Just half a year removed from their greatest legislative triumph, student-athletes face an uncertain future in the NCAA's new federated structure.

Last January, student-athletes sent the strongest message yet to the NCAA's power structure that in the six years since winning the right to speak to legislation on the convention floor, they've become a force to be reckoned with. Student-athletes were instrumental in passing several proposals, including No. 62, which gave athletes the ability to earn the difference between the amount of their scholarships and the cost of attending their institution.

But in June, the NCAA power structure sent a message of its own. Led by the Southeastern and Atlantic Coast Conferences, a move was made to delay implementation of Prop 62 for one year. Although the amounts of money involved are minimal - between $1,000 and $5,000 per athlete, with the typical amount being around $2,000 - conference commissioners and administrators cited monitoring difficulties and concerns about unscrupulous athletes and programs, while coaches complained that most student-athletes lacked the time to hold a part-time job.

Adding to student-athletes' frustration as the crisis unfolded was this first glimpse of their diminished role in the NCAA's new federated structure. Two (non-voting) student-athlete representatives spoke against the moratorium at a meeting of the Division I's management council in late July, after which the group voted 31-3 to support the moratorium. This sent the measure to the board of directors to consider at that body's Aug. 12 meeting - which student-athletes were still holding out hope of being allowed to attend. While the board's decision was not known as AB went to press, no one involved could think of a precedent involving the NCAA board failing to heed the wishes of a virtually unanimous management council. Whichever way the vote went, however, a precedent had already been set - this was the first time a piece of legislation was the subject of a moratorium before it could even be put into effect.

Was this the promise of involvement in the process - defeat snatched from the jaws of victory?

"To keep me encouraged, people kept reminding me that no matter what happens with this moratorium, Prop 62 is law, and so whether it goes into effect now or a year from now, it's going to have to go into effect at some point," says Bridget Niland, chair of the student-athletes advisory committee (SAAC). "But as chair, I was more worried about what this had done to the morale of studentathletes on the committee. It was tough, because we'd built strength each year to get to this point, and now here was this big step backward. It troubled the whole committee."

Federation has brought student-athletes one clear advantage: numbers. Where previously 28 student-athletes served on the national SAAC, each NCAA division now has its own group of student-athletes, meaning that 78 are now involved on the national level. Campus SAACs were mandated at all NCAA institutions back in 1995, and the number of conference SAACs is growing, so more student-athletes than ever are involved.

Their participatory strength was on display in Denver in late July, when all three divisional groups met in conjunction with meetings of the three management councils. Ninety-some studentathletes attended, helping bridge the gaps between all these different groups - or to put it another way, helping the student-athletes overcome the fragmentation that is the federated structure's greatest drawback.

Student-athletes are split on how they are served by the new structure, and not surprisingly, the split runs along divisional lines. Niland, a former Division I athlete at SUNY-Buffalo, is among the most critical ("It's terrible for studentathletes," she says) but isn't at all alone among her Division I counterparts.

"We don't have as much of a voice as we did before," says Tony Coley, a former SAAC member and member of the Miami Hurricanes football team. "Before, we were able to lobby all the members at the convention and sort of appeal to individuals' emotional sides, and they could talk with each other about what the student-athletes had said. But now they have this management council where there are only going to be two Division I student-athletes, and we don't have a vote. We're thinking that the representatives from each of the conferences are going to be coming to council meetings knowing how they're going to vote on proposals, so how are two little studentathletes going to change their thinking?"

Student-athletes from Division II institutions, on the other hand, welcome the chance to bring Division II out of the shadow of Division I.

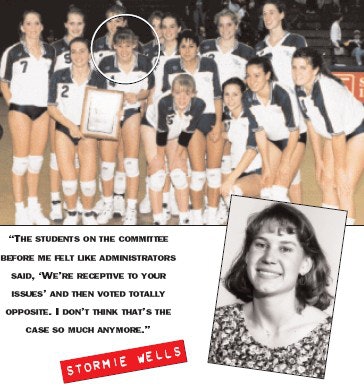

"It's a great move for all divisions, but especially Division II, which sometimes I think is the forgotten division," says Division II SAAC transitional chair Dan O'Callaghan, a former golfer at Rollins College. Adds Stormie Wells, a former volleyball player at the University of Northern Colorado, "I think involving more people is always a better thing. Once the communication networks are in place, and more campus SAACs are in place, it's really going to benefit student-athletes."

And in Division III, the only division to give student-athletes both representation on the management council and voting rights, spirits are high.

