A number of public school sports administrators (and an increasing number of parents) believe non-public schools have an edge come tournament time. AB's national survey finds marginal support for that claim.

Everybody knows that non-public schools, by whatever name they're called in communities across the United States - private, parochial, prep, independent, vocational-technical, "special" - have inherent competitive advantages over public schools. Their students tend to come from wealthier backgrounds, families who can afford membership at the finest fitness facilities and extras like private lessons. So, too, the schools are unconstrained by public schools' attendance boundaries, and can therefore draw student-athletes from all over.

Everybody knows these things, and many even suspect that there are other reasons for non-public schools' athletic prowess - like undue influence.

What no one really knows, however, is exactly how those advantages translate into championships. While aggrieved parents, students and coaches can cite anecdotal evidence - that is, their public school team lost in the final to a parochial school - no one even knows if non-public schools' advantages add up to more trophies.

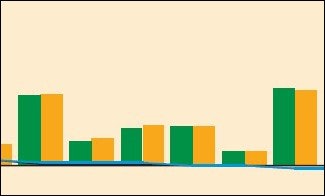

Until now. AB's survey of 43 of the 45 state activity associations whose public and non- public member schools compete head-to-head in state tournaments found that while non-public schools make up 13.1 percent of the schools, they won 18.4 percent of the championships in all sports during 1996-97 school year. As the state-by-state breakdowns show, non-public schools underperformed their numbers in only 13 of the 43 states.

Some other highlights of the breakdowns here and on the following pages:

• Almost all of the states where controversy has recently erupted over non-public schools performance have seen actual success by those schools. Ohio, which has had several referendums in recent years to establish separate state tournaments (see "Unfair Territory?" April 1994, p. 16). is sixth in the breakdown by state (14 percent non-public schools, 33 percent championships won). Florida, where a similar referendum was narrowly defeated two years ago, is 15th (29 percent non-public schools, 37 percent championships won). Missouri, where legislation to create separate championships was proposed but then languished in committee, is 10th (12 percent non-public schools, 25 percent championships won). Alabama, where a plan was floated to count parochial students as one-and-a-half students (see "11⁄2-Baked," June 1995, p. 17), is eighth (8.5 percent non-public schools, 25.5 percent championships won). And Tennessee, which voted in May 1996 to create separate tournaments beginning with the 1997-98 season, is 2nd (15 percent non-public schools, 54 percent championships won).

The only exception is Illinois (23rd), which created a task force to study the issue and, based on its recommendations, passed a plan to enforce attendance boundaries among its non-public school members (see "City Limits," October 1996, p. 16).

• Gender appears to have little if any effect on the public/non-public issue. Non-public schools' championship edge is attributable to boys' teams and girls' teams almost equally, although nonpublic schools' boys' soccer teams significantly outperformed their female counterparts (37 percent of titles to the girls' 25 percent) and non-public schools' boys' basketball teams held a modest advantage over the girls' teams (15 percent to 10.5 percent).

• Although most of the controversies nationwide have involved football and basketball championships, non-public schools' advantage is neither in the former (10 percent) nor the latter (13 percent), but primarily in soccer, tennis, swimming and volleyball.

• When multiple-class tournaments are broken down by classification, the data show a distinct advantage among smaller non-public schools. Different states break sports into different numbers of classifications; even within some states, some sports are broken into a dizzying range of tournament structures, making comparisons difficult. AB was unable to ascertain the percentage of non-public schools for each distinct classification in each sport in each state, so part of the variance in this area may be to a large extent attributable to a much greater number of small non-public schools.

Then again, maybe not. In West Virginia, for example, non-public schools make up 6.4 percent of the sample and won 7.9 percent of West Virginia Secondary School Activities Commission titles. As it happens, all nine of its non-public schools are in Class A (16.4 percent of Class A schools), but breaking down the state's data for Class A only shows that non-public schools won 17.6 percent of titles for which Class A schools were eligible - certainly consistent with the WVSSAC's overall figures.

