Programs geared to youth may differ slightly from installation to installation, but the military's target - making families feel secure - never wavers

Adults can choose a life in the military. Their kids can't. Maybe that's why so much effort is expended making sure children of military personnel are cared for, from the time they're able to walk until well after they're able to throw a curveball or shoot free throws.

But as Nancy Cook points out, sports and recreation is just the beginning of meeting military kids' special needs. "It's hard for a lot of children," says Cook, youth director at the New London (Conn.) Naval Sub Base. "I've had a few in my program whose parents have gone from temporary-duty station to temporary-duty station - kids who, for instance, have been to six different high schools. The military child has more obstacles to overcome, and we have to understand that for the six months that their mom or dad is at sea, we have to be the mother or father figure that they might need."

At the same time, the military's primary function is the fitness of personnel for active duty. That doesn't just mean ensuring they can run an obstacle course or do 50 one-arm pushups. With so many young parents on deployment across the globe, the brass has to give them the peace of mind they need to perform their duties half a world away.

"Essentially, our mission is to support active-duty parents," says Brett Tracy, youth director at Naval Air Station Jacksonville (Fla.). "If they're going out on a ship for six months, they want to know that their kid is with someone they can trust, someone who cares. You don't want them stressed that their kid is in a setting where he's running wild and going crazy. You want everyone to be happy so that when they call home, they have that comfortable feeling that their kids are doing OK. Then they can perform the tasks they need to do while they're away."

To that end, the various military branches run plenty of programs geared to youth. Outdoor sports include the typical variety you might find in a community-based rec program - baseball, softball, soccer, volleyball and flag football. Indoor activities might include basketball, rollerskating, arts and crafts, board games, video games, bowling, ballet, tap-dancing and music instruction.

And those are just some of the activities. The programs themselves are constructed to serve a specific age group, the specific needs of each age group, even specific needs at specific times of the year.

For example, the Air Force divides its program into three core areas: youth activities, youth support and a school-age program. Each of these is further subdivided; youth activities includes the youth sports and fitness program, outdoor recreational programs, specialty camps, the trail program, social recreation, assorted social activities such as dances for teens, instructional programs, the cultural enrichment program and self-directed recreation. Youth support includes community service programs, so-called "youth transition programs" that help kids adjust to relocation, leadership development programs, teen forums and tutoring programs. The school-age program involves school-age day care, a summer day camp program and a program of events that are scheduled during school vacations.

The other branches emphasize most of those areas, and the separate bases create activities that fit under one or more of those umbrellas. But there are probably more similarities than differences in the various programs.

The school-age program is one that every base runs. At Kings Bay (Ga.) Naval Sub Base, the program has several facets. From 6:30 until 7:30 a.m., 36 kids age five through 12 come to the youth center, where they might finish up that day's homework assignment or play games with their friends until they're transported to one of the eight local elementary schools. The afternoon program serves 150 children, the number limited (by military decree) to 20 or 35 square feet per child (the latter if the space is self-contained). Forty children are currently on the waiting list for the program, with dual-income families getting priority because they need the service more than, say, Department of Defense (DOD) civilians or retired personnel living on the base.

During the summer and school vacations, the program expands to include off-base activities such as field trips to water parks, bowling alleys and so on, with different age groups traveling together on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. During those times, the youth center is open from 6:30 a.m. until 6 p.m.

Again, most bases have something like this, although the hours or fees may vary slightly depending on location. Tracy's Jacksonville youth facility runs an afterschool program, for instance, but then stays open later, accommodating open recreation on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 6:15 and 8:15 p.m., Movie or Special Activities Nights on Fridays and Teen Nights on Wednesdays, limited to kids age 13 and up.

Kings Bay's youth director, Patsy Alexander, visited a lot of bases in the 22 years that her husband served in the Navy, and they all had youth centers. Much has changed over the years, however, as the Navy has become more sensitive to parents' needs and more active in setting branch-wide policies specific to youth. For example, Alexander recalls that most youth centers were unstructured, with open recreation being the primary activity. School-age day care, which was under the youth activities umbrella, now is overseen by the Navy's youth activities program with the release of new DOD instructions that require more child-development expertise of its program administrators.

