Cities Use Recreation to Help At-Risk Teens

The rash of school shootings in recent years has thrust a small number of disaffected youths into the national spotlight. It's apparent to a growing number of recreation professionals, however, that for every kid who grabs attention by bringing a gun to school, many more troubled teens slip through the cracks unnoticed.

At-risk youth recreation programmers agree that the key to helping teens is simply getting them to show up for a group activity. "Recreation is always the hook," says Manny Tarango, recreation supervisor of the at-risk youth division for the Phoenix Parks, Recreation and Library Department, which has eight youth centers. "Whether it's a basketball league or some other type of activity, recreation usually gets them in the door. From there, we focus on trying to find out what a child may need, and then set up activities, special events, speakers or mentor relationships to address those needs."

The Phoenix at-risk youth programs focus on the 13- to 19-year-old age group, and the teen centers offer open recreation, youth employment services, counseling and mentoring, as well as leadership opportunities through a teen council. According to Tarango, anywhere from 200 to 300 teens may show up at one Phoenix teen center on any given day.

In addition to its other services, Phoenix also has a diversion program for youths who have committed a first offense. Rather than incarceration, the youths can complete community service work and take classes through the recreation department. They may clean up a park or a vacant lot, or attend classes on violence prevention or substance abuse.

Seattle's recreation department offers a late-night recreation program designed to target at-risk youths who may not come to the city's community centers otherwise. When asked what he feels are the most effective ways to get teens into a center, Dave Gilbertson, teen advocate for the Seattle Parks and Recreation Department, says, "Basketball and food. A lot of teens will come in for those reasons, and that gives us a chance to talk to them, get to know them and start building a relationship with them. Then we get a better understanding of how we might be able to help them if they are having problems."

Provided at five recreation centers from 9 p.m. to 1 a.m. every Friday and Saturday night, the program draws about 80 teens per center per night, according to Gilbertson. All late-night programs feature music, but occasionally a center will offer music-related activities, including dances, open microphone sessions and disc jockeying lessons. When these types of activities are offered, Gilbertson estimates that the center draws in excess of 100 youths.

Since many of Seattle's 25 community centers are located near high schools, community center staff members build a relationship with students and staff at schools to help promote the late-night recreation program. Although it's more difficult to inform youths who are not attending school on a regular basis, staff members find ways to communicate with these teens, as well. "Kids who may have dropped out of school or who are not involved in community activities will tend to congregate at our teen centers," says Gilbertson. "We'll see kids who we know aren't regularly attending school, and our staff will talk to them, hand out a flyer that explains what the late-night program is about and tell them that they're welcome to participate. Once they become familiar with it, they're good about bringing their friends."

The recreation department also partners with the Seattle Police Department during late-night programs. Police officers regularly attend the programs, and when officers are out on patrol, they invite kids who are on the streets to become involved in the program. According to police, crime has been reduced an average of 30 percent near the late-night centers since the program began about eight years ago.

Phoenix has seen similar results since it began its at-risk youth programs seven years ago. Both youth crime and youth violence have decreased, according to the city's juvenile court system. "We feel that we've been a part of that," says Tarango, "not only by providing recreational activities for kids during their leisure time, but also by providing a lot of youth development programs."

Another recreation program, called the Get R.E.A.L. (Recreation Education Activities Leader) Roving Leader Program, also is designed to seek out at-risk youths. Started in 1998, the Austin, Texas-based program targets the eight most violent crime areas in the city (deemed so by the Austin Police Department). Two staff members are assigned to each area, and they go to different sites in vans stocked with equipment and supplies for impromptu games, crafts and athletic activities.

"We're targeting kids who aren't already connected to some type of youth provider," says Joanna Mesecke, program manager for the Austin Parks and Recreation Department. "We just sort of set up shop wherever the kids are; it may be a playground site, a street corner, a housing authority or a school."

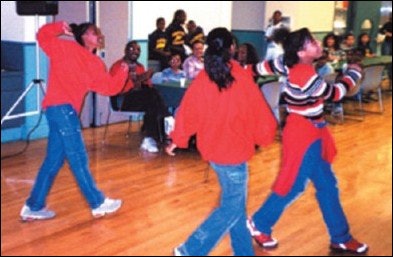

The activities vary from day to day, depending on what resources the particular site has to offer, as well as what activities the youths choose. The roving leaders may ask the kids to meet them at a recreation center at a specific time to play team sports, such as basketball, flag football and softball. They may arrange dance or cheerleading activities. Often, the staff members will take kids to state or county parks and offer outdoor education activities, including canoeing, hiking and nature identification classes. Parents or guardians must sign permission slips before staff members can transport any of the children. "Sometimes it's hard to get the kids connected immediately," says Mesecke. "We don't just shove the registration card in their face, because they don't really know us. Trust has to be established before they buy into the program. These are kids who really don't have anyone they can turn to."

In many cases, a roving leader will, over time, become the one person a child feels he or she can trust, says Mesecke. A typical schedule for a roving leader is from about 2 p.m. to 9 or 10 p.m., Monday through Saturday. They are also on call around the clock. Mesecke says staff members have been known to go to a child's home if he or she is having a problem, or to meet a child at the juvenile court and speak in front of the judge if a child is arrested. "Relationships are what it's all about," says Mesecke. "That's how we're going to have the most impact on a child. It takes special people to be roving leaders, people who are willing to sacrifice some of their personal time for the sake of helping these kids out. A roving leader can be a sister, brother, father or mother figure to these kids."

This is not a program that will work for every city, Mesecke notes. "It's expensive," she says. "We have a very generous city council that was visionary and noticed that there needed to be a program like this. We're very lucky in that sense." The program has an annual budget of $1.5 million, and almost all services are free for youth participants.

Not only is the program well supported by the city, it has also been very successful. "We've had kids in the program who are now working as recreational aides at our playground sites or who have gotten other jobs through our youth employment program," says Mesecke. "As with any program, we have some kids who have slipped back into a life of crime or gangs. Overall, though, we've had a lot of success with getting kids connected to some type of positive force."