In any event, non-public schools win 10 percent of the titles in the largest-class designation in every breakdown, but 25 percent of the championships in the smallest classifications. In six- and seven-class tournaments (and two eight-class tournaments omitted from this data), the lack of a similar trend line is likely due to the small sample.

It is hard to say whether last year's national differential between the percentage of non-public schools and the percentage of championships they won - 5.3 percent - is significant, statistically or otherwise. To be sure, Ohio's administrators and coaches - and athletes and their parents - would certainly argue strenuously that when one-seventh of the Ohio High School Athletic Association membership wins one-third of the titles, something is very wrong.

"It's not a level playing field," says one Ohio AD. "It's not that we don't want them to exist, it's just that they have such a vast territory to draw from. They get into some of these school districts and just decimate them."

But when pressed, most administrators can name just as many dominant public schools as private; indeed, Massillon, the Ohio public high school that dominated prep football there for years, was dogged by just as many rumors of recruiting and illicit booster dealings as was St. Ignatius, its parochial successor in the top spot.

As Richard Magarian, assistant executive director of the Rhode Island Interscholastic League, notes, Coventry High School (public) won its 15th championship in wrestling last year, while Mt. St. Charles Academy (private) won its 20th ice hockey title - both of which, he says, are national records.

"I'm sure there are lots of schools that wish Mt. St. Charles wasn't in the league," Magarian says. "It's the old story - parochials are fine as long as they're losing."

The two states with the greatest non-public school showing also happen to be two of the country's smallest - Hawaii and Delaware. In the former case, non-public schools won 16 of 21 titles last year - but 11 of those were won by one school, the Punahou School. Similarly, in Delaware, non-public schools won 15 of 28 titles last year, including eight by St. Mark's and three by all-male Salesianum.

Five or so years ago, a group of public school representatives demanded relief, and proposals to exclude private schools from state tournaments began to make the rounds. Robert Depew, executive director of the Delaware Secondary School Athletic Association, was asked by the DSSAA's board of directors to collect tournament data on the state's public, private and vocational-technical schools. (Vo-tech schools draw from an entire county, so their attendance area is considerably larger than the typical public school.) Depew found that far from non-public schools dominating all sports, certain schools dominated certain sports. (Salesianum is the state's top cross-country school of late, while St. Marks is the school to beat in wrestling and swimming/diving.)

"What we decided was that in a state this small, if you exclude private schools, you've taken some of the luster away from the state championship," Depew says. "I think everyone recognizes that some of these schools are very strong in certain sports, and to simply exclude them because they've been successful demeans the title of state champion."

Controversy has not been limited to states where non-public schools perform well. In spite of the New York Public High School Athletic Association's name, the group has 60 non-public school members - just under 4 percent of its 1,558 membership. Those schools last year won just under 6.5 percent of the championships - four titles out of 62. And yet, the NYPHSAA has been dealing with public/non-public problems for years now.

The NYPHSAA is subdivided into 11 sections, two of which (section VI, the Buffalo area, and section VIII, Nassau County on Long Island) have refused to admit any non-public schools, even though the other sections began doing so in the late 1970s. Both have recently been sued by private schools wanting to be members (the lion's share of Catholic schools against whom they can compete are in New York City), and both have prevailed. In the most high-profile case, Archbishop Walsh High School in Olean was denied admission to the association by the New York Court of Appeals. Walsh had argued its constitutional right to equal protection was violated, but the court ruled that Section VI had "legitimate" worries about Walsh having a competitive advantage because it can draw athletes from a wider area than the association's public schools.

Within the association, work is afoot to bring the entire organization in line with Section II (the Albany area), which from the outset wrote into its bylaws a provision granting it the right to place non-public schools in classifications as it sees fit (usually up one or two rungs). A referendum will be voted on this year that would add that rule to the umbrella organization's constitution.

All this, in a state where non-public schools won four titles last year?

"Is it a problem, or is it a perceived problem? In our state, it really is a perceived problem," says Sandra Scott, the NYPHSAA's executive director. "I don't believe we'll ever solve it, because as soon as you say 'non-public school,' people think, 'Oh, they have no boundaries,' and the next thing out of their mouth is that they recruit. I don't know how you fight that."

