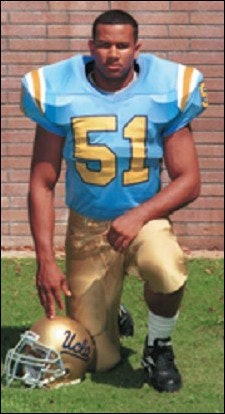

Not long after arriving on the UCLA campus in the fall of 1995, Ramogi Huma heard his calling. As a true freshman linebacker on the Bruins football team, Huma saw the player above him on the depth chart suspended by the NCAA for accepting groceries from an agent. That player, All-American Donnie Edwards, now a member of the Kansas City Chiefs, was in graduate school at the time and, according to Huma, struggling to make ends meet.

"It was disturbing to me as a young player looking at putting four or five years into the system and thinking that this guy, who's contributed so much, has a problem paying bills when so much money is pumping through the system," Huma says. "We understand the reason for rules and why student-athletes shouldn't take handouts. But it's revealing when a player accepts groceries, because it's not like he's accepting money or shoes. You don't accept groceries unless you need to eat."

At the time, Huma expected to hear a nationwide outcry among student-athletes intent on telling the public what playing big-time college sports under NCAA rules is really like. None came. "It was talked about a little bit in the media, but nothing was really said on behalf of student-athletes," says Huma. "That was the point at which I realized that student-athletes really had no voice."

From that moment on, Huma, who earned two degrees from UCLA after a hip injury cut his playing career a full season short, has tried to break the silence. In 1997, he and a few Bruins teammates formed the Collegiate Athletes Coalition, a campus-recognized student group, for the purpose of pushing an agenda of specific reforms related to the welfare of student-athletes everywhere. These include year-round health coverage (as opposed to coverage limited to the academic year and official summer workouts), a death benefit greater than the current $10,000, grant-in-aid that fully matches a school's self-calculated cost of attendance (athletic scholarships currently fall $2,000 short of this figure, on average) and the ability to hold jobs with unlimited earning potential. (As it stands, earnings for student-athletes holding jobs during the academic year are capped at $2,000.)

Of greatest concern to athletics officials is the proposal relating to scholarships. Placing the burden to close that $2,000 gap on athletic departments will simply widen the chasm between the haves and have nots, according to Bill Bradshaw, DePaul University athletic director and president of the National Association of Collegiate Directors of Athletics. "It will significantly impact all of us, because those who are able to fund it are going to have a great recruiting advantage," says Bradshaw, who adds that, contrary to popular belief, not many athletic departments have the budgetary leeway to do so. "And even for everyone who does it, there's going to be a significant gap in revenues and expenses. There's not going to be any more revenue associated with that expenditure."

In addition, if the scholarship shortfall is addressed only for student-athletes in revenue sports, such as football and men's basketball, it could expose an athletic department to potential legal action. For these reasons, Bradshaw doesn't give the issue of beefing up scholarships "too much of a chance" of passing muster among the NCAA membership.

The chance of the Collegiate Athletes Coalition affecting any kind of change is open to debate. The group was slowed at the outset by its own lack of time and perspective. "We struggled a little bit just trying to figure out where student-athletes stood in the system, in the different dynamics of NCAA sports," Huma says. "That's not an understanding you gain as a student-athlete. You have to research it to understand it, and being a student-athlete made it difficult to perform all the things that needed to be done. As a graduate student, I had more time to commit."

To date, the movement has spread from UCLA to fellow Pac-10 schools Stanford, Oregon and Arizona State, and to Boise State of the Western Athletic Conference. Huma, with financial backing from the Pittsburgh-based United Steelworkers of America, has personally traveled to campuses, visiting with student-athletes and encouraging them to launch local coalition chapters. Entire teams have signed the coalition's Declaration of Unity.

If this whole thing begins to sound like a labor union in the making, Huma is quick to set the record straight. "Student-athletes are not employees, so we're not unionizing, and we don't have the right to unionize even if we tried to," he says.

The coalition reached out to the steelworkers in June 2000 for organizational, legal and communications advice, and the union, which has endorsed such campus movements as United Students Against Sweatshops, was eager to help. "We consider these athletes to be exploited in a number of different ways," says Tim Waters, USWA's national coordinator for rapid response and its liaison to the coalition. "I'm a football fan and a basketball fan, a good college sports fan, and I didn't know a lot of this stuff. Most people don't."

The process of formally educating the public began this past January, when Huma officially unveiled the coalition during a press conference at UCLA. The media took the ball and ran, covering the multifaceted story from labor, higher education and sports angles. The movement has garnered airtime on ABC's "World News Tonight" and on ESPN's "Outside the Lines." A "60 Minutes" segment on college sports, airing this month on CBS, will mention the coalition. "It's great for the group, because right now exposure is what we need," Huma says. "For us to go school to school is going to take a while. But if student-athletes hear the message, decide to organize themselves and then come to us, it would be much more efficient."

While exciting, the media attention has not been flawless. "Some of the press that we've gotten has been twisted into pay-for-play arguments, and we haven't put that forth as a goal," Huma says. "Right now progress should be made within the existing structure of NCAA sports. I think scholarships can be adequate if they are actually formulated to meet the needs of student-athletes."

"These students are not making outrageous demands," Waters adds. "They're asking for simple but badly needed things that really affect their performance. I wouldn't think an athletic director or coach would want students out at practice worried about getting hurt. They don't play as well. They know if they get hurt that there are financial consequences. There are some really down-to-earth, reasonable issues here that these athletes are raising. The NCAA has yet to respond in any hard way to these facts, and we're wondering why."

By the same token, the coalition has not yet formally approached the NCAA with its proposed reforms, either. Waters explains: "The NCAA has had 50 years to change these rules, and it has had people ask before for these rules to be changed. When the coalition asks, it will be from a position of having athletes behind it. We're going to go to them and say, 'This is what you need to do. This is what the athletes want. They're unified on this.' That leaves a lot less wiggle room for the NCAA."

NCAA spokesperson Wally Renfro agrees that the coalition's platform is, for the most part, a reasonable one, but he takes issue with the notion that the NCAA is an inflexible entity. "Any time student-athletes have something to say, we're eager to hear it," Renfro says. And there is evidence that the organization is listening - to the coalition and other movements like it, as well as to its own Student Advisory Committees, whose existence is mandated at each member campus and conference. Renfro points to legislation currently before the NCAA membership that would ensure health-care coverage for student-athletes during vacation periods. Moreover, the NCAA's new 11-year contract with CBS earmarks a combined three-quarters of a billion dollars for student-athletes through established Special Assistance and Academic Enhancement Funds, as well as a new Student Opportunity Fund, Renfro says.

"We're always looking at how to better support student-athletes," he says. "Conditions change, circumstances change, times change, and an organization has to adjust to that. Do we have people with good intentions trying to do the right thing. Absolutely. Can we ever say that our job is done and we've met the welfare needs of student-athletes. No. I don't think we can ever get to that point."

Meanwhile, the coalition is content to navigate the playing field of public opinion. In the end, it hopes to hit the NCAA with a groundswell of support that can't be ignored. Says Waters: "If it's not a public outrage, then we haven't done our job very well."