New York Turns Horror Into Hope by Mandating AEDs at All Public School Athletic Events

On March 25, 2000, Louis Acompora, a freshman at Northport (N.Y.) High School, was playing goalie in his first lacrosse game. While blocking a shot with his chest, the ball struck Acompora at the precise millisecond between heart contractions, throwing his heart into an abnormal rhythm and sending the 14-year-old into sudden cardiac arrest. He died from a condition known as commotio cordis, which often strikes young people and requires early defibrillation for any chance of resuscitation.

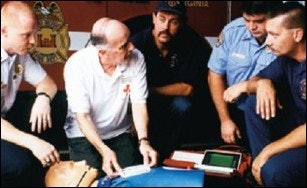

A little more than two years later, on June 27, 2002, in a ceremony at Acompora's Long Island high school, New York Gov. George Pataki signed what he calls "Louis' Law." The bill requires all public elementary and secondary schools to purchase portable automated external defibrillators (AEDs) for use on school property during extracurricular activities, including athletic competitions and practices. The law also mandates schools to train staff members in proper use of the devices. John and Karen Acompora, Louis' parents, were the driving force behind the law, the first of its kind in the United States.

The AED mandate has already paid off. In mid-November, a sideline defibrillator was used to revive 61-year-old John Tierney, who suffered a heart attack in the stands moments before kickoff at a football playoff game between Locust Valley and Seaford high schools. "If these things had been available when Louis was here, we might still have that young man with us," says Robert Christenson, director of physical education and athletics for the Northport-East Northport Union Free School District, which purchased 10 AEDs in June 2000 for about $2,500 each. Today, the district has more than 30 units in nine schools, and more than 300 people know how to use them. "Lives can be saved," Christenson says, "and that's why we have the law."

With the American Heart Association claiming that prompt use of AEDs can save at least 20,000 lives in 2003, it's no surprise that all 50 states have now passed laws or adopted regulations requiring AEDs in public buildings, transportation centers, large office complexes, apartment buildings and other facilities in which sudden cardiac arrest is likely to occur.

Last year, Congress authorized $30 million in federal grants in the first year of the five-year Community Access to Emergency Devices Act, with the intention of helping localities purchase and place AEDs in public facilities and train first responders. A variety of other grants are also available to schools.

And at press time, federal legislation was pending that would establish a national resource center for schools wanting to implement a defibrillation program by providing school-based CPR/AED training programs and fostering new community partnerships among public and private entities. The legislation, dubbed the Adam Act, uses as a model Project ADAM ™ - a Wisconsin-based organization developed in late 1999 in cooperation with Children's Hospital of Wisconsin after Adam Lemel, a 17-yearold Whitefish Bay High School basketball player, collapsed and died on the court from sudden cardiac arrest. In three years, Project ADAM (the first initiative of its kind in the United States) has helped about 115 high schools in Wisconsin start and sustain AED programs.

While New York is the first to mandate AEDs at all public school activities, it won't be the last, predicts Tim Flannery, an assistant director of the National Federation of State High School Associations. "It's going to be a no-brainer, just like you have a fire extinguisher in your building," he says. "We have events that put hundreds to thousands of people in the stands. Good risk managers are saying it's well worth it to have these available if, God forbid, someone has a heart attack. Expecting someone on site to know CPR is a crapshoot. When a state like New York makes a decision like this, it just takes a couple more and then the ground starts to swell."

The ground is already moving in some pockets of the country, usually in communities where a tragedy occurred that could have been prevented with use of an AED. "Most of the programs that have begun have been internally driven by parents and other members of the community who don't want something like that to happen again," says Loreen Utech, national administrator for Project ADAM. Successful programs, she says, involve unlimited access to defibrillators at all times, especially during nonschool hours when school buildings may be locked.

Individuals and organizations from several states, including New York, have contacted officials at Project ADAM, seeking advice and support. Take Karen Violette, for example, a mother of three and the public relations officer for the Ellington (Conn.) Ambulance Corps. Members of the corps were hoping to raise $10,000 by the end of 2002 to buy defibrillators for the community's middle and high schools.

A successful fund-raising strategy is key - especially in New York, where legislators did not provide school administrators with any funding, training or even an enforcement mechanism. With AEDs costing anywhere from $1,800 to $5,000 each, some schools were still "scrounging around" for funds in mid-November - weeks shy of the Dec. 1 compliance deadline - according to Arlene Sheffield, director of school health demonstration programs for the New York State Education Department.

Many New York schools might have benefited from services provided by a new Severna Park, Md.-based company called LifeSignsAmerica, which sells sponsorships to help school districts afford AEDs and proper training. The company hopes to place defibrillators in all Anne Arundel County public schools and provide five years of free training and maintenance in exchange for highprofile placement of 18-by-24-inch billboards with up to 18 scrolling advertisements. Each ad costs sponsors about $100 a month.

Last fall, the Los Angeles Unified School District took a less elaborate approach and simply purchased defibrillators for its 49 high schools at a cost of $3,000 apiece. School nurses trained by the American Heart Association in turn trained athletic directors, coaches and select administrators from each school.

Although more school administrators around the country are realizing the importance of providing access to AEDs in their facilities, some still question the purchase of a device that may not even be used. "The schools are just a piece of the community," Utech says. "This needs to be done as a community initiative. If you put a defibrillator in a school, there's a chance that you might save one life in 10 years. But this isn't just about putting a defibrillator in a school. This is about teaching parents, coaches and students how to function calmly in an emergency anywhere - not just within the walls of a school building. This has a much bigger impact than that."

The impact is certainly reaching far and wide in New York. As a direct result of Louis' Law, about 96 AEDs were expected to be installed in Suffolk County's police patrol vehicles by the end of 2002. A local task force also recommended that the devices be strategically placed in county parks and on public golf courses.

However, because most schools' budgets for the 2002-03 school year were approved in the spring, many administrators requested extensions of the law's original Sept. 1 compliance date. "Most districts are not having difficulty training people," says Nina Van Erk, executive director of the New York State Public High School Athletic Association, which has no official authority in enforcing this law other than requiring that its nonpublic school members comply. "Getting the AEDs is the issue."

To that end, State Sen. Kenneth LaValle is helping underwrite the cost of defibrillators and requisite training by offering $3,500 grants to each of the 39 school districts in his jurisdiction. And at Shoreham-Wading River High School, a student in the school's community relations class was working with athletic director Paul Jendrewski to expedite the purchase of AEDs by writing grant proposals and coordinating volunteer trainers.

Volunteer trainers from local police and emergency response departments are fine, Utech says, as long as they are certified by a training organization approved by the U.S. Department of Health and Family Services, such as the American Heart Association and the American Red Cross. Using volunteers not certified by an approved organization is illegal in many states, she adds.

Although proper training is preferred, Utech cites research claiming that, if necessary, even a sixth-grader can successfully operate an AED. All makes and models have voice prompts that make them virtually foolproof. "There is no way you can screw this up," Utech adds.

That gives Christenson - whose district was one of the first to purchase AEDs prior to the passage of Louis' Law - little comfort. "Were we on top of things by acquiring defibrillators in 2000?" he asks. "Well, we weren't quite as on top of things as we should have been."