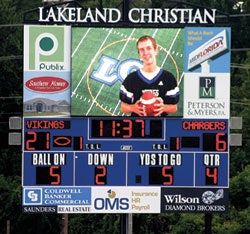

High-tech scoreboard and video display concepts are racking up points among high schools.

High schools everywhere and of every size are investing in the latest scoreboard, matrix and video display technology - particularly as that technology evolves and becomes more affordable. "The innovation and technology that used to be available only to professional teams or large colleges is now available to small schools," says Darren Garner, regional sales representative for Spectrum Scoreboards. "As recently as five years ago, only the big, powerhouse school districts had a video board."

With pixels spaced at 23 millimeters - a typical resolution range for indoor boards is 7 mm (sharpest, and most expensive) to 35 mm - the Pinedale video board combines programming flexibility and affordability, according to Brett Anderson, an electrical engineer at Colorado Time Systems. "In my opinion, 23 is the best compromise if you're going to use it for text and scoring and also video and graphics," Anderson says.

Indeed, spectators of today's high school, club-level and even recreational sports expect more than just the score. They want to see player headshots and profiles, real-time statistics and notices of upcoming events. "People are accustomed to this type of information," says Jeff Reeser, national sales manager for Fair-Play Scoreboards, adding of facility operators, "Everybody wants to be in the big leagues, and this gives them the ability to do so many things other than just have that score up there."

This feature becomes particularly handy when soliciting sponsorship dollars to help pay for scoreboard upgrades, Garner continues. "In many smaller towns that don't have the big sponsors willing to pay $20,000 to $30,000 to a school district for a 10-year deal, enough mom-and-pop shops can be found that will pay $400 or $500 a game for a couple of games," he says. "If you can put them up there electronically, you can generate a lot more revenue because you have a lot more potential advertisers to go after."

"There are about 35 or 40 advertising opportunities during a standard high school football game," says Scott Moore, vice president of sales and marketing for scoreboard manufacturer Nevco. "We have high schools that have put video displays on their football fields and paid for them within three years." A matrix is just as convenient when taking sponsors' names off the board. Says Reeser, "Let's say somebody's not paying you. You just take them out of the rotation. Stop playing their file until they pay up. It's that easy."

Some numeric scoreboards come equipped with diffuser panels, thus presenting cleaner, less-pixilated LED digits. Others offer light-sensitive brightness controls that ensure high visibility. One numeric board model introduced to the market last summer automatically changes its numeral colors to coincide with lead changes, or to indicate that the clock is running or stopped. "Not every school can afford to buy a matrix or video display," says Dan Bierschbach, vice president of sports products for scoreboard and display manufacturer Daktronics. "It's going to take a few years before they're as common as numeric scoreboards. So for those that don't have that kind of budget, this is something that adds a little more pizzazz."

Yet, an increasing number of schools are finding the money to invest in upgraded scoreboard technology, particularly if they see that a rival school has already done so. "People see them and say, 'That's what they have? We need to do something better,' " Reeser says. "And it's not necessarily the school officials who say it. It's the parents and the booster groups. People are proud."

One advantage to the dual-role approach is the ability to customize matrix templates to fit each sport that the board will serve. These schools no longer have to send maintenance personnel up ladders to manually change out caption placards that read "DOWN," "YARDS TO GO" and "BALL ON," or squeeze track results onto a scoreboard designed to display only football information. Matrix technology offers a blank canvas on which the formatting for game-, match- or meet-specific information can be created.

Once the game is on, matrix board operation is as straightforward as opening files on a personal computer. Operators can replace scoring information to allow the entire board to briefly display other text or graphics files through a series of simple mouse clicks. "Most of the time they're going to have their scoreboard information up. But let's say a time out is called; they can click to another file to show something besides the scoreboard - a 'Go Team!' message, for example," Reeser says.

Operators also have the option of downsizing the scoring information to make room on the matrix for messages posted simultaneously. Says Reeser, "They might take a section of that board - the left third, say - and create a zone where the scoreboard information will sit. Then they can run upcoming game information on the other two-thirds."

The configuration possibilities are only limited by the size of the matrix hardware. "You can go too small, and then you can't get all your information up there," Reeser says. "You're dealing with only so many pixels or points of light that you can control."

And while a monochrome matrix may be able to display still images and animation in more than 250 shades of light, Anderson advises against overlaying imagery and text. "If you start putting video up there and try to put text over it, it becomes a little bit busy and difficult to read," he says. "If you're doing the scoring for an event, you really want people to be able to read what's up there. That's the information they want."

