the crowd how many of them go to their doctor for their health. Arms are raised, a little tentatively, across the room.

"I tell them, 'You're all wrong!' " Fitzgerald says with gusto. " 'Doctors cure illness. You go to the doctor when you're sick. If you want health, you go to a guy like me.' "

Fitzgerald hails from an era when there was more than a little misinformation out there about the benefits of exercise. A self-described "sickly kid," he was nonetheless told by his parents and the family doctor that rest, not exercise, would make him well. "I come from the Dark Ages," he says. "Granted, you go back to 1900 and the life expectancy was 47, but we didn't know that resistance exercise helps your immune system."

He remembers, too, that there was a time when college athletes were kept away from lifting weights; now, he says with a laugh, "You couldn't play ping pong at the college level without them sending you to the weight room." The common wisdom, even with non-athletes, was that lifting weights would damage the joints, leading to all sorts of medical problems as exercisers got older.

In spite of all the negative energy, Fitzgerald made exercise a regular part of his life. He toured as a pro wrestler for a time, and helped spread the gospel of fitness to a variety of high school teams. Eventually, after retirement, he moved to California to be closer to his daughter, got certified as a personal trainer, and began his latest career. He works with some people younger than he and some older (including his three centenarians), but no one too young.

"I could, but I don't," he says. "There are four million trainers who will train those people. Older people really need the help."

Colin Milner, executive director of the International Council on Active Aging, believes that older exercisers tend to prefer the services of someone like Fitzgerald. "To take someone through a workout, it doesn't matter what age you are," Milner says. "But there's a connection that many times older adults won't get from a younger trainer. An older trainer will have a much better understanding of their life stage and of many of the issues that they face, whether related to their health or personal issues like their financial picture."

Richard Derwald, an old buddy of Fitzgerald's from his pro wrestling days, concurs. As the founder and coordinator of the Erie County, N.Y., Senior Fitness Program, Derwald, 73, has tried to match older exercisers (the program counts 40,000 registered participants through the county's 55 senior centers) with exercise mentors of like age, as older personal trainers are in short supply. "With a younger trainer, they feel like they're listening to their granddaughter," Derwald says. "With an older trainer - I tell you, it really gets their attention."

Certainly, an older trainer will help assuage the injury fears of an older person reared on doctors' anti-exercise rhetoric. So says Fred Lipsky, who is five years removed from a back injury that derailed his career with the Suffolk County, N.Y., police force, and is now the owner of Five-O Fitness, a personal training studio for older adults that he runs out of his Remsenburg basement.

"I can understand where they're coming from, how they feel," Lipsky says. "Once you pass 40, your body changes a lot. You're not as flexible and not as strong. From a training standpoint, it's better to have experienced aging than to have learned about it from a book. If you've never experienced it, you have no idea. It's like thinking you know how to run a marathon when all you've experienced is a 5K race."

Data from the International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association indicates that members 55 and older make up the fastest-growing segment of the health club population. Younger personal trainers are taught that these older members are more limited in their physical abilities, and yet everyone of a certain age connected with the industry seems to know a peer who has been injured by an overzealous young trainer - Lipsky's wife (torn rotator cuff), Milner's mom (fell off a treadmill), even Milner (torn rotator cuff). Milner says it's not so much how hard they push their clients - a Tufts University study was the first to suggest that older adults should be trained at the same intensity as younger exercisers - but the techniques used.

"An older trainer has felt the aches and pains associated with age, and won't push them through the range of motion because they don't have the range of motion," Milner says. "Theoretically, a younger trainer should know this."

Even if the trainers don't know it, their older clients do. "Younger people want to look buff, older people want to be able to function," Lipsky says. "They want to be able to get dressed by themselves, lift up their grandkids. They're not looking to be Arnold Schwarzenegger."

Accordingly, Lipsky stops short of pushing his clients to the edge, no matter what the research says. "A lot of people judge a personal trainer on how tough he is," he says. "It's the opposite when you get to an older population. You could exhaust them with a 7-pound dumbbell if you wanted to, but my clients don't walk out of here exhausted."

There's simply no need for that, Fitzgerald says. "The trainers I used to know, they'd get a client and work them hard so that the next day they'd know they'd had a workout," he says. "It was the dumbest thing in the world. Everything should be a challenge, but this idea that took hold years ago, 'No pain, no gain,' is ridiculous. Who would want to come to a place where you're constantly in pain?"

Fitzgerald's clients have included people rehabbing after hip replacements, people nursing decades-long foot problems and, most memorably, a woman with Parkinson's disease who came to him because she wanted to be able to knit again. After five months of workouts, Fitzgerald says, her tremors had abated. "I've seen amazing results in the 10 years I've been doing this," he says. "I'm not bragging, because anybody could do what I do, but out of the thousands of clients I've worked with, everyone has improved their health and their mental status by working out. It's no big mystery. It really works."