Major League Baseball's steroid saga has sparked expanded drug testing at the Division I level.

Last year marked the first-ever implementation of 12-month testing in two sports: football and baseball. The NCAA's most recent survey data show that those sports lead all others in terms of the percentage of participants who admit anonymously to using performance-enhancing drugs. That 2.3 percent in each case may seem minuscule at first glance, but the self-reporting nature of the survey leaves it susceptible to inaccuracies. And even if the number is dead on (historically, the actual percentage of positive tests has been similar), it still represents hundreds of student-athletes. "I don't focus a lot on the actual percentage; I look at trends," says Frank Uryasz, president of the National Center for Drug Free Sport, which administers the NCAA's drug testing programs. "Whether it's 2 percent or 3 percent is not as important to me as whether the percentage is going up or down. In football it has been going down. In baseball it has not."

In November 2005, mere months removed from the much-publicized Congressional hearings on steroid use in Major League Baseball, the American Baseball Coaches Association lobbied the NCAA's Committee on Competitive Safeguards and Medical Aspects of Sports to implement year-round testing in Division I. The association quickly allocated the necessary funding, and summer testing began in 2006. "The Congressional hearings got us thinking, 'Shoot, this is scary,' " says ABCA executive director Dave Keilitz, who personally spoke to NCAA president Myles Brand about his concerns. "We don't know what the problem is at the college level, or even if there is one. But we wanted to use this as a preventive tool, because if kids know they're going to be tested, hopefully they won't use performance-enhancing drugs."

Previously, the NCAA concentrated much of its testing efforts on teams participating in post-season championships. Randomly selected representatives of all 64 teams in the 2006 baseball regional field were tested, and super regional and College World Series qualifiers were, too - with repeat tests possible for any given student-athlete. "You don't want the kids to think, 'Well, we got tested in the regionals, so we won't get tested again,' because then you leave the window of opportunity open for drug use," Uryasz says. "The athletes have to know that testing can and will occur at any phase of the championship."

With regular-season testing in place but spotty, the summer months represented the last true loophole for users. It also introduced new logistical challenges for the NCDFS, which employs as many as 400 test collectors nationwide, working under the direction of some 60 crew chiefs who typically represent the medical community in some capacity. Last summer, some tests required crew members to travel five hours by car. Others had to board planes to reach select student-athletes. "Not all student-athletes are sitting on their campus taking summer classes," Uryasz says. "In fact, with baseball, most of them aren't. A University of Arizona student-athlete might be playing summer baseball in Alaska or Cape Cod."

"We had five of our players tested last summer," says University of North Carolina baseball coach Mike Fox, adding that the players were scattered in summer leagues up and down the eastern seaboard. "That's the tough part about testing baseball players. They're generally playing in summer leagues, and they could be all over the country. Fortunately for me, I was not directly involved in having to track our players down."

That responsibility often falls upon athletic department officials, who are now required to know the whereabouts of their student-athletes at all times. The NCDFS provides 48 hours warning of a pending test, and athletics administrators must immediately produce a roster of active players. The athlete gets 24 hours notice, once the NCDFS has made arrangements to send a collector to the athlete's summer location. The stakes are high. An athlete who can't be found may be treated by the NCAA as a no-show, and potentially presumed a performance-enhancing drug user by default. Bill Clever, compliance director at the University of Oregon (which doesn't field a baseball team), held a meeting with football players last spring to gather their summer itineraries. "Our fear is that someone goes camping where there is not cell phone access," Clever told the Oregon Daily Emerald in June.

Uryasz understands. "I feel sorry for the compliance people, because you can tell these kids that they need to keep the department apprised of where they are, but they're college students. They don't usually pop their head in the compliance officer's door and let them know that they're leaving," he says. "So, yeah, it gets fairly complicated, but it works."

It worked well enough from an administrative standpoint last year to establish summer drug testing for all NCAA sports in 2007. Just how many athletes are expected to receive their 24-hour notice is unclear, according to Uryasz. "Even if I have a feel for it, I don't make that information known, just because we don't want kids calculating the risk of being selected," he says, adding that the only way in which the NCAA's drug testing program is likely to expand, now that it has gone year-round, is to increase the number of tests administered in any given month. "We're always trying to figure out how to minimize the number of tests and maximize the deterrent effect, but I'm afraid that's more art than science."

How well the NCAA's expanded dragnet actually worked at catching cheaters last summer remained unknown as of this writing. The NCDFS was to present its test results to the NCAA in mid-December. However the 2006 numbers shake out, those charged with overseeing the integrity of collegiate sports are satisfied that summer testing represents another step in the direction of deterrence.

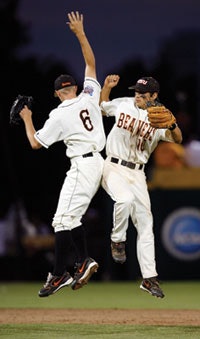

"Personally, I like it," says Fox, whose Tar Heels placed second at the 2006 College World Series. "It's certainly a bold step by the NCAA." As a UNC head coach, Fox is familiar with bold steps. In 2005, athletic director Dick Baddour announced that UNC athletes testing positive for anabolic steroids would be permanently dismissed. "He came into a head coaches' meeting and said, 'We're going to have a zero-tolerance policy for steroid use. End of discussion,' " Fox recalls. "And there was no discussion. There wasn't one coach in our department who questioned that decision. Obviously, it sent a very strong and clear message to our student-athletes."

Whether players elsewhere are getting the NCAA's stronger anti-drug message remains to be seen. The percentage of admitted performance-enhancing drug users in Division I baseball did not budge between 2005 and the NCAA's previous survey in 2001. The next survey won't be conducted until 2009. In the meantime, Uryasz will continue his now year-round efforts in earnest. "If athletes feel that in order to compete in their sport they have to use performance-enhancing drugs, then I think we have a problem," he says. "People tend to perceive the percentage of users as higher than it actually is, but we believe that percentage should be zero. Two percent is not a satisfactory number for us. And in that sense, you never can stop testing. There always has to be that deterrent out there."