Video displays are getting fans closer to the action than ever before, thanks primarily to advances in LED technology.

For years, facility owners have been using video boards to enhance the entertainment value of sporting events with instant replays, statistics, sports-ticker information, close-up images of players and even images of the fans themselves.

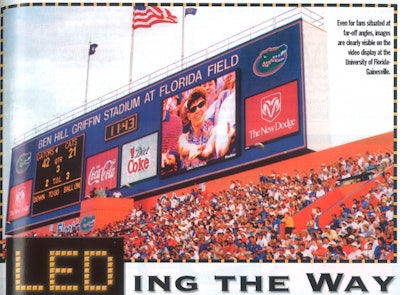

Even for fans situated at far-off angles, images are clearly visible on the video display at the University of Florida (Original Image from Sept. 2000 Issue of Athletic Business)

Even for fans situated at far-off angles, images are clearly visible on the video display at the University of Florida (Original Image from Sept. 2000 Issue of Athletic Business)

Foremost in the picture, both for video display systems and scoreboards, is light-emitting diode technology. Although LEDs have been around since the 1960s, they were then only available in red, and their light output was not sufficient for outdoor use. Yellowish-green and amber LEDs became available in the 1970s, and brightness improved dramatically through the 1980s and early 1990s. But it wasn’t until the late ‘90s that the technology was capable of producing clear video, with the development of true blue and green LEDs that, combined with the existing red, could create images in 16.7 million colors. Today, as the technology becomes more affordable, LEDs are increasingly used in scoreboard applications, and are taking over large-screen video completely.

“Over the last three years, LED displays have more or less replaced the more mature technologies,” says Chris Williams, principal for Wrightson, Johnson, Haddon & Williams Inc., a Dallas-based consulting firm that advises clients on video display purchases. “They’re dominating the industry at the moment.”

In particular, LED displays have taken hold outdoors, becoming the standard in just a few years. Given the greater viewing distances in outdoor applications and the interference of sunlight or city lights, outdoor boards must be about four to six times brighter than indoor boards. Thus, LED boards, which are much brighter than earlier boards, are ideal for the outdoor environment. But despite the added light, the boards’ power consumption is significantly lower than that required by older technologies, which include incandescent bulbs, projection systems, liquid crystal display (LCD) technology and cathode ray tube (CRT) displays. Moreover, barring technical breakdowns, LEDs generally last at least 100,000 hours until they’ve exhausted 50 percent of their original brightness. That’s about five to 10 times longer than any of the previous technologies.

“LEDs have set some new standards in the industry as far as longevity and maintenance,” says G. Todd Lathan, senior director of project management for OSI Sports Marketing, a consulting firm in Spokane, Wash., that helps arenas and stadiums design, build and buy video displays. “They run a very long time, virtually trouble-free.”

In the indoor market, LED displays have caught up to the competition, and are starting to step ahead. Previously, the biggest selling point for indoor applications was weight. For indoor setups, especially those in which a video board is suspended from the ceiling structure or mounted on a center-hung scoreboard, lightweight boards are often key.

“In the indoor arena, the LED has its biggest advantage over CRT because it’s much lighter,” says Dave Belding, vice president of technical operations for Mitsubishi, which manufactures video-display systems. “The CRT typically was too heavy for most of the applications.”

But despite this inherent benefit, many indoor facilities in the past did not choose LEDs because of limited potential viewing angles, which are a greater concern indoors because of tighter spaces. Today, however, viewers positioned to the side of an LED screen at a 170-degree angle, can see the image clearly.

