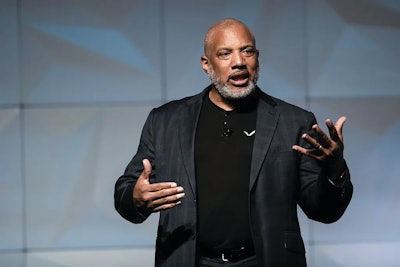

John Register has been clearing hurdles — both literal and figurative — his entire adult life. The University of Arkansas track and field All-American qualified for the Olympic Trials in the long jump and high hurdles in 1988, and again four years later in the 400-meter hurdles. In between, he survived combat with the U.S. Army during the Persian Gulf War. But Register’s future was forever changed while training to make the ’92 Olympic team, when an awkward landing after clearing a hurdle ruptured the popliteal artery behind his left knee. With no hope of returning circulation to his lower leg, it was amputated. Today, as author of the bestselling 10 Stories to Impact Any Leader: Journal Your Way to Leadership Success, Register speaks to audiences about overcoming life-altering obstacles, backed by his own success story that includes a silver medal in the long jump at the 2000 Paralympic Games in Sydney, Australia. AB executive editor Andy Berg and senior editor Paul Steinbach sat down with Register at AB Media’s Madison, Wis., headquarters in late May to discuss his past experiences as context for his upcoming appearance as keynote speaker at AB Show 2025, Nov. 6, in San Diego.

What is your presentation’s theme?

It’s all about “Amputate to Elevate” — what you have to amputate in order to elevate your success.

Is that like addition by subtraction?

It’s what do you get rid of in order to get yourself to the next level? Think of ballast in a balloon. You have to let some things go in order to rise.

What real-life forms might that ballast take?

Usually, when I interview CEOs, the number one thing that comes up is ego. “I have to get rid of my ego.” There are a lot of other things that come up. One lady said, “I had to get rid of alcoholism.” I mean, they go deep into some of these topics.

Can you give us a little background of where you came from?

I’ll kind of reverse it. I’m now in a space where I’ve had all these life experiences, and I’ve been trying to figure out how to package all of them into something that’s valuable for someone else. And it’s just very hard. Where do you start? Where do you end? And so I’ve said, “Okay, you’re the mountain climber guy who’s won a silver medal after having an injury. You’re also a combat veteran. Less than 1% of Americans serve and go into combat. You play the cello. You’re all these things. So how do you put that into something that’s attainable — that’s reachable for other individuals?” What I say is that we all have this 1% of what we do. Can we focus on that 1% and not focus on the 99% of trying to chase everybody else’s dreams — really home in on what do we do best? And can we get a team around us that actually helps us achieve those goals in our life to where we can help someone else achieve something in their life?

How have you personally accomplished that?

How I’ve been doing that is through a resilience action model. As I look at my life, I’ve had this process — over and over again — and it still happens, and that is the resilience action model. It’s a reckoning moment that is realized, or hurdled, when we understand that we don’t get back what we desire to have back. When did some type of change, usually a trauma, impact our life? In my case, my leg was amputated. I don’t get my leg back. I was still thinking that life could return to the way it used to be, and it’s not going to happen. And as soon as I got out of that mindset, I was now free to go into the revision of thinking about what might be possible. And there are multiple lanes that we can access. We just have to get rid of that thought that life’s going to go back to the way it used to be, so that we can be free to think about what’s going to happen next. I’m no longer an Olympic-class athlete. I became a Paralympic athlete. I’m no longer a person who’s going to serve in the military for 20 years as an officer, but I created a Paralympic military sports program that now moves into the Warrior Games, and now Prince Harry is running the Invictus Games. So, we have these parallel paths, if we just focus on that 1% that we have to move us forward.

And this happens more than once?

What I tell leaders is you can celebrate after you’ve made your way through this process, but you have to be looking for the next reckoning moment, because it’s coming. And if you’re not looking forward, it’s going to find you. But if you’re looking forward, you’re more likely to find it than it finding you. And that’s what I think separates the really great leaders from those who are just reacting to things that are going on.

Are you comfortable talking about the injury?

