In April, the head women's soccer coach at the University of Houston stated in an email to a parent that he was implementing several program changes to prevent injuries caused by physical punishment after 12 of his players experienced rhabdomyolysis. Diego Bocanegra went so far as to admit that one change involved removing mention of physical punishment from the team's weight room manual, leading some to question why such language was written policy in the first place.

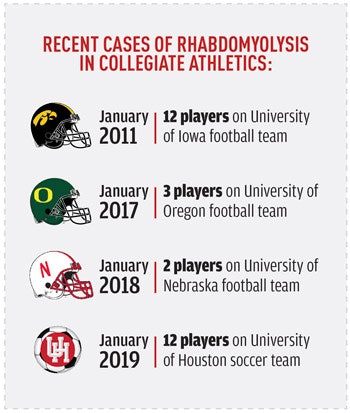

Many student-athletes in various sports have suffered rhabdomyolysis, a serious syndrome triggered by extreme exertion that results in dead muscle fibers being released into the bloodstream. It is the all-too-common result of coaches mandating extreme workouts and pushing student-athletes to participate in activities that are not reasonably safe. At its worst, rhabdomyolysis can lead to complications such as renal (kidney) failure or heatstroke, and even death.

Not only are extreme workouts bad practice from the standpoint of student-athlete safety, they can lead to institutional liability, as illustrated in Lee v. La. Bd. of Trs. for State Colls., 2017 CA 1431 (La. Ct. App. Mar. 13, 2019).

Tiger Mix tragedy

Jacobee Lee accepted a full basketball scholarship to Grambling State University, with his career to begin with the Fall 2009 semester. Basketball players were required to report to GSU on Aug. 9 that year, but Lee arrived on Aug. 12. Upon arrival, Lee attended a brief basketball team meeting where school registration, upcoming practices and general information were discussed. At the meeting, the team decided to have an unofficial weightlifting workout session on Aug. 14.

Members of the coaching staff were present for the weightlifting session, which lasted approximately 45 minutes and involved each player "maxing out" on various exercises. After the weightlifting concluded, eight team members, including Lee, were told by assistant basketball coach Stephen Portland that they had to run approximately four miles (closer to four and a half miles) around the university campus. This run was required of all team members who reported late to campus for the fall semester.

The run, which had also been held the previous year, was called the Tiger Mix. The players were given about one half hour to rest and hydrate between the weightlifting session and the run and were told that they had to finish the run within 40 minutes or do the run again on another day. The student-athletes were also told that the penalty for refusing to run was possible suspension from the team.

Although the temperature on Aug. 14, 2009, was approximately 91 degrees, with a heat index greater than 100 degrees, and an outdoor football practice had been cancelled because of the heat, the Tiger Mix run still occurred. During the Tiger Mix, players did not have any access to fluids, and there were no aid stations available on the course of the run. Further, there were no athletic trainers present, nor were any other medical staff available. In fact, none of the GSU athletics medical personnel were even aware that the run was taking place. Coach Portland did follow the runners in a golf cart, but he did not provide them with any assistance.

The student-athletes participating in the run finished with varying levels of "success." The first student-athlete to finish, Rydell Harris, provided assistance to teammate Henry White, who was having difficulty. Harris helped White inside the gym, where White then passed out. White was breathing heavily and was unresponsive. Another player went to look for the athletic trainer and a coach for help.

At some point thereafter, Lee finished the run and entered the gym. He got some water, sat down against a wall, and passed out. He awoke briefly, saw White slumped over, and passed out again. Like White, Lee was unresponsive.

Teammates tried to cool White and Lee down with water and ice. Eventually, additional coaches and the university athletic trainer arrived, and began to render aid to both White and Lee. Initially, only one ambulance was summoned for White, but ultimately both White and Lee were transported by ambulance to the emergency room at Northern Louisiana Medical Center in Ruston. Laboratory tests revealed elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) levels and volume depletion related to heat exposure, low potassium levels (hypokalemia), and resting sinus bradycardia. Specifically regarding the CPK levels, a normal range is between 35 and the low 200s. Lee's CPK level was 651 when he arrived at the hospital following the Tiger Mix.

Lee was admitted to the hospital and aggressively hydrated. While in the hospital, Lee shared a room with White. Although there was a drape separating the two beds, Lee could hear the difficulty White was having breathing. Lee was discharged on Aug. 16 with diagnoses of heatstroke and mild rhabdomyolysis.

White died on Aug. 26, 2009, as a result of severe heatstroke.

After his discharge from the hospital, Lee went back to Grambling, but did not rejoin the basketball team. Although he was released to regular activities by his cardiologist, Lee stated that he was not able to return to competitive basketball because his CPK level would rise upon physical exertion. Lee remained at Grambling State for the fall semester, but did poorly academically.