"Initially it was kind of scary going into the new structure, but we see a lot of strengths in it," says Division III SAAC chair Julie Fernandez, a former volleyball player at Maryville University-St. Louis. "Even though we're going to be federated, we all still identify with being student-athletes. And now we've got that many more brains to pick for ideas, and that many more people going back to their campuses and getting ideas from them. It's absolutely a bonus."

The last thing this structure seems to need is another committee, but helping to keep the lines of communication open will be a nine-member steering committee made up of three representatives from each divisional SAAC. The function of this committee is still being discussed, but each of the divisional committees are making the creation of a communication network a priority in this first year of federation.

Legislatively, setting priorities for the coming year has mostly taken a back seat to ironing out all sorts of communication and procedural issues, although each division has student-athlete concerns on the horizon.

In Division I, the moratorium has moved the focus from breaking new ground to holding old territory, but the student-athletes have other goals. "For us, the number-one goal is to protect what we've earned," says Niland, "but we all also see building a stronger network as crucial." The national SAAC will be working on getting student-athlete representation on certain committees that they gained under the old structure, such as the Playing and Practice Committee and the Marketing and Promotions Committee.

Meredith Williard, a former University of Alabama gymnast, says that since many decisions in Division I will now be made at the conference level, a major priority this year will be strengthening the conference SAACs. "I think we've already accomplished a lot, but you also have to realize that we're starting from ground zero again," she says.

Wells says conference and campus SAACs are a Division II priority, but that funding is an issue in many of the division's smaller members; she's also hoping that a greater effort can be made to enhance the quantity of community service performed by student-athletes. Some areas of potential legislation of particular interest to Division II are eligibility requirements, age limitation rules, contact days versus non-contact days in spring football and the exclusion of Pell grants from full grants-in-aid.

Division III is attempting to identify which committees will be dealing with student-welfare issues, according to Fernandez, in the hope that student-athletes will be able to have a presence at some of those meetings. One targeted by the Division III SAAC is the Committee on Competitive Safeguards and Medical Aspects of Sports.

Coley says that the new structure won't change the student-athletes' focus. "We were always a focused group," he says. "We picked issues that we felt were important and we wouldn't waste our time on the other things. Now, federation gives us an opportunity to focus on things that have to do with our division."

Adds Williard, "We're emphasizing to our new student-athletes that every time they look at an issue, they should go back and look at our mission statement: Does it protect the welfare of the student-athlete or does it promote opportunity? If so, it's a proposal in line with our goals. Sometimes that's really hard when you're in a certain sport and you have certain biases, but I think for the most part we've done a good job of creating that atmosphere."

Student-athletes are talking, but are administrators listening? Student-athletes all say they have sensed a huge shift in the attitude of administrators, but say some structural realities continue to hamper their ability to meet their goals.

Voting rights and representation on the management councils are clearly a major stumbling block. As Division II is currently set up, student-athletes have no representation on the management council and do not get a vote, but can make their views known to administrators during an annual summit, held this year during the same July weekend in Denver as the rest of the SAAC and management council meetings. On the whole, student-athletes felt the summit was a positive experience - particularly the pairing off of student-athletes with their conference representatives around the management council table. "I was particularly impressed by the format," O'Callaghan says.

Wells calls the summit "a compromise," with administrators suggesting the entire network of SAACs be developed before tinkering with the management council structure. "We thought they were very receptive to our ideas," Wells says. "We agreed that maybe a vote on the management council might have been a little premature. I believe the council thought the summit would be a better way to get a broad-based and diverse amount of input from student-athletes, and that if we had two-person representation like Division I, our voice would be diluted."

O'Callaghan, for one, feels that in light of the Prop 62 moratorium the comparison to Division I is rather apt. "We're just like Division I in the sense that the administrators are all there and we can talk to them about our concerns, but then they can vote however they want to anyway," he says. "Hopefully they listened to us in Denver. We met with the council on Sunday, and on Monday and Tuesday they went behind closed doors to vote on everything, and we'll find out if they took us seriously once we hear the results."

O'Callaghan says premature or not, gaining the vote would be a gratifying win for Division II student-athletes - even if it might not change anything tangible.

"The symbolism of the vote is probably what we're looking for," he concedes. "Raising our paddle, that would satisfy people. Even if we lost 40-1, we'd have gotten to say what we wanted to say and voted on what we felt."

Another student-athlete concern involves the makeup of committee representation. Division II administrators are trying to eliminate having post-graduate student-athletes on the national SAAC unless they currently attend a Division II graduate school. Division III representation is limited to undergraduates, although the Division III management council is considering allowing Division III graduate students to take part. Because of restructuring, older student-athletes in all divisions have been allowed to serve another one- or two-year term while the transition takes place, and student-athletes say this is vital to the health of the committees, even after the transition is complete.