The military is also trying to be more sensitive to the times. Where once children simply walked to a center, signed in, played for an hour and then went home, regulations now require all children to be accounted for at all times.

"They're supervised at all times now," says Alexander. "Security is not so much of an issue on this base, since you have to have a badge to go in and out, but that's not the case everywhere, and the government has deemed it necessary for us to be uniform from base to base. But the issue isn't just security, it's also the possibility of a child getting hurt or lost.

So we provide transportation that's included in the fee now, and parents check their kids in and out."

Another area that's undergoing some change is facility construction and renovation. As the military strengthens its youth programs, more families want to become involved. Administrators of college and municipal recreation programs may complain about a lack of dedicated facilities, but certain military regulations - like the one requiring 30 square feet of indoor space for every child in the school-age day care program - almost ensure that demand exceeds supply.

The Kings Bay base has a fairly new facility, built in 1990, that has a three-quarter-size gymnasium for basketball and rollerskating, but as Alexander points out, both the base and the surrounding county (it's right outside Jacksonville, Fla.) have grown considerably through the decade. "We probably have 6,000 people on the base, and I have 150 children in my program," she says. "I could have more, but I don't have a large enough facility."

Just a few miles away, Tracy's beforeand after-school programs have been run in a 2,400-square-foot building that "just isn't big enough." Now a new building is just about to open, an 8,500-squarefoot youth gym that boasts a full-size basketball court with locker rooms and a teen center upstairs. Tracy thinks that should be sufficient to serve the base's 403 housing units - and anyway, the Navy won't be building him another facility anytime soon.

"We all work within those regulations, and we work with the space they give us," he says. "That's our job."

New London has just completed a study of the base's youth facilities, and Cook is hoping for a new youth rec center. Her base already has two and shares a gym, pool and fields with the adult rec program, but it accommodates more than just submarine commands. Active duty personnel can number as many as 10,000 people at a time - and there are also more than 52,000 retired personnel, reservists, contract employees and DOD employees residing in the area. The number of military family members is estimated at more than 14,000.

Another new facility now graces Spain's Naval Station Rota. The base's programs encompass everything a stateside base would (school-age care, teen, youth), and serves about 6,000 people not counting support services. Half of the new building is dedicated to the youth program, half to the teen program; both sides feature a variety of games, computers, a stereo and a large-screen TV. The teen area also has a snack bar, the youth area a three-room "fun house" that serves the after-school program.

"It's state of the art for Europe," says Joanne Mosher, whose portion of the program serves 400 teens. "My side can have 200 people in it, the youth side 150."

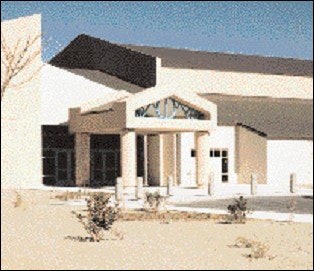

A prime candidate for state of the art in the U.S. would have to be the two year-old, 19,200-square-foot youth center at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico. Its primary activity areas include a gymnasium, a dance and exercise room, before- and after-school classrooms, an outdoor play area and a game room.

According to Nell Buckley, youth specialist at the Air Force Services Agency in San Antonio, 86 of the world's 99 Air Force bases now have youth program sites, with nearly all having dedicated youth centers. "We've seen a number of new facilities and renovations and additions," she says. "A majority of our programs have gymnasiums and outdoor play areas as part of the physical plant. It's all part of the aggressive building program the entire military has had in place for the last five years."

If the building boom hasn't (or won't) touch all military bases equally, that's probably a by-product of another recent trend - increased cooperation with civilian agencies.

"We're much more cooperative. Many of our programs have started working closely with their local communities and have tied in with youth sports leagues that already exist," says Jane Rogers, head of the Navy's community recreation section. "Some of our bases run leagues for their community and the community programs actually blend into ours."

Again, the primary reason is simply that it's better for kids. Children on many bases go to school outside the gates, and most want to play sports with their school friends. ("You don't want to isolate kids and make them feel like they're different or separate," says Rogers.) If the local school system has an established program, the base won't put its effort behind a redundant program. Overseas, the situation is a little different: Local schools will almost certainly fund a football (soccer) program, but just as certainly won't fund baseball.

