This article appeared in the September issue of Athletic Business. Athletic Business is a free magazine for professionals in the athletic, fitness and recreation industry. Click here to subscribe.

Thirty-three years ago, Indiana University's natatorium opened as the largest indoor pool in the country and quickly earned a reputation as one of the fastest pools in the world. Three decades later, the fastest pool was still the fastest — but the ceiling leaked, the lighting was inefficient, the locker rooms were outdated and many of the mechanical systems were in need of upgrades.

"Most buildings corrode from the outside — weather, rain and snow," says Tom Morrison, vice president for capital planning at IU. "An aquatics facility gets it from both directions. That inside climate is moist, has chemicals and corrodes more quickly."

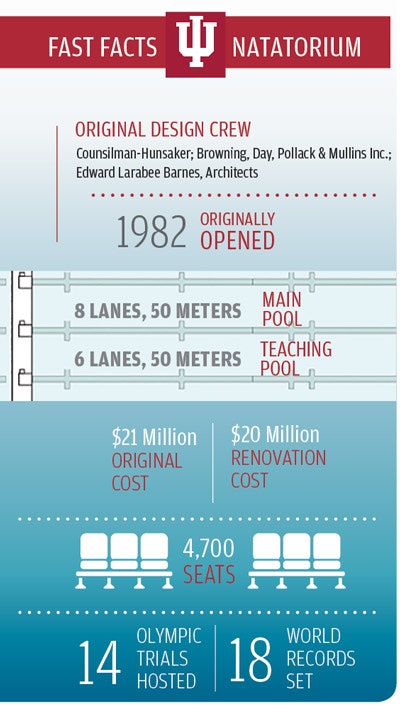

The university was faced with a tough choice. Renovating the 220,000-square-foot facility and its two 50-meter pools would not be easy or inexpensive. "We certainly did look at whether we wanted to keep the facility," Morrison says. "You have to with any process, whether it needs to be demolished, replaced, replaced with something not as large. Not only at the university but in the community — the city of Indianapolis and the state of Indiana — folks stepped forward and said, 'We want to keep the facility as an attraction.' "

Thus kicked off a 21-month, five-phase renovation that would not only preserve IU Natatorium's reputation as the fastest pool in the country but restore the "wow" factor that had faded over the years.

SETTING PRIORITIES

Prior to the major renovation, repairs and changes to the Natatorium had been very minor. "It had the look of an early 1980s building," Morrison says. "It had grown to the point where we had a roof that was leaking and needed to be replaced. The concourses had moisture problems. The infrastructure in terms of plumbing, lighting, HVAC systems — the filtration of the pool had been upgraded, but we could make it more efficient.

"Getting to the point of doing it was the hard part, getting the funding together, the commitments," Morrison continues. "We wouldn't kid anybody to say that a natatorium of this size can make a profit. But it is very valuable to the community and the state, and we wanted to maintain its heritage and reinvigorate it."

To aid in the undertaking, the university enlisted the services of architects involved in the original planning, now working at local Indianapolis firms Ratio Architects and Browning Day Mullins Dierdorf. "We were always trying to maintain the character of that space," says BDMD's John Dierdorf. "The reputation of 'people swim fast here, maybe I can too,' was something built into the original design. With the renovation, we were not going to change any of that."

More from AB: Advances in Dehumidification Efforts Target Chloramines

Instead, the focus was on enhancing the experience for both athletes and spectators. "As we walked through and strategized on the project, we asked, 'What are the overarching priorities?' Water quality first, air quality second and aesthetics third," says Nick Davis, an associate partner at BDMD. "And money was allocated specifically to strategies within those categories."

A final priority was to minimize the disruption of the natatorium's operating schedule. "We tried to maintain the schedule as best we could and work around major events," Morrison says. "We did have to close for a few months at a time, but we planned that for when there was more downtime. We tried always to keep the instructional pool open. When we were working in the major space, we kept that open for swim classes and practices. It worked quite well."

