![[Photos courtesy of Defense Video Imagery Distribution System]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2016/11/ab.Military1116_feat.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&q=70&w=400)

This article appeared in the November | December issue of Athletic Business. Athletic Business is a free magazine for professionals in the athletic, fitness and recreation industry. Click here to subscribe.

![Branches of the armed forces have moved to incorporate more functional fitness training in recent years. [Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Alora Blosch]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2016/11/ab.military1_sm.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) Branches of the armed forces have moved to incorporate more functional fitness training in recent years. [Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Alora Blosch]

Branches of the armed forces have moved to incorporate more functional fitness training in recent years. [Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Alora Blosch]

The military has a fitness problem. Despite a spate of new fitness initiatives spanning more than a decade, the rate of overweight and obese diagnoses among military personnel has climbed 73 percent over the past five years, according to a 2015 report by the Defense Health Agency. Compared to the national scale, where one-third of U.S. adults are obese, the military's 8 percent overweight figure still hardly seems like a problem, except when we're talking about people whose job success in defending their country depends on being in top physical condition.

The DHA's report, based on data supplied by health providers, attributes some of the increase to greater recognition of weight gain as a medical issue, but also places some blame on national trends. According to the report, "The increase in obesity in the general population has resulted in ... an increase in the number of applicants for military service who are overweight and obese and at risk of being deemed 'medically unfit for service.' "

The military's problems are a symptom of a national epidemic decades in the making, agrees Frank Palkoska, chief of the Army's Physical Fitness Training School. "We have 18- and 19-year-old kids coming into basic training who can't skip or perform a forward roll," he said in an interview last year. "They have not learned the motor patterns to execute these basic movements. It's very difficult to get a person through an obstacle course when they're starting so far behind, and 10 weeks isn't enough to get them up to speed. You acquire most of your basic movement patterns by first grade, and our youths today just aren't getting the physical education time they need."

After years of diversifying programming opportunities across the branches of the armed forces — implementation of high-intensity interval training, functional fitness, virtual fitness programs and expanded facility hours, to name a few — the emphasis is coming back to the fundamentals of physical activity.

BACK-TO-BASICS TRAINING

In 2015, the Army released its first Health of the Force report, an attempt to establish and share health and wellness best practices among its installations. It utilizes data gathered from the Performance Triad — comprised of health, sleep and nutrition data — and creates an installation health index.

The benchmark report found that musculoskeletal injuries account for 76 percent of injuries among soldiers deemed non-deployable. In total, the report says that 55 percent of soldiers receive a musculoskeletal injury each year. By comparison, the rate of such injury among college athletes is just 25 percent.

Some of the injuries are work-related, some result from overtraining, and some manifest because recruits were never taught proper exercise technique. "We're fighting a 100-year tradition of doing fitness incorrectly," says Ron Doiron, health and wellness coordinator for the South Carolina Army National Guard. "The thinking in the military has been, 'If somebody can't do well at physical training, make them do more.' That's the problem. Ninety percent of the problem is due to inefficient, incorrect movement patterns. Motor patterns haven't been developed."

Nearly 20 percent of the South Carolina National Guard's enlisted members are on a heightened leave program due to injury or Army Physical Fitness Test failure, Doiron says. Recognizing the challenges of changing the wellness habits of service members who spend the majority of their days preoccupied by their civilian jobs and lives, the SC National Guard Health and Wellness Program, a sub-directorate of the Service Member and Family Care (SMFC) Program, contracted Doiron and his team through Sharp Business Consulting Services LLC.

The problem is not new, but as it becomes more endemic in the general population, the need to correct it among military members becomes more apparent. "In 1985, I went through basic combat training," Doiron says. "That very first morning, I took the APFT. For the first time in my life, I was expected to accomplish a maximal number of push-ups, sit-ups — all in two minutes — and for the first time in my life, I learned what two miles of running felt like. At the end of that, I was taught nothing about how to do it."

Doiron and his team work closely with clients to educate them in proper running technique, correct push-up form, body posture, and more. "We write a program based on your condition level and your goals," he says. The program is generally only expected to last a couple of weeks, at which time they meet again to see how the soldier has progressed and to develop a new plan. "We're finding that for a lot of the general population in the SCNG, the primary issue with running is technique," Doiron says. "The other issues are endurance and speed."

Beyond assisting those service members in need of relearning the basics, Doiron and his team are also taking a proactive approach with new recruits. "Most of the older soldiers have got their minds set, their routines set, it's hard to create change," he says. "The new recruits don't have a routine. We can help them establish that routine."

Similar programs have been adopted by National Guard units in other states, with a common focus remaining on proper training techniques, nutrition and goal-setting.

The emphasis on individualized coaching is also the basis for programs in the Army and Navy. Approximately 30 Army Wellness Centers have opened around the world as part of the Army's holistic approach to readiness training. Six core programs are meant to look at an individual's overall health and wellbeing, going beyond weight loss to include nutrition, tobacco use, sleep and stress. "Health coaching is probably our biggest benefit," Daryl Stevens, director of the Fort Bliss AWC, told Army Public Affairs this summer. "You sit down with one of the health educators and talk about general wellness, improving your health, decreasing your BMI, meal planning, better sleep habits, activity, etc."