Bases handle cooperative ventures differently, depending on where they are in relation to the community. In Jacksonville, Tracy says, "athletic associations seem to be left and right, and they're all doing different things. We have the YMCA out in town doing something, the Boy's Club doing something else, and even with the number of kids we have in housing, we just have found that it's working out pretty well to have them out in town doing the different activities that they want to do."

The New London base's housing is not on the base, but right outside the gate, says Cook. Four nearby elementary schools that are part of the Groton school system serve primarily military students. In addition, the base partners with the Groton parks and recreation department. "We don't have enough older kids to play soccer on the base," Cook explains, "so we're part of the Mystic Valley Soccer League."

Private organizations that run base programs are recognized by the base as part of a youth advisory council, the purpose of which is to "ensure continuity and quality of programs," Cook says. These include the soccer league, a youth football league, Little League baseball, Cub Scouts and Brownies, all of which use the base facilities.

Although most military bases undercharge for their programs, most program administrators reject the notion that these various recreational programs are competing for participants. "I think people go to whatever program is closest to them, honestly. We all have the same goal, and if somebody wants to go to them instead of us, that's their choice," Cook says.

Adds Alexander, "We are furnishing something that in the past has not been available through the county and still is not readily available. We try to not charge any more than what they're charging on the outside, and not really to charge that much under. The county and I work together to try to keep our prices as close to each other as we possibly can."

Fees on Air Force bases typically run about 20 percent lower than in the civilian community, Buckley says, and cooperative programs are flying high, with 76 base programs now affiliated with the Boys and Girls Clubs of America.

"We know we're not the only game in town," Buckley says. "We try to meet the needs that our base communities have and at the same time try not to compete with other programs. We certainly know that there are municipal, school and church programs that all want to help meet each community's needs."

Military bases aren't all the same, and neither are the kids on military bases. Some become acclimated to frequent relocation, while others have more difficulty. The youth programs try to be all things to all kids, but it's a struggle.

One area that seems to have fallen through the cracks is kids' fitness. Oh, they play sports, but most program heads say that working out is one aspect of their parents' lives that military kids aren't trying to emulate.

"I don't think fitness is a top priority," says Alexander. "We tried to do physical fitness in our youth program, but haven't been too successful. But then, it's not a high priority for people in general. Schools don't even have phys ed anymore, and people are having to fight to re-establish recess. And a lot of kids aren't taking advantage of a lot of physical opportunities that I would have jumped on had they been available to me at their age. They're watching a lot of TV and playing with the computer."

Alexander notes with a laugh that the military emphasizes kids' fitness, but can't really enforce it. "If you're not fit to serve your country, they can kick you out," she says. "But you can't kick a kid out of his family!"

In some ways, programming for teens is the most difficult part of the youth recreation job. Most bases try to give teens their own recreational and social space, but not all such facilities have taken hold. Kings Bay's dedicated teen center, which was converted from a chief's club, closed after one year because of a lack of participation. The problem wasn't the center itself - it had a dance floor, a DJ booth, a large-screen TV, pool and ping-pong tables, a computer room and bowling center - but may have been the location, which was within walking distance of the gym but not actually connected to the rest of the youth center. It's now going to be converted to a Cyber Cafe.

The frequent turnover at bases makes programming for teens challenging, as does teens' natural wanderlust and...let's call it curiosity. In Rota, Spain, Mosher schedules regular trips to malls on weekends, some as far away as Sevilla, a two hour drive. But it's the same old story: Once they've seen Madrid, how are you going to keep them down on the base. "I hate to say it, but the drinking age here is 16, and we program a lot of activities as a deterrent to drinking," Mosher says.

Building youth centers - giving kids a place they can call home - should sound like a familiar solution to anyone who works with kids, in any setting. Mosher says that, contrary to expectations, the foreign locale in some ways actually serves to strengthen kids' ties to their home base.

"It's really interesting to watch these kids," Mosher says. "When I went to school there were cliques, but these kids aren't so much like that. The seventh graders hang out with the ninth graders. They're all in the same boat, I guess you could say."