A Georgia lawmaker takes steps to help prevent fatalities

Last February, Chattahoochee High School in Alpharetta became the second Georgia school within a fourteen-hour period to lose a student-athlete to undetected heart problems. Less than a year later, in an effort to prevent future tragedies, State Rep. Mark Burkhalter is trying to convince the Georgia Legislature to pass a law creating a standardized health and physical form for student-athletes in the state. The bill would also develop a statewide education program - a videotaped presentation is likely - for students, parents, coaches, trainers and private physicians encouraging proper use of the new form.

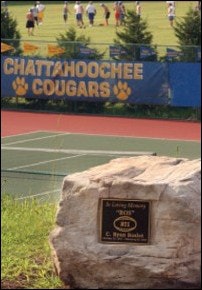

The "Ryan Boslet Bill" is named in honor of the 17-year-old football player who collapsed during a running drill at an offseason workout in Chattahoochee's gym. He later died from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a genetic heart disease resulting in a thickening of the heart muscle that typically goes undetected - but that can be detected with proper screening, doctors say.

"The goal is to prevent tragedies," Burkhalter says about the bill, which will be introduced next month. "We want coaches, parents, trainers and students to think about the questions on the form and about what giving an incomplete or inaccurate answer can mean. The hope, then, is that when physicians notice something out of the ordinary, like an irregular heartbeat, they will do some additional testing and not just sign off on the form. This has the potential to be a model piece of legislation."

Right now, all high school student-athletes in Georgia must present proof of a physical examination prior to competing, but critics say the exams often aren't thorough enough.

Boslet was one of three Georgia student-athletes who died of undetected heart defects during the 2002-03 school year. Fourteen hours before Boslet's death, Derrick Plankenhorn, a member of the Southeast Bulloch High School track team in Brooklet, died eight minutes after dropping to the ground during a cool-down lap. Doctors later determined no exam would have detected Plankenhorn's fatal heart problem. But one certainly could have saved Shai Owens. Owens, a 16-year-old honor student at Cedar Grove High School in Ellenwood, collapsed at a cross country meet in August 2002 and, like Boslet, died of a heart condition that had gone undetected since birth.

The debate over safety in high school sports is nothing new, but never before has the debate focused so heavily on the heart. Of the 15 high school football deaths during the 2002 season, more than half were linked to heart-related causes, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injuries at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

At least 43 states have some sort of standardized medical-history form for student-athletes, Burkhalter says. But the state high school association, not the state government, usually oversees use of those forms. The Ryan Boslet Bill would likely give Georgia one of the country's most encompassing laws regarding the proper care of high school student-athletes' hearts and the rest of their bodies. If the bill becomes law, it will take effect July 1, allowing school officials (on whom the onus will fall to ensure local physicians use the form) ample time to distribute the mandated forms in their communities. Support has come from all sides that have a stake in this issue - including coaches, athletic trainers, physicians and the Georgia High School Association. "It's very gratifying to know you've got people coming to you to ask how they can help," Burkhalter says.

More power to him, says Charles Breithaupt, athletic director for Texas' University Interscholastic League. Last year, the UIL created a uniform medical-history form that is the only one student-athletes in that state can use. (Discussions have recently surfaced about extending the standardized form to participants in other extracurricular activities - namely, members of marching bands.)

Forms must also now be filled out by student-athletes, their parents and their doctors every year - not every other year, as was previously the case. A major component of an athletic director's job in Texas, Breithaupt says, is getting parents to take the paperwork seriously. "Parents get deluged with forms," he says. "Many times, it's just the kids putting them in front of the parents, who sign them, and that's that. You would think convincing parents that they should tell the truth about their child's health wouldn't be a problem. But some parents give their kids steroids, too. That's the mentality we're up against."

Breithaupt says that one universal medical-history form has streamlined the physical-examination process in Texas and given doctors a better opportunity to discover conditions in student-athletes such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - among the most common causes of sudden cardiac death in young athletes because of the added physical exertion on the heart during exercise. According to A Heart For Sports, a nonprofit organization based in Yorba Linda, Calif., that offers free onsite heart screenings (or echocardiograms) for high school and college student-athletes, many victims experience no symptoms. Others, however, may experience shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, light-headedness or blackouts.

The high cost of echocardiograms (usually between $800 and $1,500 per test) has prevented many school districts from offering screenings for student-athletes - another option under consideration for widespread adoption in Georgia. But Arnold Fenrich, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children's Hospital in Houston and a member of the UIL's Medical Advisory Committee, claims that echocardiograms aren't 100 percent accurate. "If you were to do an echocardiogram on everybody, you'd only be able to find one in three people who are at risk," Fenrich says. "The other two-thirds will have a normal echocardiogram but still may be at risk of sudden cardiac death. It gives kids and their families a false sense of security. To me, that's worse than not screening anybody at all. If you're going to provide student-athletes with the best chance of survival, have a means of resuscitating them available, like an automated external defibrillator. That way, these kids may still be alive and then they can go off for more thorough examinations."

Fenrich's opinion was enough to keep the UIL from going ahead with a corporate-sponsored program to provide free echocardiogram screenings for all Texas student-athletes. Instead, the UIL has helped boost the prevalence of AEDs in the schools.

"If schools are screening, or want to screen, I think that's great," Fenrich says. "I wouldn't want them to stop. But they still need an AED, because they're not going to be able to detect everyone."

Lawmakers and school administrators across the country are heeding the need for AEDs. Illinois, New York and Pennsylvania have already passed laws mandating AEDs in public schools, for example, and similar legislation is pending in 15 other states. And in July, President Bush signed the Automatic Defibrillation in Adam's Memory Act, which authorizes the establishment of an information clearinghouse to increase access to AEDs in schools via educational programs, legal advice and other methods. The act is based on the work of Project ADAM ™ , a nonprofit Wisconsin organization developed in late 1999 in cooperation with Children's Hospital of Wisconsin after 17-year-old Whitefish Bay High School basketball player Adam Lemmel died on the court from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. (See "Matters of the Heart," January 2003, p. 28.)

While the government has yet to determine how to fund the act or who will oversee it, Project ADAM officials hope Wisconsin gets the nod as the site of the national clearinghouse and are in the process of creating a model for how the clearinghouse would work.

Meanwhile, Georgia medical officials, in the wake of that state's first sudden cardiac death of the 2003-04 school year, are reportedly keen on becoming one of Project ADAM's first state affiliates. On Sept. 11, 13-year-old Emil Gadjev, a student at Atlanta's Sutton Middle School, collapsed and died after a soccer practice. Sutton did not have an AED available. Of the three heart-related deaths at Georgia high schools last year, only Boslet's occurred where a defibrillator was readily available, but no one present knew how to use it.

Gadjev's death lends even greater significance and urgency to the Ryan Boslet Bill. Among its chief supporters will be Chattahoochee High students not only interested in learning how the legislative process works but also intent on preventing future deaths of their peers across the state.

Burkhalter, who has previously taught classes at the school, plans to employ the same strategy with students as he did last year, when members of Chattahoochee's advanced government class helped secure passage of an environmental bill offering incentives to developers who protect Georgia's waterways. This time, though, Burkhalter expects participation will be open to all students in the school. They will be expected to testify in front of various legislative committees and subcommittees, debate amendment strategies and lobby for votes.

"There's a lot of passion in that school for Ryan," Burkhalter says. "These are kids who can get up and say, 'My friend died as a result of not having had a thorough examination. It has affected my life and always will.' "