"We think it is crucial to have post-grads on the committees, since it ensures greater diversity - and experience is a key to the committees' success," says O'Callaghan.

"New members have said they really value the leadership of the members who have been there for awhile," says Fernandez. "In the long run, hopefully the council will see it that way as well, because it's going to make their job easier if we can educate our own."

Fernandez is also concerned about the council's insistence that the same two student-athlete representatives attend all council meetings, just as the same conference representatives do. That, she says, can be difficult given student-athletes' obligations to their teams in season and to their academic work all the time. "Sometimes if there are issues pertaining to a specific sport, there may be a person on our SAAC who is affected by the legislation and can better represent that opinion," she adds.

If the student-athletes have a fundamental fear, it's that their views are being paid lip service. While all report being taken more seriously now than ever before, there are concerns that this summer's moratorium fight speaks volumes about administrators' real views of student-athlete welfare.

"I'll be the first to admit that Prop 62 is not a perfect piece of legislation," says Niland. "But a lot of student-athletes were relying on it. I think that was downplayed at the meeting. They said, 'Well, you're only talking about them working five hours a week.' Well, you know, five hours a week at even six dollars an hour, that's enough to put gas in your car. It makes a difference."

Coley scoffs at coaches' concerns about athletes not having time to work part-time jobs. "There are people who are able to work, who are adult enough to know if they have time to work or not," he says. In Coley's view, all this complaining about the potential negative side-effects of the legislation is not only counterproductive, it ignores two facts: student-athletes were not completely sold on Prop 62 as it was written, and have reacted to the mounting criticism by actively trying to answer coaches' and administrators' concerns.

"We weren't totally happy with Prop 62, but it was a step in the right direction," Coley says. "We think there are issues that need to be dealt with, and we've been presenting recommendations to the committee to try to get things worked out. But I don't think the proper way of dealing with this is to put it off for another year. What about those student-athletes who have already budgeted for this, who already have apartments set up. Now, 12 days before school starts, you tell them they can't work. What are they going to do?"

Mistrust. Fear. Apprehension. Frustration. These are all-too-common words used by student-athletes to describe a working relationship with administrators that by all reports has been mutually beneficial throughout the SAAC era. O'Callaghan, for example, believes administrators fear that student-athletes have come to the table prepared only to promote student-athlete welfare without regard for the health of the NCAA.

"I think there's an apprehension that student-athletes don't think about cost containment, but in our meetings that's a huge issue," says O'Callaghan. "If we don't think something is fiscally possible, we vote against it. I think we're a really responsible committee in all three divisions, and while we are out for the interest of student-athletes, we're also out for the interest of the NCAA and its institutions, because we know they need the money to survive."

While Niland admits the moratorium has colored her view, she says frustration and mistrust are givens in such a large, increasingly balkanized association.

"I can say it's frustrating for us, to sit in that room sometimes and feel like even though we share in this process, some people totally discount what we say," she says. "But then, there's a lot of money at stake. Feelings of mistrust are inherent in the NCAA because of the amount of money involved."

Other SAAC members remain more upbeat - particularly if, like Division III's Fernandez, they are in a SAAC that gets to vote.

"I wouldn't say it's a mistrust on the administrators' part, just that they may be afraid that we don't know the whole situation," Fernandez says. "They've seen the NCAA evolve over the years, and they want to be sure we don't make decisions that are hasty or that we're not educated about, because it is a very delicate process, and legislation evolves over a long period of time. Even we teach our young members that they're going to see some pieces of legislation be repeated, and they need to know the history behind it, why it's been defeated before, and not just think they can correct something at the bat of an eye. So I think administrators just want to make sure we respect the system and realize that there's a bigger picture."

One thing the events of the past six months make certain - student-athletes now have administrators' respect, at the very least the kind of respect that comes from power. This is "a healthy change," according to Fernandez.

"For the most part, when we got up at the convention you saw that people were listening, and people would approach us afterward and want to know more," she says. "To me, that's very encouraging."

"There were actually different groups lobbying us, trying to get us to support some issues in front of the convention, so you could see our power starting to grow," adds Coley.

Of course, as O'Callaghan notes, power commands respect, but it also engenders fear.

"At last year's convention we showed some of the real strength we can have in our voices, and I think we changed some votes last year, changed some people's opinions," he says. "I think some people are getting nervous. Maybe we have more of a voice than they want us to have."