Refining Equipment-Management Procedures

As the season opener begins, a university baseball team takes the field, clad in outdated, torn and stained uniforms. A few players emerge in apparel used by the team a decade ago. When play begins, the umpire warns the players to be cautious when approaching second base, as there is a large tear in the bag. Then, partway through the game, an athlete chooses one of two bats and manages to hit the ball out of the yard for a home run. A benchwarmer needs to be sent to fetch it, as it's the last ball in stock.

While this may not be a likely scenario, it is an example of what could happen without a solid equipment management system in place. Administrators must have specific procedures for taking inventory of their equipment, assessing their needs for the upcoming season and purchasing gear by finding the best balance between quality and cost, often by working with manufacturers and dealers to receive discounts and the best value possible.

In many cases, whether at the high school or college levels, administrators must work with limited budgets to acquire equipment for their department. Because of this, many schools in the past have worked out deals with sporting goods manufacturers ranging from schoolwide contracts to small promotional deals. Manufacturers are thereby able to advertise their product to committed athletes as well as the general viewing public, and school administrators are able to save money through discounts, bulk rates and free equipment. In the case of school-wide packages at major universities, in which universities commit to one manufacturer for all their sports equipment, the money gained is substantial enough to dramatically increase the budget in other areas, such as recruiting and travel. Moreover, buying decisions are reduced to one manufacturer, eliminating bidding from most of the purchasing process, and limiting customer-service calls to one contact. However, these arrangements are becoming less and less profitable for the manufacturers, who for that reason are pulling away from them.

"The all-school deals are not going to be as common as they once were," says Jeff Boss, athletic equipment manager at Louisiana State University. "I think you're going to see a lot more of what I call cherry-picking, where manufacturers deal with just the programs they want to deal with at your school and then leave the rest alone."

Terry Schlatter, director of materials management for the University of Wisconsin, expects that school-wide deals, which began to gain ground during the past decade, will slowly die out within the next five years. Wisconsin currently has a school-wide deal with Reebok, which is entering the final year of its five-year contract this fall, and Schlatter can't be sure to what extent it will be renewed, if at all.

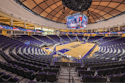

Since deals are often based on how much income a manufacturer feels it can gain through exposure and retail sales, the size of the contract often depends on the school's marketability. According to Schlatter, Wisconsin has a great advantage in that not only is it a Big Ten university with a number of highly successful athletic programs in recent years, but the state's climate means that retail sales will include spring, summer, fall and winter gear. Since the university draws big home crowds and travels to large-market areas for road games, it can often negotiate an even better deal. But some sacrifices come with that bargain.

"Sometimes when you're dealing exclusively with one company, it may try to influence you on what your uniforms are going to look like, because what athletes and coaches are wearing on the sidelines is what the company wants to take to the retail line," says Schlatter. "So it is going to try to change models on a yearly basis so it helps increase retail sales."

There are other reasons for caution, too. An exclusive contract can drastically limit a school's purchasing flexibility. Moreover, in some contracts, a certain amount of equipment may be provided for free, but any amount beyond that would need to be purchased at the regular price. If a university cannot negotiate to buy the additional product at reduced prices, the final price may be higher than it would be had the university used a traditional bidding process. If contracts are primarily signed to attain a maximum amount of money or apparel for coaches, manufacturers can make a profit through the athletes' equipment. So, as with any contract, administrators must be careful to investigate the details.

More often than not, high schools and smaller colleges and universities have to rely on scaled-down promotional deals. Like school-wide contracts, such deals are also becoming less prevalent in recent years, but many manufacturers continue to approach schools with offers ranging from "buy one, get one free" to outfitting an entire travel squad with uniforms if the team buys the company's shoes. At Cornell University, for example, several individual sports programs have worked out separate deals with manufacturers. Generally, these agreements are mutually beneficial, but administrators must still be careful to choose manufacturers with quality products and good service.

"We really encourage a promotional situation as long as it doesn't compromise the quality of the equipment," says Dale Strauf, head equipment manager and physical education instructor at Cornell. "We don't want to be locked into a situation where it would compromise quality just for the sake of saving money."

As promotional deals and school-wide contracts lose their luster, colleges, universities and high schools are returning to traditional bidding for planning and purchasing. As with any purchasing procedure, the process begins by taking careful inventory of what the school already has. This means more than simply counting the number of uniforms and balls in the equipment room. All equipment must be separated into categories - new, good and fair. Only the equipment that is usable should be taken into consideration when assessing needs. Generally, an inventory should be taken immediately after each sports season ends. If it is possible to begin making purchasing decisions at this time, it will be the only inventory necessary. Otherwise, some schools opt to do a second inventory just before ordering to make sure that none of the equipment has been damaged or stolen since the initial inventory.

To curb theft, LSU's Boss limits the amount of practice gear available to each player, but rewards athletes for taking care of their equipment by letting them keep their practice shirts, shorts and sweats. He simply orders new practice apparel each year, knowing it is usually too worn after one season anyway. Game equipment is much easier to track, since specific sizes and amounts are ordered for and assigned to each player. Boss attaches a number to the outside of each player's apparel to identify gear so that athletes will be responsible for their equipment, and will serve as enforcers against theft.

Once an inventory is completed, a needs assessment must be performed. Often, uniform sizes for returning athletes are logged, but sizing for incoming freshmen is largely guesswork. So, unless he is able to get athletes sized during campus recruiting visits, Boss will base purchasing decisions for incoming freshmen on the equipment needs of their predecessors. If three wide receivers are graduating, he will use their information to help decide the needs of their would-be replacements. Those players who are returning have the benefit of discussing their needs directly with Boss.