I was training over the 4-meter hurdles, the first three hurdles of the race, and one of the hurdles kind of threw me off balance. I landed wrong, my leg hyperextended, and I kind of did helicopter spin and landed on my back. Broke the popliteal artery behind the kneecap. I was in Hays, Kan. They flew me to Wichita for a 13-hour vein graft operation to take a vein from this leg, invert it, make it an artery, to try to get the blood flow to go. Just wouldn’t work, and so I was left with either a walker or wheelchair for the rest of my life, or take the amputation. It wasn’t that hard of a choice, because I was in so much pain. “If I get rid of my leg, I get rid of my pain. That simple.” It was not that simple. I have more pain after the injury, after the amputation. There’s always a sensation that’s there. You know, I feel my foot. I feel my toes tingling right now. The pain comes when there’s a nerve that gets — I don’t know what happens, but something happens, and it starts firing. I mean, it’s like a hammer on the foot. It’s like a lightning bolt, and I can’t really tell when it’s coming. That happens maybe three or four times a year.

No regrets?

I’m glad I did it. I said, “Let’s just get it done,” because I was going to be left with pretty much a useless leg with a flex in my knee of about 10 to 15 degrees. That’s not life. I mean, mobility wise, that’s not what I want to be. And I hadn’t really seen anybody on an artificial leg, but I figured, “Well, they have them, so I probably can learn how to walk on one.”

Did you ever deal with the realization that “I’m not I’m no longer whole”?

It was more gratitude. There was a lot of pain, and I knew it was going to get worse before it got better. I knew that. I was thinking about healing on the inside. So, all my military training is going in now, all my sports training is going in — running for Arkansas and being at the highest level. So, I knew the pain is coming, right?

It sounds like you’re identifying the reckoning.

I’m in the reckoning moment. I’m reckoning with the fact things are not going to go back to the way they used to be. And that gets me to the gratitude, because I was also thinking about where I was on that day — May 17, 1994. I was around a group of Army service members who all had at least basic triage knowledge and knew how to handle a battlefield situation, if somebody is blown up or whatever. They knew what to do, what not to do. And even I was coherent, right? “Don’t give me any water. Am I going into shock?”

How hard of a transition was it from Olympic-class athlete to Paralympic athlete?

I had to learn how to manipulate a wheelchair to a prosthetic appointment, learn how to put on an artificial leg, learn how to walk on that leg, learn how to then walk without crutches and walk without a cane. And then, eventually, learn how to walk free, then run and then jump. To jump to a silver medal, that took seven years. I didn’t just put the leg on, and all of a sudden I’m a medalist. I was an 8.30-ish-meters jumper with two legs. My first jump with one was like 2.95. I laid out, and I cried. I just literally cried. I was like, “This is going to take a lot of work.”

Had you always been comfortable speaking to large groups?

My dad told me, I think when I was third grade, I refused to go to school because I had to speak. I was crying, terrified. He’s a former pastor, and so he got me up in front of church to get comfortable doing readings and things. I could get up and read and that was fine. And then I started playing cello and doing recitals, then singing, and so I was always on the stage. So, I always thought about of it as a little bit of acting. Now, it’s something that’s totally crafted. It’s done with care for the audience. Where I thought you’re going to go with that question is, “Have I ever been comfortable sharing that story?” The answer is, no. I was too afraid to go deep into what was vulnerable for me.

Do you consider yourself an inspirational speaker?

That’s a word that I used to really loathe — inspiration. I never wanted to be the inspirational guy. When I was running for Arkansas, running for the military, running at the Olympic trials, a sports writer would come out, interview me, and I’d be on the sports section of the of the news that night. But when I became a para athlete, I became the inspirational story. I wasn’t on the sports page. I was on the human-interest page, and that bugged me. It just ticked me off. I’m still this athlete. My mindset is there. Why are you making me the feel-good story? I went through a little bit that process that a shared earlier and I shifted from loathing that word to actually it being a part of my whole identity.

You’re okay with it now?

I realized that inspiration comes from the Latin “in spiro,” which means to breathe into. I’m breathing life into my creative, breathing life into myself, and I’m breathing that life into others. That’s what I always want to do. If I’m taking it away, I’m causing people to panic, because they’re struggling to get oxygen. So, I became an inspirational speaker, because when the audience leaves, I want them to be inspired so they have breath to do what they need to do — to rise.