LEDs themselves are solid-state devices that emit light when electric current passes through them. They can be separated into three main structural categories, according to Dave Foster, assistant vice president of product development for Trans-Lux, a manufacturer of video displays. In the most prevalent type, lame LEDs, a “lead” frame includes a “reflector cup” that increases light intensity by focusing it forward. The light is further directed by an epoxy lens, which protects and surrounds a light-emitting chip. A second type, surface mounted lamps, reflects light with a metal frame molded around a light-emitting chip. These are mounted flat to the board, offering wider viewing angles than the standard lamps while using less area, which allows for higher resolution. Since they are not nearly as bright, however, they are generally restricted to indoor use. A third type is also primarily used indoors. Commonly referred to as “chip on board,” this lesser-used variety places the light-emitting chips and their wire connections directly on the board, without reflectors to direct the light. These are often less light-efficient and harder to maintain.

All three types have at their core the same light-emitting chip, a chip so tiny that 500 can fit in a package the size of a postage stamp, Foster says. The chemical composition of the chip determines the color of the light emitted. Red LEDs, for example, generally consist of the chemical compound aluminum indium gallium phosphorus, although some companies substitute arsenic for the indium and phosphorus, which provides a deeper red but less brightness. The chemicals are added to a core “wafer” through a 12-step process. Green and blue LEDs, on the other hand, have about 80 processing steps in their “recipe.” The process begins with silicon carbide or sapphire wafers, and then adds gallium nitride to the mix through a process that might mean pulling the compound under a vacuum, putting the compound under pressure, vaporizing materials or changing temperatures. Due to the much greater complexity of their manufacture, green and blue LEDs all came from a single manufacturer in Japan until a few years ago. Now, many more companies have refined the process, increasing competition and quality. Green and blue LEDs still cost about five times as much as red, but the difference is continually decreasing, making video boards available to a larger market.

“The advent of an affordable blue and green has strongly contributed to the spread of a viable video alternative,” says Chris Merrill, marketing manager for Trans-Lux Sports. “It really hasn’t been until just the last few years that blue and green were affordable for colleges or even some professional teams.”

The video image itself is formed from “picture elements,” or pixels. Indoors, a single LED constitutes a pixel. Outdoors, multiple LEDs are combined into each pixel, creating the additional brightness necessary. The distance between the center points of the pixels, or the pixel pitch, combined with the physical dimensions of a screen, determines the resolution. The smaller the distance between pixels, and the more pixels incorporated into a display, the higher the resolution. As time goes by, demand for tighter resolutions is shrinking the pitch of indoor and outdoor video displays.

“The pitch of indoor screens in typically between 5 and 12 millimeters, outdoor screens from 20 to 40 millimeters,” says Bob Klausmeier, president of Sports Media Systems/Philips, which specializes in the design, installation and operation of multimedia systems for public venues and events. “Last year, many indoor screens were sold with a 16 millimeter pitch. Now, you virtually never see that. Everything’s specified as 12 millimeters or smaller. You used to see a lot of new outdoor screens specified at 30 and 40 millimeters of pitch. Now, they’re typically specified at 25 and smaller. A year from now, you’ll probably see the same jump in quality.”

But better resolution does not always guarantee clarity. Like a television screen, the image is dependent on its source, whether live video or VHS or BETA feeds.

“If you have a horrible source, it’s going to look horrible on the screen,” says Bill Himaras, project engineer for SACO Smartvision Corp., a video-display system manufacturer. “If your source has a lot of noise in it, you’re going to see it on your screen.”

Which means that before deciding on a video board, buyers must consider where they will be installing the board and how they will set up the video feeds and wiring. The location will also help determine some of the specifications for brightness and resolution, depending on viewing distances and angles.

Another factor that must not be overlooked is cost. While LED boards cost significantly less to buy and operate than the older boards, any video display system will add a significant amount onto the cost of a basic scoreboard.

“You’re going from the hundreds of thousands to the millions of dollars very quickly,” says Mitsubishi’s Belding.