Scott says that in recent years outcry over non-public schools is an annual event, usually in basketball but last year in volleyball, and the driving force these days is public-school parents. Scott just attended a meeting of administrators and parents in the Lake Placid area, where there is but one non-public member school, and she reports 45 minutes were spent discussing people's concerns about this particular school.

"It's one that I know probably does as good a job as anybody in the state in terms of ethics and trying to abide by all our rules," she says. "But that doesn't matter - they still were talking about recruitment."

But DSSAA's Depew is not alone among administrators in thinking coaches aren't the problem.

"Coaches aren't trying to induce kids to attend a particular school for athletic reasons; those kinds of things aren't flagrant anymore," he says. "Most of it is by word of mouth among the players themselves. In a small state like Delaware, where say in basketball, the kids all play AAU basketball, go to summer camps and so on, those kids know who's going to have a good team. As of two years ago, we have a statewide school choice program in effect, so a kid can now apply to a school because it has four returning starters and all they need is a point guard. That's the kind of thing that happens now, and it's very difficult to control."

New York doesn't have school choice yet, but the problem there is the same. "Our problem is shopping by parents and kids," says Scott. "Let's face it, everybody's kid happens to be a blue-chip athlete, right? So they shop where they think their kid will develop into a blue-chip athlete. How are you going to control where people want to send their kids, when they know our rules better than our member schools and they're willing to go through all kinds of things - some where you would question whether they're in a gray area legally - just to get their kid into a particular school?"

This fall is Tennessee's first with a separate state tournament for non-public schools that offer student-athletes grants-in-aid. Thirty-three of the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association's 53 non-public school members opted to continue to offer financial assistance (they're now in Division II); the 20 others gave up that right (with current athletes grandfathered) to continue competing with the public school membership (now Division I).

Meanwhile, the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association is getting ready to go the other way. After the Wisconsin Independent School Athletic Association announced it had decided to close its doors in June 2000, the WIAA's members voted overwhelmingly in April to accept WISAA non-public schools into its membership.

The WIAA's executive director, Doug Chickering, says that during committee deliberations, nightmare stories out of Tennessee, Illinois, Missouri, Florida, Ohio and elsewhere were shared, and yet the final vote by WIAA membership was 90 percent to 10 in favor of admitting private schools. "The schools are not concerned," he says.

Three facts are bolstering their confidence, Chickering says: Wisconsin's school choice program subdues the attendance boundary issue, the WIAA's rule requiring athletes to live with their parents helps check movement from one side of the state to the other, and perhaps most important, the association has the opportunity to move gradually. The WIAA won't fully absorb WISAA schools until 2000-01 but has already taken 16 WISAA schools into regular season conference play - "It's a tremendous laboratory for us," says Chickering - and some of those schools have been competing in WIAA state tournaments for several years in four sports where WISAA doesn't offer tournaments (girls' golf, boys' and girls' swimming/diving and team hockey).

On the other hand, Tennessee's experience suggests that Wisconsin won't start feeling the heat until a private school wins the state football championship, even if it's the so-called "country club" sports where private schools could be expected to contend.

"You hardly ever hear about tennis and golf, but year in, year out, those sports and soccer were the ones that were dominated by private schools," says Gene Menees, a TSSAA assistant executive director. "But football led to people thinking about getting rid of the private schools, and a lot of it was directed at just one or two schools. You know, I'm being semi-facetious, but we've got some public schools that win a lot that people would like to see someplace else, too. It's amazing that it all boils down to who wins and who doesn't win."

Menees believes that most athletes want "to compete against the best athletes, regardless of which school they're in," but that's not even the saddest aspect of what's been lost in Tennessee.

"I think the split goes against a lot of things we're supposed to be teaching kids," he says. "Ideally, you want to teach that you should go out and play whoever you're playing, work hard, and if you win, you win. And if you lose, you work harder and come back the next game and play hard again. If you split because you can't, quote, 'beat somebody,' that's not good."