Advocates For Safe Glass seeks changes in athletic facilities and schools

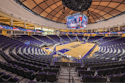

Jarred Abel, a junior at the University of Oregon, was playing pickup basketball in a gym at the school's recreation center on Jan. 28, 2001, when he ran into a door. Abel's left hand punched through the door's wired-glass window and was severely lacerated (see photos), leading to multiple surgeries and permanent injuries.

Abel's lawsuit against two glass manufacturers and the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), which oversees glass standards, has yet to go to trial. But in the meantime, Abel's father, Greg, through the nonprofit group he founded (Advocates for Safe Glass), has scored several victories that have forever changed the specification of windows and doors in athletic facilities and schools.

The safety of wired glass in these applications has long been a matter of dispute. Wired glass was for many years the only fire-rated glazing product available - indeed, at temperatures as high as 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit, wired glass holds together even when hit with water sprayed from a fire hose, preventing flames and hot gases from spreading to adjoining spaces.

However, wired glass is much less impact-resistant than standard glass, a fact that has been obscured by a common misperception - that the wire mesh sandwiched in the product somehow reinforces its impact strength. It actually weakens it, so much so that the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission would not classify it as a safety glazing material when it established federal standards for such products (16 CFR 1201) back in 1977.

Because wired glass was then the only fire-rated glazing that met other building code requirements, the CPSC exempted the product from federal regulation for the next two and a half years, purportedly to give the industry an opportunity to produce a wired, yet impact-resistant product. What happened instead was a bureaucratic standoff - wired-glass manufacturers challenged the exemption termination date, and the CPSC backed down, amending the exemption to keep it open-ended. Advocates for Safe Glass charges that wired-glass manufacturers have since that time actively hindered the process of code review by intimidating code bodies, engaged in deceptive marketing practices and stacked consensus standard committees with their operatives.

For 25 years, wired glass only had to meet what Advocates for Safe Glass sees as a substandard impact standard - ANSI Z97.1, in which the pane must withstand a force of 100 foot-pounds, essentially the impact of a small child. All other types of glass approved for use in assembly-type buildings are held to a higher standard, CPSC 16 CFR 1201, in which the pane must withstand 400 foot-pounds, similar to the impact of a fast-moving, full-grown adult.

Throughout the 1990s, regular drumbeats were heard questioning the use of traditional wired glass in areas deemed "hazardous" by the CPSC and ANSI - school hallways, gymnasiums, staircases and so on. In 1991, IRC Structures News (a publication of the National Council of Canada) printed an article pointing out that wired glass "is for fire, not for strength," and specifying a number of technologically advanced - this was 13 years ago, remember - replacement products. In 1995, Doors and Hardware magazine published an article written by Jerry Razwick of Kirkland, Wash.-based distributor Technical Glass Products that did the same. Another glass supplier, Bill O'Keeffe (president of San Francisco-based O'Keeffe's Inc.), was an outspoken enough critic of wired glass that he sued the CPSC in 1994 for failing to remove the wired-glass exemption. He lost. (A 2002 profile of O'Keeffe in USGlass magazine called him the "Wired Warrior," even as some continue to question his motives as a supplier of non-wired products.)

"Wired Warrior" is a moniker that would better suit Greg Abel, whose tireless efforts as an advocate galvanized support for change. Abel tracked injuries on his group's web site (www.safeglass.org), made the rounds of glass industry trade shows and eventually enlisted the help of his congressional delegation to change Oregon's state building code, ending the wired-glass exemption in that state's public assembly buildings. This May, he scored his most impressive victory to date when the International Code Council (an organization working to standardize building codes across the United States) voted to bar the use of wired glass in all building structures in areas subject to human impact - including schools and athletic facilities. The ICC's action effectively ended the "temporary" exemption from federal regulation that the wired glass industry had enjoyed since 1977.

"The vote required a two-thirds majority to pass, and it overruled the committee action," Abel says. "When the moderator announced the code change, the entire audience, which was made up of code officials from around the United States, stood up and applauded. They've been beat up for so many years by these special interest groups, and finally they said enough was enough. It was huge."

Although the International Building Code for 2003 has been adopted and is being enforced by 44 states and the Department of Defense, Abel says there's more work to do. As he notes, neither the ICC's nor the state of Oregon's action requires building owners to retrofit existing structures. However, a number of school districts in Oregon responded immediately to their state's building code change by replacing wired glass with a new generation of fire-rated and impact-resistant products, or by applying a vinyl-film product that holds existing wired-glass panes in place on impact. Although Technical Glass Products' Razwick cautions against use of a surface-applied product in schools - "If kids scratch their initials into it, it could be a continuing maintenance issue," he says - Abel calls vinyl film "a simple and affordable solution."

While Abel's three-year odyssey from local businessman to expert on the international glass trade might seem to stretch the boundaries of credulity, he sees his new role as a logical continuation of his various careers. A former law-enforcement officer, Abel owns Resources for Literacy, a maker of educational products for special-needs children.

"When my son looked up at me from the emergency room table as he was being prepped for surgery and said, 'Dad, just remember, everything happens for a reason,' I had no idea what lay ahead," Abel says. "I think that, as a parent, you have a responsibility not only to your own children but to all children."