Youths Are Lining Up to Partake in UC-Berkeley's Skateboard Camps

It's called the Strawberry Canyon Skate Facility today, but for 15 years the sloping roof of a University of California parking structure was known among outlaw skateboarding locals as the Berkeley Banks. Backdrop to magazine articles and skateboard videos, the area more often saw its board-packing infiltrators chased away by campus police. Now, thanks to a two-year-old program run by the UC-Berkeley Department of Intercollegiate Athletics and Recreational Sports, some of the skaters who once received tickets for riding the roof collect paychecks for imparting their skateboard knowledge in a designated 10,000-square-foot area there - and a new generation of students is lining up to learn.

Targeting children ages 8 to 16, the Strawberry Canyon Skateboard Camps represent perhaps the most atypical youth camp offered on a campus known for its recreational diversity. (Cal boasts 25 different sports and recreation summer camps as part of its Strawberry Canyon Youth Programs.) In fact, its organizers believe it may be the only one of its kind sponsored by a college campus in the entire country. "There may be some camps running skateboard-type programs, but I haven't been able to find any that are running it at the caliber that we are," says Jennifer Selke, training and development director for the youth sport component of Cal athletics. "I equate it to the difference between an open recreation swim and Red Cross swim lessons."

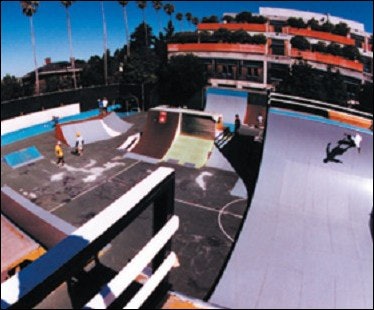

Whereas other programs may provide a facility at which students and community youths can skate unsupervised, Cal officials believe they have taken campus skateboarding to another level. The university spent more than $35,000 to spice up the old Berkeley Banks - famous for the rounded transitions at the base of the parking structure's cement walls - with plastic-covered plywood ramps, pyramids and half-pipes. It then scoured the local skate community for potential program leaders, each of whom faced a rigorous interview process that included reference checks. Once hired, these individuals are expected to pass on more than their grasp of given maneuvers - everything from turning to dropping in on ramps. Says Mike Weinberger, the university's director of recreational sports, "We actually have instructors who have developed a curriculum to teach safety and etiquette, along with the physical tricks."

Such structure in a freewheeling activity like skateboarding catches some first-time campers off-guard. "It's different from what the kids are expecting when they come in," Selke admits. "They want to do tricks. They want to learn the flashy stuff. Our philosophy is that you really can't learn that until you have the basics down." Lesson one, for example, covers how to fall - and every camper must learn it. But instead of letting the strict curriculum serve as a potential turnoff, Selke views it as the perfect opportunity to introduce the concept of mastery orientation to young athletes who may participate in a variety of sports.

"The skateboard world is very different philosophically from the more traditional sports world," she says. "There's a shift now in trying to get youth sports to be more mastery-oriented. We train the coaches in our summer camp programs to help kids understand that sports isn't about winning; it's not about doing better than the next team. It's about improving your own skills. The youth sports world has gotten away from that idea, but the interesting thing that I've found is that skateboard instructors come in with it. They already have a mastery-orientation philosophy."

According to Selke, a common sight during any of a two-week camp's 10 three-hour sessions is the sharing of skateboard knowledge among participants: "One kid will be working on a trick, and the other kids encourage him." Conspicuous by its absence is the clique culture common to many organized youth sports, even among camp participants representing diverse social backgrounds. Some kids may play youth soccer and Little League baseball, as well as skateboard, while others may view skateboarding as their lone athletic outlet - their only means of fitting in. "They all come together with one purpose, and it's about getting better at skateboarding," Selke says. "We just don't see a lot of the same issues - such as the teasing - that we see in other programs, because the philosophy is so different."

Moreover, camp instructors emphasize the relationship between skateboard basics and real-life skills. For example, awareness of conditions and the presence of others while skating is easily related to awareness in life. The same goes for balance. Says Selke, "That's the unique thing: The kids get the skills component, but they also get a life-skills side that I think youth sports is always trying to promote in terms of character building. It's sort of a multilevel curriculum."

Pent-up demand for such an outlet for youths not drawn to traditional sports (and traditional summer sports camps led by varsity head coaches) was evident from the skateboard program's inception two years ago, when five times as many would-be registrants were turned away as could be assigned one of 300 open slots (cost per person: $350). Long waiting lists emerged again last year, and a new priority-registration policy for summer 2002 campers will begin this month. Inspired by the priority-arena-seating model employed by the Cal athletic department, campus recreation officials decided to offer early registration times for children whose parents donate at least $100 to a new fund-raising campaign called Bear Backer Youth. That money in turn will help fund camp scholarships for children without the financial resources to attend otherwise. "We don't have basketball arenas and seats, but we do have these very popular camps with waiting lists," Weinberger says. "For the first five or six weeks, we'll only take signups from donors. I've never seen that on the rec side before."

Also new this year is a full-day camp option for elite skaters, some of whom have been on board through the program's first two years, complementing the half-day camps, private lessons and supervised birthday parties already offered.

It's that kind of nontraditional thinking that has turned the collective of Cal's youth recreation camps, which includes a variety of outdoors offerings, into a $2 million-a-year enterprise, with the bulk of the revenue generated during the university's 10-week "down time" from midJune through August. "It's pretty intense," says Weinberger. "The reason we started to take on youth programming so heavily is that we weren't getting a lot of campus funds. Youth programs are wonderful, because they're educational, they bring kids to campus and they serve the outreach mission of the university - but also because people are willing to spend on their kids, more so than they are on themselves. They will pay for their kids to go to a camp before they sign up for their own personal membership to work out."

Skateboarding has provided Weinberger's department with more than healthy revenue figures, however. It has managed to raise an understanding of skate culture in board-wary Berkeley. Selke is now considered a resource for city officials on the subject of skateboarding, and Cal has proactively promoted the sport's growth in the community. One outreach effort entailed a visit to a community day school for children expelled from the local school system. "It was a great equalizer," Selke says. "A lot of the kids who were expelled were minority students who come out of a more traditional sports background. A lot of them play basketball, and skateboarding really sort of put them all on the same level."

It's the same type of awareness preached atop the parking structure. "Being a public institution in Berkeley, where we take up a significant part of the town, we really need to make sure that we're supporting the people around us and not just making money," Selke says. "Skateboarding is great from both sides: It does provide income, but it also provides a real avenue for us in the community."