"We sit down with each of the players and try to forecast needs for the next year," Boss says. "With shoes, for example, it's really good to spend five minutes with each athlete and talk about what he or she wants to wear for practices and games, and how many pairs he or she will need for each."

The resulting needs assessment is then combined with requests made by the coaches, and then compared against the inventory. At times, compromises can be made. At Cornell, for example, basketballs that have become too worn for athletics may get rotated to physical education and then recreation, and athletic shoes too worn for competition may become practice shoes. Eventually, a wish list is created that will be formed into a bid request. Generally, a certain percentage is added on to the projected needs for apparel to cover fluctuations in the number of athletes from year to year, as well as depletion of stock through damage or theft. While Cornell goes high with about 20 percent overage, most schools will add between 8 and 15 percent.

Bid requests must use specific language to ensure that the desired products are the basis for the bid. Since many states require public universities to accept the lowest bid, unless there are provable concerns about safety or quality, it is essential to be sure that a bidder hasn't substituted a lesser product to try to produce the lowest bid. This may mean spelling out that bids can only be for this year's model or, for example, for a 100 percent cotton, ash-colored practice T-shirt with the school's name in 1-inch crimson block lettering. In some cases, league rules may make it necessary to specify certain types or brands of equipment. High schools, for example, may need to state that balls must have the National Federation of State High School Associations' authenticating mark on them. Bid requests can also help scope out bulk discounts. The quantity can be left as a range, or a request can be specifically worded for particular quantities - 100, 200, 500 and 1,000, for example - to see if any quantity breaks show up in the pricing.

Also key is the timing of the bid request. In an effort to get their bookings in advance, many manufacturers offer early-ordering discounts. Generally, for fall sports that means ordering in February, winter sports in April and spring sports in June. While that may seem difficult since many schools don't end their fiscal year until June or July, it is common at many schools. Many manufacturers will take the order and hold shipping and invoicing until the summer. So in many cases, nothing is actually paid until after the budget is approved.

"If you have the ability to purchase before the end of the fiscal year, and you can take advantage of early-order purchasing, you can save anywhere from 15 to 20 percent," says Strauf. "By the time we get the equipment and they bill us, it's actually very close to the end of June, in time to prepare the equipment for issue. In a lot of cases, we don't actually pay anything until after the budget has been approved."

Deciding from which companies bids will be solicited is often based on personal experience, word of mouth and knowledge of the company's products. Some schools will submit to any company with which they've had contact. Others, especially those that are required to accept the lowest bid, will restrict the submission to those manufacturers that have proven themselves in terms of quality products, good service, timely delivery and other factors.

"We make the decision based upon the experience that we've had dealing with a company and the quality of the product that we have had firsthand or that we observe from surrounding schools," says Bill Faflick, director of athletics for the Wichita (Kan.) Public Schools. "We don't just buy it because it's the cheapest. We also buy it so that it will last. We don't have the money to replace it two or three years down the road."

Once bids are returned, someone must check through them to be sure no improper substitutions have been made. Then, when the lowest bid has been found, administrators must compare it against the budget and be prepared to prioritize needs. The equipment manager and coach work together to pare down the list of requested equipment until the bid fits within the available budget. Some schools have a system like Faflick's, in which each sport is on a rotation to receive a significant purchase at least every seven years. The rest of the prioritization is set by the essentials required.

"In my mind, safety issues come straight to the top, and then the game essentials," Faflick says. "You have to have balls and you have to pay for officials. All of those expenses are given. When you know you don't have enough to do what you want to do, you have to prioritize, and you have to get input from the coaches, and help them understand what your limitations are."

Even so, many high schools and colleges have a hard time meeting even minimum requirements. Although many pass older equipment down from athletics to physical education to recreation programs, or from varsity to junior varsity to freshman teams, the budget still can't cover the schools' needs. At Lowell High School in San Francisco, the entire athletic department is given an annual budget of about $8,000, which when divided among the sports is pretty tight. Baseball, for example, gets $400. Athletic director and baseball coach John Donohue therefore recently led an initiative to develop a nonprofit fundraising group called the Lowell Sports Foundation. While athletes have for years raised supplemental funds by selling pizzas or helping with community events, this nonprofit group has the potential to raise a more substantial amount of money. Donohue estimates the department would need $15,000 to $20,000, along with its $8,000 budget, to adequately cover entry fees, officials' pay and other necessities for the year. Some of this funding could mean the difference between writing a purchase order to accept a bid and having to hold off another year or longer to purchase new equipment.

It's all a complicated balancing act. Many tricks and procedures can be learned, however, through further education in equipment management, available through certification from the Athletic Equipment Managers Association. Today, an equipment manager's position is made even more sticky by the increasing number of NCAA and high school rules restricting equipment allowable for play, as well as the rising influence of computers for data-keeping and inventory purposes. Both of these elements, as well as information regarding anatomy, physiology, biomechanics and physics, are expected to come into play as certification requirements for athletic equipment managers are revised and approved by the AEMA this fall. The certification, which has been offered for nearly a decade, provides specialized education in all of the equipment manager's roles, including purchasing; fitting equipment and clothing; maintenance of equipment; administration and organization; management, professional relations and education; and accountability for equipment.

Guided by this education and experience, equipment managers must carefully administer their budgets, making sure to get the best value for their dollar by negotiating deals with manufacturers and developing specialized bidding processes, so that when their baseball team steps onto the field, they'll have the best equipment the budget can buy.