OCCUPATIONAL FITNESS

Long before the military's official announcement last year that it would be opening all combat jobs to women, speculation has swirled around what such a change would mean for the various branches' respective fitness standards. Would women be held to a different standard? The question became part of a broader discussion of fitness standards across the armed forces.

New standards implemented by the Army and Marines set aside the question of male versus female and instead focus on the physical characteristics needed to perform job duties. "Let's take an artillery soldier, for example. An artillery round weighs 75 pounds, and it doesn't care whether you're a man or a woman," Dan Dailey, sergeant major of the Army said in an interview with the Army Times. "You've got to be able to lift that thing and put it inside of the gun ... and you've got to be able to do it over and over and over again."

This is the thinking behind tiered physical performance standards being implemented in the Marines and Army, though the two branches are taking different approaches.

In October, the Army rolled out its incremental fitness assessment. The Occupational Physical Assessment Test, or OPAT, includes four components: a medicine-ball throw, a standing long jump, a deadlift and a shuttle interval run. Rather than pass/fail, soldiers fall into one of four categories based on their performance, and the Army's various occupational specialties have been classified accordingly. Those who meet the standards for the highest category qualify for all occupational specialties, which include combat roles such as infantry, armor or combat engineer, while those who fall into lower categories are eligible for less-demanding jobs.

Rather than lumping together occupations into tiers based on level of fitness required, the Marines last year defined fitness requirements for 29 separate occupational specialties.

The Marines and Army are both revising the standards of their body composition tests. The "tape test" is now waived for Marines who score above a certain threshold on other performance tests, and body composition standards for women have been revised to better reflect the physiological differences between men and women. "I've had a number of females say, 'Thanks for giving us a little more on the body mass,' " Marine Commandant Gen. Robert Nelle told the Marine Corps Times. "One of the things we learned in the Ground Combat Element Integrated Task Force study is that those female Marines who were most successful, they had a larger body mass."

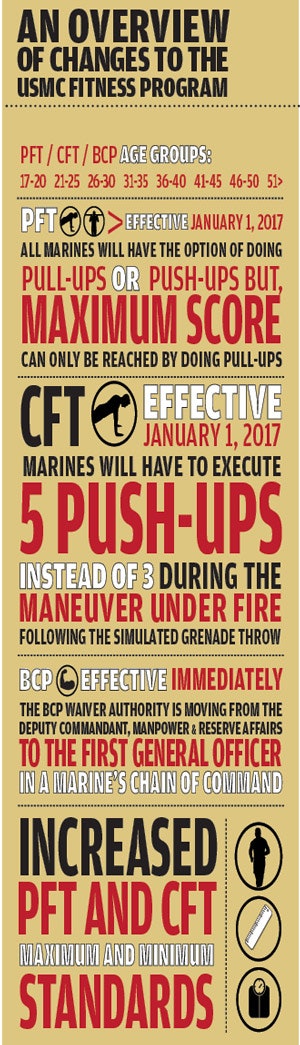

Starting in 2017, the Marines will also be implementing changes to their physical fitness test and combat fitness test. Gone is the flexed-arm hang, replaced by the option to do pull-ups or push-ups, as well as increasing the number of crunches required for a maximum score. These adjustments, as well as others made to the tests, will be monitored and re-evaluated in two years.

Meanwhile, other branches of the armed forces will be watching, as well. The Navy, which implemented relaxed body composition standards last year, has also been mulling the idea of an occupation-based physical performance test, but pragmatic leaders are hesitant to act just yet. "A lot of people say every sailor in the Navy is a firefighter, because you can find yourself on board a ship regardless of your source rating, right?" Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Mike Stevens told Navy Times in January. "When you are on that ship, if a fire broke out, for example, everybody would have to be able to fight it. Maybe your test revolves around something like that."

An instructor for every unit

To improve the fitness of the fittest force, the Marines rolled out a new occupational specialty this fall: the force fitness instructor. In September, the Corps announced that it would be recruiting 50 officers to participate in a new fitness instructor course. The five-week training program would "give a Marine the skills to go back to his unit and be able to design a physical fitness program for his unit and to be able to assess individuals and help that unit implement this [program] to make every Marine and sailor better," Maj. Gen. James Lukeman said in a recent interview.

The ultimate goal is to train 1,000 instructors, or one instructor per 200 Marines. Previous experience is recommended but not required. According to a release, a force fitness instructor "will serve as the commander's subject-matter expert on physical fitness and sports-related injury prevention. This Marine will advise the commander on the design and implementation of a structured, progressive [mission essential task list]-based physical fitness training program that is uniquely tailored to the unit's training and exercise employment plan."

The instructor course will be held six times per year and focus on nutrition, injury prevention and sports medicine.

This article originally appeared in the November / December 2016 issue of Athletic Business with the title "Military fitness: the latest moves to improve the fighting forces"