Much of that cost can be negated, however, through advertising and sponsorships. Charged on either a per-minute or an exclusive basis, advertising can range from television commercials played on the video board to advertising messages that scroll along the bottom of a large board or in a small ribbon board. To try to make advertising less intrusive, many facility operators choose a single advertiser to sponsor their boards, or one advertiser in each of a small number of product categories, within which each remains the exclusive sponsor. Facility managers might also eliminate the traditional static advertising panel attached to the scoreboard and instead offer opportunities for advertisers to sponsor particular video moments, such as halftime highlights or instant replays. Advertisers might even be credited on the video display as the sponsor of the starting lineup.

Thanks to such increased advertising opportunities and reduced video board prices, the technology is becoming available to a wide assortment of venues. Five years ago, it was rare for a college facility to have an instant-replay board. Now, even high school facilities have added boards. According to Mark Steinkamp, marketing manager for scoreboard manufacturer Daktronics Inc., which has installed high school video boards, the scaled-down versions cost between $100,000 and $200,000. Most college and professional boards, however, cost several million dollars.

“More and more high school facilities will have video displays in their athletic facilities as technology continues to improve and pricing continues to go down,” Steinkamp says. “Before, a lot of facilities couldn’t even consider having a large-screen video display.”

From AB: Tech, Funding Drive High School Scoreboard Upgrades

It’s not just LED technology that attracting the attention of facility operators. It’s also the possibilities that lie ahead. Already, screens are becoming wider, and on average are two to four times larger than older displays. They will probably continue getting wider as facilities position themselves for the potential transition to high-definition television, which some industry observers predict may begin in about a year. Also referred to as digital television, HDTV boasts 720 lines of resolution or more (compared to 600 lines for a regular television and 120 lines in a typical arena or stadium video display), but requires about 20 to 25 percent more power. While standard screens require a height-to-width ration of 3-to-4, HDTV uses a 9-to-16 ration. In preparation, some facilities are purchasing a board structure sized for HDTV, but filling the currently unnecessary space with removable ad panels.

Programming is also changing as technology advances. For one thing, boards are filling multiple needs. While most video displays already ran be electronically subdivided to show multiple images at once, manufacturers have recently introduced modular systems that can be physically separated into 30 to 40 manageable pieces and moved to other locations. That way, a board usually stationed in a college’s football stadium can be moved indoors for commencement ceremonies. Some companies are also enhancing amenities for fans. For years, facility managers have been increasing interactivity between fans and the boards through games, animation and cheermeters, among other things. Now, some boards keep fans engaged by linking to out-of-town game information and other news they can use.

“It used to be that you could use one of these full-color boards for video only,” Merrill says. “Now, we can run feeds to the boards from a news service or sports ticker or a stock exchange. People are multitasking while they’re at the game, and the board is reflecting that.”

Someday, a new technology may emerge to challenge LED supremacy in the realm of large-screen video, but the wait may be long. A product called “flat screen,” a production of the U.S. Department of Defense, probably won’t be seen in stadiums and arenas for many years. Researchers have been experimenting with fiber-optic displays, but haven’t yet been able to create one bright enough. It’s probably only a matter of time, however, since tiny fibers can be pressed very tightly together to create superior resolution. On the more immediate horizon is Digital Light Processing™ (DLP), an all-digital projection system from Texas Instruments. An image is translated into digital code through the DLP formatter board, and then sent to a Digital Micromirror Device™. In the DMD, more than 500,000 microscopic mirrors build the digital image by rapidly switching on or off according to the image’s code. Once a light beam reflects this image off the DMD’s surface, color is added by filtering or splitting light, and then a lens magnifies and projects the image onto a screen. Right now, DLP’s development is limited mainly to business projectors, cinemas and trade shows. So for now, it is up to LED to keep developing at a rate fast enough to appease and entertain the masses, and keep them coming to sporting events, not just couched in front of their TVs.

“The whole point for the fans is that someone sitting in the back row gets to see the same thing that someone up front gets to see,” says Sports Media Systems’ Klausmeier. “It’s a merging of the at-home TV experience with being at the game.”