![While the pools remained largely untouched, renovations were made to the building infrastructure, lighting, water- and air-filtration systems, and diving platforms. [Photo courtesy of Indiana University]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2016/09/ab.aquatics916quote1.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) While the pools remained largely untouched, renovations were made to the building infrastructure, lighting, water- and air-filtration systems, and diving platforms. [Photo courtesy of Indiana University]

While the pools remained largely untouched, renovations were made to the building infrastructure, lighting, water- and air-filtration systems, and diving platforms. [Photo courtesy of Indiana University]

THIRTY YEARS OF CHANGE

As environmental conditions took their toll on the building during its three decades of use, changes in the world outside the Natatorium's walls further separated it from newer facilities taking advantage of technology that simply didn't exist at the time. "The guts are more efficient, effective," says Dierdorf. "We get the benefit of newer technology relative to the old equipment."

Nearly every aspect of natatorium the mechanical systems — filtration, air quality, lighting — had evolved since the IU facility opened. "At the end of the day, that's what resonates with the operators and users," Dierdorf says. "Some of the things that make a good natatorium are going to have to do with the pool tank, how deep the water is, what kind of lighting is in the space, what the water quality is like. Those are things we think about that weigh on the swimmers that have nothing to do with how much they trained or how fit they are."

The renovation also took advantage of changes in air quality control technology, benefitting both athletes and spectators. "The spectators have a better environment to sit and watch, but it's also healthier, better-filtered, cleaner air for the competitors to breathe," Davis says. "Thirty years ago, that was as good as it got, but we had the ability to enhance that today."

More from AB: How to Treat Common Pool Water Chemistry Problems

Beyond technology, design standards have evolved, as well. "The Natatorium was pre-ADA, but not by much," says Morrison, noting that features now considered ADA standards were included in the initial design, with some modifications over the years. "We had to add more spectator seating for people with disabilities. We had added an additional viewing platform within the past several years and added a second one in the renovation."

Another accommodation included the widening of the diving platforms to allow for synchronized diving, which wasn't a sport when the venue opened. "The big thing for divers — particularly from the 10-meter platform — is being able to discern where the surface of the water is," Dierdorf says. "When you're spinning around, it can be a challenge to pick up where that water is and complete the dive in the right manner. We've worked over the years with diving coaches to help them with their facilities. I think it showed up pretty well on the recent diving trials."

The goal has always been to be just as important to the everyday lap swimmer or parents teaching their child how to swim all the way up to the Olympic athletes.

The goal has always been to be just as important to the everyday lap swimmer or parents teaching their child how to swim all the way up to the Olympic athletes.

A DIFFERENT ENVIROMENT

Despite the focus on preserving the feel of the old Natatorium, there are some significant differences. "When we reopened, the first thing everybody noticed was the lighting," Morrison says. "It's far brighter. We went with LED, and when you coupled that with painting the building and putting in new skylights, the brightness of the facility was totally different.

"Second, you can really tell the difference in the air quality," he continues. "You go into an old pool and you can smell the chlorine and the chemicals, and it's moist. There's a very noticeable difference now; it seems like a normal building."

The new systems not only create a more pleasant environment, but are more efficient, as well. All new IU construction projects aim for LEED Gold standards, and LEED Silver or better for renovations. This focus on sustainability carried over into the operational side, with the Natatorium becoming the first zero-waste athletic facility in the state, meaning that at least 90 percent of the waste generated by operations is diverted to recycling or composted. The university worked with food vendors to include more compostable or recyclable wrappers, and special care was taken to create signage to raise awareness of and encourage proper disposal.

More from AB: Green Becomes Welcome Adjective in Aquatics Industry

Moreover, the building's new LED lights, filtration systems and other upgrades all contribute to operational savings. Says Davis, "The old lighting fixtures may have been one kilowatt per lamp, and the LEDs are a fraction of that."

Morrison says the renovated Natatorium hasn't been open long enough to gauge the full impact on operational costs, but he expects it will be significant. "Our goal in our mechanical replacement is to have simple payback of five to 10 years, and we fully expect we'll meet that."

And rather than wait another 30 years for another renovation, the new budget will accommodate more frequent upgrades to keep the facility on par with its peers.

For now, Morrison and the rest of the university are basking in the reward of their efforts. "The good thing is that it's getting rave reviews from everybody from recreational swimmers to world-class athletes," he says. "The goal has always been to be just as important to the everyday lap swimmer or parents teaching their child how to swim all the way up to the Olympic athletes."

This article originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of Athletic Business with the title "Behind the renovation of the world’s most iconic swimming venue"