In February 2010, Lee played in an independent basketball tournament. A few days later, on Feb. 8, 2010, Lee was admitted to the hospital with fever, a skin disorder and a urinary tract infection. Testing revealed that Lee had a CPK level of 7955 (recall that the normal range is between 35 and the low 200s). After a consultation with a rheumatologist, Lee was determined to be acutely ill, potentially suffering acute renal failure. The rheumatologist also believed that Lee's persistent elevated CPK level was caused by the heatstroke he suffered as a result of the Tiger Mix in 2009. The rheumatologist stated that the 2009 injury was not minimal and that the heatstroke caused Lee to suffer permanent irreversible damage to his skeletal muscle and permanent exercise intolerance. According to the rheumatologist, Lee would no longer be likely to play college or professional basketball, and Lee's future job opportunities would be limited, as well. The rheumatologist further stated that employment such as heavy manual labor or the military were no longer viable options.

Lasting damage

On Aug. 6, 2010, Lee filed a Petition for Damages against the Board of Supervisors for the University of Louisiana System and GSU (collectively Grambling) for the personal injuries and damages he suffered as a result of Grambling's negligent actions or inactions. On March 23, 2016, following a seven-day trial, the jury found Grambling at fault for Lee's injuries and awarded him $2,529,229 in damages.

The trial included testimony from Thomas Stallworth, an expert in the field of strength and conditioning and GSU's director of strength and conditioning from 2008 to 2012. Stallworth testified that it was his opinion that the Tiger Mix was a blatant disregard for athletic rules and regulations and NCAA policies. He stated that pursuant to NCAA bylaws, structured activities are not allowed before the first day of academics in a school year, and given that the Tiger Mix was mandatory, a violation likely occurred.

Further, Stallworth stated that no one discussed the Tiger Mix with him and, had he been made aware of it, he would have advised that it was "a bad idea." He testified that athletes — especially freshman athletes — want to please their coaches and will do whatever is asked of them, regardless of whether they are conditioned or acclimated to the heat. He stated that running for approximately four and a half miles for any college athlete is an extensive amount of volume on a physiological system, which can be damaging to the central nervous system and to body function.

Stallworth also testified as to hydration, heatstroke and the 1-to-3 work-to-rest ratio between physical activities — that is, for every minute of activity there should be three minutes of time off — based on academic and professional standards. Stallworth stated that the 20-to-30-minute break between the nearly one-hour workout session and the disciplinary run in this matter was not enough time to allow the players to adequately recover.

In appealing the judgment of the trial court, the defendants did not challenge the finding of liability, but instead raised evidentiary issues and asserted that the amount of damages awarded was excessive. Lee also appealed, contending that the trial court erred in vacating the jury's award for future economic losses as being subject to the State's limitation on general damages.

The 2019 decision by the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Louisiana adjudicated issues related to trial procedure and the ultimate damage award. While the judge did reduce the damages to $659,227.50, she maintained Lee's damage award for lost earning capacity, stating that "considering the evidence related to [Lee's] injuries and their effect on his life, we find that the evidence clearly supports the jury's finding that [Lee] has suffered and will continue to suffer from the injuries he sustained as a result of the Tiger Mix."

Extreme becomes common

Although Lee suffered his injuries almost a decade ago, his ultimate award of damages was only affirmed by the courts this year. Further, and more disturbing, coaches and athletic programs have not learned — or have willfully ignored — the potentially harmful, even deadly, impacts of excessive physical activity, especially when combined with the impacts of heat.

The death of White and the sustained harm suffered by Lee should have been a clear example that student-athletes are exposed to significant physical risk when coaches implement extreme practice measures. Yet, using extreme physical activity as punishment is a coaching strategy that remains commonplace, despite the incidence rate of harm to student-athletes.

In January, the University of Oregon, members of its coaching staff, and the NCAA were sued by a former player who suffered rhabdomyolysis in 2017 as the result of workouts involving up to an hour of continuous push-ups and up-downs. The lawsuit alleges that the workouts were designed to be punishing, done in unison, and whenever a player faltered, vomited or fainted, his teammates were immediately punished with additional repetitions.

The plaintiff in the lawsuit filed against the University of Oregon stated that a key goal of the lawsuit is to force the NCAA to ban punishing and abusive workouts, a step that is clearly necessary. However, that specific action by the NCAA is unlikely, as is the ceased use of these workouts by coaches. Unfortunately, previous lawsuits, such as Lee's, including significant damage awards, as well as the death and continued harm and suffering of student-athletes, has not had an impact thus far.

Ten years is a long time to learn the lessons of the Lee case and others. Sadly, those lessons have yet to be learned.

Kristi Schoepfer-Bochicchio is chair of the Physical Education and Sports Performance Department at Winthrop University and executive director of the Sport & Recreation Law Association.

This article originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Athletic Business with the title "College pays for coach who used exertion as punishment." Athletic Business is a free magazine for professionals in the athletic, fitness and recreation industry. Click here to subscribe.