Wireless control has become commonplace with traditional scoreboards, but the sheer amount of data that feeds a matrix doesn't allow for it. Fiber-optic cabling is preferred. "Wireless technology has advanced tremendously in the past five to seven years," says Nevco's Moore. "It's much more reliable, has far less interference and is able to transmit more data now than at any time in the past. When you simply put up scoring and timing, the wireless equipment isn't a problem. But when you start to transmit prerecorded video, a hardwire connection becomes more important."

Moreover, the internal time-keeping capabilities of most personal computers may not allow for operation of a matrix-displayed game clock, particularly one being used for basketball, where a split second can determine whether or not a late basket is counted. Therefore, a standard game clock control is often set up to interface with matrix software, which then translates each tick to the display without delay. Says Moore, "In today's environment of instant replay and tenths of a second, it's incredibly important that all equipment throughout the facility - from the shot clocks to the end-of-period lights to the scoreboard to the matrix - is integrated and consistent." The scoreboard control and the computer continue to communicate even when crowd-prompt graphics momentarily take over the entire screen during live action, ensuring that the game clock is accurate upon its reappearance.

Getting a feel for how to control the scoreboard - and, by extension, the crowd - comes fairly easily to novice operators, according to Reeser, who once worked the matrix board at an Arena Football League game. "You can really rev up the crowd," he says. "Obviously, the action on the field is what's doing it, but amazingly there are enough people who watch the board who will react to a suggestion. Once an operator gets a feel for it, it can really make a difference."

Will liquid crystal display technology similar to what is seen in TV screens, calculator windows and computer monitors, and already used in some portable scoreboard models, be subject to large-scale display application in the sports world? Purveyors of LED systems claim that LCD technology to date is expensive, fragile and inferior in terms of its poor viewing angles and potential glare issues.

Will modular displays, a descendant of the concert tour industry, gain widespread acceptance as a means of giving end users double bang for their investment buck by allowing a matrix serving football to be disassembled and reassembled indoors in time for basketball season? Bierschbach has already seen the latter scenario unfold in his company's home state of South Dakota. "Economically, it pencils out pretty well on the front end, but then emotion starts to come into it," he says. "During football season, volleyball is going on inside, and those coaches and players start to think, 'Well, maybe we should have one, too.' A lot of times the schools just end up wanting a dedicated board in both places." Other high schools have maximized revenue potential by shuttling displays between their football fields and nearby highways. Says Terry Phipps, president of Tulsa, Okla.-based First Team Outdoor Video, "Instead of just five homes games, sponsors get a whole year of advertising exposure."

Will scoreboard software continue to evolve in ways that maximize a display's efficiency and effectiveness? Statistics management software employed by a dozen Major League Baseball teams last season sifts through available data and recommends to operators relevant stats for display during the at-hand game situation.

The clock appears to be ticking, but there's still plenty of time left for numeric scoreboards, which have survived in some form for seven decades and counting. "All that area between the home team's score and visiting team's score on a traditional scoreboard is basically painted aluminum, whereas on a matrix board it's all LEDs and electronics," Garner says. "Well, LEDs and electronics have come down in cost, but not so much as to offset the fact that we can still build a traditional scoreboard with a sheet metal cabinet for less than we can a full matrix board."

In the meantime, manufacturers are happy to watch schools within the same geographic region, or even teams within the same school, try to keep up with the Joneses. "Keeping up with the Joneses is where it's at in Texas. And really that's where it's at everywhere," says Reeser. "It's a great thing for us, and for all the other scoreboard manufacturers."

That's when diocese technology director Ken Collura, inspired by projected hymn lyrics during a school mass, approached athletic director Dave Thompson with an idea to replace the antiquated gymnasium scoreboard hardware with a computer-generated scoreboard projection system. Now in its second year of use, the system features four ceiling-mounted projectors that beam custom-designed scoreboard templates to all corners of the gym during basketball games and volleyball and wrestling matches. "You walk into every other high school gym in the nation when there's nothing going on, and there's a scoreboard sitting there with its lights off," says Thompson. "Well, in ours there are just plain walls."

For now, at least, Bishop Hartley fans are treated to projected headshots during player introductions and trips to the free-throw line, accompanied by the individual's up-to-date game statistics. "It's pretty cool," says Thompson, who gathers photos from visiting teams in advance of games so that their players get equal time on the wall. "Virtually anything that can be put on a computer, we can throw up there."

Thompson also works the phones during Bishop Hartley games in search of "scores of interest," which are updated on the projection board. Between 10 and 15 advertisements per event also appear, helping pay for the system, which was built in partnership (and at an undisclosed discount) with software provider and patent-holder Crosswinds Consulting. "We got through that first year without a single failure," Collura says of the system's debut last season. "That is amazing."

"They way I look at it, we have two pieces of equipment - the computer and the projector - that have been around for a long time," Thompson says. "We're just using them in a novel application."