As student-athletes trade high school loyalty for athletic glory, many states are tightening their transfer-eligibility rules

Dan Boyd has been involved with high school athletics in one way or another for almost 40 years as a coach, a principal, a superintendent and, finally, as a detective. That's right. Boyd is the associate commissioner for compliance, administrative operations and legal affairs for the Florida High School Activities Association - which is a fancy way of saying he investigates the legitimacy of several hundred student transfers every year.

That's not an easy task in Florida, a state with one of the most lenient transfer-eligibility rules in the country, thanks to an open-enrollment law that allows students the right to choose a school regardless of their home district. With some exceptions, Florida student-athletes who transfer prior to the start of the academic year or (in the case of fall sports) a season's first practice can participate on that school's athletic teams immediately.

But Florida is far from the only state with such lax policies. When Minnesota enacted open-enrollment legislation back in 1988, more than 30 states (plus Puerto Rico) followed suit - essentially tying the hands of state associations hoping to control the number of transfers.

School loyalty is not what it used to be. "One of the primary reasons for transferring high schools is that kids are trying to make themselves more marketable to colleges," says Traci Statler, a professor of sports psychology at California State University-Santa Barbara, who discusses the issue of high school transfer eligibility in her sports philosophy and ethics class. "Student-athletes are less likely to be loyal to the school their older brothers and sisters went to and more likely to be loyal to the school that can get them what they want - a college scholarship."

"It's a complicated issue, because state associations exist to try to create a fair playing field for all," says Bert Borgmann, an assistant commissioner of the Colorado High School Athletics Association, whose lenient eligibility policy is a direct result of that state's open-enrollment law. "And fair play is at the heart of the transfer rule."

Student-athletes who transfer schools for other than academic reasons open themselves, their team and their new school up to penalties that can range from varying lengths of ineligible periods for the player and hefty fines, forfeits, disqualifications and probationary periods for his or her school. But they also usually displace legitimate student-athletes who have worked hard to earn spots on a given team. Transfer infractions typically occur more in boys' sports than girls', but a wide variety of sports are susceptible - including football, basketball, baseball, soccer, volleyball and swimming.

Illegal transfers and related recruiting violations have been a part of interscholastic sports for a long time. In recent years, however, school administrators and athletic-program observers have been less reluctant to blow the whistle on what they perceive - correctly or incorrectly - as a violation of a particular state's transfer-eligibility rule.

When that happens, the accusing party files the proper paperwork and provides an opportunity for the accused school to respond, says Bob Gardner, chief operating officer of the National Federation of State High School Associations. If that first step leads individuals involved with the case to a belief that the transfer was made for athletic reasons, additional investigating at the school, district or state level ensues, usually involving interviews with principals, athletic directors, coaches, community residents and occasionally teammates.

"You're dealing with a very small percentage of the total number of transfers," Gardner says. "But that small percentage can involve an inordinate amount of time."

That's because many cases stemming from that small percentage often wind up in litigation. "It's pretty difficult to prove that a student went to a certain school because he or she was offered incentives to do so," Boyd says. "But if there's smoke, there's generally fire somewhere. I take all of these pretty seriously, because I know how much emphasis is placed on winning. This is an area that, frankly, can be abused very easily. A student can say he wanted to transfer from School A to School B because School B has an outstanding culinary arts program. He's got no interest in culinary arts, but his eligibility waiver is approved because he said the transfer was for academic reasons. I've seen that happen."

"It's tough, because you're dealing with certain segments of the population that have the resources to just pick up and buy a second house in a different district," adds Gary Phillips, the assistant executive director of the Georgia High School Athletic Association, which requires that an entire household make a bona fide move in order for a student to be athletically eligible. "Making payments on two houses is not a problem for them. If they have the resources to use the rules to their advantage, there's not much you can do about it."

This year, several states used the resources at their disposal to revamp convoluted transfer policies in an effort to restrict the mobility of student-athletes and administer significant penalties to violating players and schools. Other states are in the process of making similar changes, although some need support from legislators to help make amendments to state open-enrollment laws.

Officials at state associations across the country are striving to make athletic directors, principals and even guidance counselors more aware of what's at stake regarding transfer students. Yet schools are where the communication seems to break down, as transfer-eligibility guidelines often fail to be clearly spelled out for players and parents in student-athlete handbooks and at preseason meetings. Consider two recent incidents:

• After three-sport Heritage Christian senior Joel Hoberg played baseball with Milwaukee Lutheran's club team last summer, he considered transferring to the school and participated in two soccer practices at Milwaukee Lutheran. Just before classes began this fall, however, Hoberg opted to remain at Heritage Christian. That's fine, ruled the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association, but Hoberg is now ineligible to play sports his entire senior year because he practiced with one school but attended another one. "We didn't know he was breaking a rule," Hoberg's father told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

• Gresham (Ore.) High School's highly ranked volleyball team forfeited its first three wins of the season this year because one player, whose parents are divorced, lived outside the Gresham district. Her family's primary residence was in another district, but she lived in Gresham with her mother. Oregon students must attend the school district in which they reside, and in this case, the volleyball player's mother did not submit documentation of a legal separation to the Oregon School Activities Association, which would have resolved the matter quickly and quietly. The mother told The Oregonian that she was confused by the paperwork involved. "We thought we had done everything we were supposed to do," she said.

Pleading ignorance, however, is no longer acceptable, Gardner claims. "Generally, states change their rules to address something that's not quite right," he says. "People were taking advantage of the existing rules. States are not trying to make rules that people can't follow, but it's become incumbent on the people in the schools to get the message out about the rules. Somebody using the excuse that he or she didn't know is pretty lame."

State associations are tired of excuses, too. Officials from California to Florida are clamping down on transfer-eligibility abuse. Among the changes:

• In California, the California Interscholastic Federation's Southern Section, beginning next fall, will require student-athletes at its 522 member schools to sit out one year of varsity competition if they transfer without changing addresses. As with most states' policies, exceptions having to do with bona fide moves and hardship cases exist.

Bowing to pressure from the section's 78 member leagues, the Southern Section will be the first of the CIF's 10 sections to impose transfer restrictions. The new policy will eliminate the ability of student-athletes to transfer without penalty. "Open enrollment was getting out of hand," says Thom Simmons, the section's director of sports information, adding that some individual school districts in the Southern Section already had the one-year rule in place.

Simmons says he expects the rest of the state's sections to follow the Southern Section's lead. Representatives of the federation's City Section - where Los Angeles' Westchester High School, which won the 2002 boys' basketball state title, fielded an entire team of players who lived outside of the school's attendance boundaries - will vote on adopting the 12-month waiting period in March.

• With an open-enrollment law similar to California's, Minnesota officials for years have tried to amend the state's law to make it more difficult for students to transfer for athletic reasons. They finally succeeded earlier this year.

"In effect, we really had no transfer rule," says Skip Peltier, an associate director of the Minnesota State High School League. "When you have a state law that allows open enrollment, it's really difficult to go against that. But the climate in Minnesota was right for us to work with state legislators about modifying the transfer rule."

As a result, the league's representative assembly voted unanimously in April to make two-time and mid-year transfer students who don't move into their new school district sit out half the varsity games in their chosen sports for a calendar year. For example, if a basketball player joins a team at his or her new school with only four games remaining on an 18-game schedule, that player must sit on the bench for the remainder of the current season, plus the first five games of the following season.

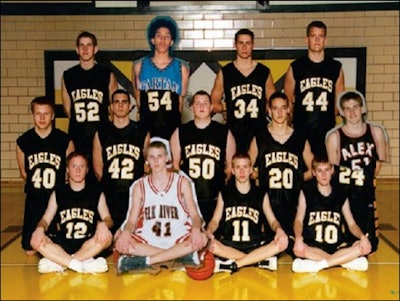

The move should help eliminate scenarios like the one that occurred at Hopkins High School this year, where the top three players from the Class 4A champion boys' basketball team came from outside school district boundaries. "We look at this as good compliance with the open-enrollment law," Peltier says.

• Just a few years ago, Colorado was considered one of the few states where transfer rules were gradually becoming extinct after the state's open-enrollment law went into effect in 1992. But now, CHSAA officials are hoping a slew of newly elected state legislators will go along with the association board of control's decision earlier this year to create a bylaw making first-time transfer students ineligible for half of their games in a calendar year. Currently, with a few exceptions, a student can transfer schools at the beginning of an academic year without an accompanying move and participate in all extracurricular activities as long as that student was academically eligible at his or her previous school. A mid-year transfer who has played a particular sport at the previous school is limited to junior varsity competition for the rest of that season. In theory, a three-sport freshman could transfer three times during his first year of high school without incurring any penalties.

"In our early workings with legislators, we heard everything from 'Don't change the current rule' to 'You're not making it tough enough,' " Borgmann says. "We may find that the policy is too punitive, or we may find that it's not punitive enough. Of course, this whole discussion may eventually be a moot point. But I don't think that will be the case."

• While California, Minnesota and Colorado officials must walk fine lines with state lawmakers on the open-enrollment issue, in Florida, officials at the FHSAA aren't even bothering. "You have to pick your issues," Boyd says. Rather than become embroiled in various political battles, the association has given its blessing to at least five county school districts - most of them in the southern portion of the state - to create their own rules. "All counties have the ability to go above and beyond our rule to do what they need to do," Boyd says.

Miami-Dade County was the first district in the state to amend the FHSAA's policy, barring student-athletes who transfer without a bona fide change of address from participating in all sports (not just varsity) for one calendar year.

Polk, Manatee, Lake and Orange counties have followed. "We're not sure the new athletic transfer policy is the answer, but we have no idea what another answer would be," says Trish Highland, athletic director for Orange County Public Schools, which adopted the 12-month waiting period earlier this year.

Other associations in states with open-enrollment laws on the books also amended their policies in 2002 - in some cases, making them easier on student-athletes.

• In Nebraska, for example, transfer students must now sit out for 90 days, rather than play right away. An original proposal would have made student-athletes ineligible for 180 days. The new policy still requires administrators from both old and new schools to sign a waiver agreeing that each transfer is being made for academic reasons. "Principals thought the previous rule put them between a rock and a hard place," says Debra Velder, associate director of the Nebraska School Activities Association. "They signed waivers for transfers they were not confident were made for academic reasons."

• In Ohio, a new bylaw approved by member schools of the Ohio High School Athletic Association took effect Nov. 1 and actually favors student-athletes by allowing them to transfer to their home school district after enrolling elsewhere. The old policy mandated that transfers to any school wait one year before playing varsity sports. While the new exemption makes for essentially a no-questions-asked policy, it is designed primarily for hardship cases, says OHSAA assistant commissioner Deborah Moore.

A word of caution: In each of these cases, state associations could face legal battles if some constituents contend that new or pending regulations collide with existing open-enrollment laws. In fact, in September 2001, a federal judge ruled against an independent Idaho school district that tried to enforce a one-year waiting period for student-athlete transfers. "We believe the people making the rules regarding athletic eligibility should be the people engaged in those activities every day," Moore contends. "Not state legislators."

But not everyone thinks changing the rules for transfer-eligibility waivers is the only solution to this problem. "I hate to be so negative, but no matter what sort of rules are created, no matter what legal ramifications there are, people will find ways to circumvent the rules," Statler says. "The changing of the rules is absolutely a step in the right direction, but let's be honest - that's not going to solve the problem. I think people are still going to do what they feel they need to do."

Statler advocates making changes at the collegiate level, specifically with how scouts recruit high school athletes. College coaches need to look at players based on their own merits, she says, not on those of a high school's coaches and its athletic program. "We need to be looking at this issue from a variety of angles."

That's exactly what state associations are trying to do, but in different ways. CHSAA officials, for example, encouraged school administrators, coaches, students and parents to participate in an online poll last year asking whether tougher transfer-eligibility rules should be in place in Colorado. About 60 percent of the 4,000 or so voters said yes. "That's pretty overwhelming," Borgmann says, adding that educators have also expressed concerns about how transferring schools might impact a student's academic performance.

Unlike Colorado and most other state associations, the North Carolina High School Athletic Association places the burden of approving or denying transfer-eligibility waivers on the local school boards involved. The state only enters the fray if the school boards are unable to resolve an issue on their own. "We prefer not to call it a burden; we call it local control," says Rick Strunk, an associate executive director of the NCHSAA. "The idea behind this is that the local school boards are going to know much better than us the situation in question. Plus, if we had to look at every transfer that came in and had to rule on it athletically, that would be a terrible task."

But that's exactly what officials in Georgia's state association office do. Last year, they combed through more than 150,000 waiver requests, looking at birth dates, the dates on which each applicant entered ninth grade and the applicant's original school. Usually, only about 2 percent of all requests send up a red flag. "We look at those eligibility reports line by line," says Phillips, who does most of the looking. "Some state associations don't do that. They only review them if there is an eligibility complaint. We try to get ahead of the problems before they happen, and then notify the principals at the schools involved. We try to be of service to the schools. Sometimes, the person filling out the waiver makes an oversight."

Regardless of how states and schools choose to address the issue, it's clear that more transfer-eligibility responsibilities are falling to athletic directors, requiring them to maintain detailed records of which players are eligible to play and at what time. "Most athletic directors are going to be overwhelmed by the amount of paperwork that hits them," Borgmann says, speculating on the impact of Colorado's pending rule change.

Indeed, the transfer-eligibility issue has altered the way high school sports operate - for better and for worse - and policy changes only go so far. But for now, policy is about all the state associations can offer. The rest is out of their hands, and plenty of progress remains to be made. Just ask Boyd. "Hardly a month goes by that we don't impose sanctions on somebody for breaking the rules," he says. "But at least people know we're out there."