They are confined playing fields with near-limitless functionality. Since their rise to prominence on college campuses two decades ago, multipurpose activity courts have maintained their go-to status among both recreation facility designers and end-users looking to pack the most programming punch into one self-contained indoor space.

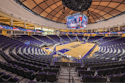

University of New Haven MAC photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates — Click here to see more

University of New Haven MAC photo courtesy of Sasaki Associates — Click here to see more

"They haven't gone away," says Erik Kocher, principal/owner at Hastings+Chivetta Architects in St. Louis. "If anything, the ones we've done recently are getting a little bit more sophisticated. And it's not just us; a lot of architects are doing this. MACs are now being developed with their own entry, so they can be used for all kinds of special events without users having to go through the front desk of the rec center. They have their own bathrooms. We just did one that has its own catering kitchen, because they're becoming more of a campus resource."

There are the resident sports, of course — basketball, volleyball, badminton, soccer, futsal, dodgeball, broomball, Wiffle® ball, field hockey, floor hockey, inline hockey, tennis, laser tag, group exercise. The list is unrivaled among recreational sports facilities. Kocher recalls strolling through a rec center whose MAC was in the middle of hosting a Quidditch match.

"You're trying to attract as many students as possible to participate in different activities," says Chris Sgarzi, sports principal at Sasaki Associates in Boston. "And you're always trying to come up with programs that might appeal to different groups. So you're always going to get your pick-up basketball folks, but if you can come up with other activities, then you have a better chance of higher utilization and engaging more students."

Adds Jack Patton, a principal with RDG Planning & Design in Des Moines, Iowa, "MACs are still a viable part of collegiate rec programming. They provide a 'Yeah, we can do that' response."

BIG MACS With dasher systems and enough space, a school can effectively double its multipurpose recreation programming. (Photos courtesy of Hastings+Chivetta Architects) — Click here to see more

BIG MACS With dasher systems and enough space, a school can effectively double its multipurpose recreation programming. (Photos courtesy of Hastings+Chivetta Architects) — Click here to see more

SIZE DOESN'T MATTER

Individual game rules may be tweaked in transition to the indoor space (think soccer without sidelines), and the same can be said about MAC design in general. No set standards exist for what one should look like, but the mind's eye image remains one of a rectangular playing surface consisting of synthetic flooring surrounded by a dasher board system or masonry walls (or a combination of the two) with the curved corners of a hockey rink.

When the room's own walls serve as the court's boundaries, one can expect to see masonry block deeply recessed at goal boxes, team benches and scorer's areas — though how deeply recessed is up to the designer — and the flat masonry units (typically 15 inches long) turned to create the gradual radius of the room's corners. "There's no real standard necessarily for even the goal boxes," says Kocher, "because you're potentially playing so many kinds of different recreational sports."

Scoreboards and fire alarm strobes are best positioned out of reach and caged; door hinges and handles should be hidden or door jams eliminated altogether; and other room components such as thermostats and fire extinguishers relegated to the bench area or an adjacent corridor to create as flush a vertical surface as possible. For this reason, dasher systems designed for ice hockey represent the biggest evolution in MAC design. "The dasher board system really gives you the most pure surface, because it's designed to be continuous," Sgarzi says. "When you turn a room into a MAC, you can try to alleviate some things, but you still likely have to deal with doors and columns."

Then the question becomes how much of a masonry-walled MAC gets padded. The backs of recessed goal boxes often are to deaden balls, and the goal's corners can be, too. "I haven't seen a MAC entirely padded," says Sgarzi, "but if you have any protrusion or corners, you would pad those."

MAC dimensions are typically extrapolated from the 84-by-50-foot layout of a recreational basketball court, with 10 feet of run-out room all the way around creating a minimum playing surface measuring 104 feet by 70 feet. That said, nothing is written that says any given MAC can't be larger. In fact, the room size can be effectively doubled to house two dasher-enclosed courts side-by-side, perhaps separated by Plexiglas and netting. In this configuration, it can further be specified that the side dasher sections running parallel to each other be removable and their floor sleeves capped to create one mega dodgeball court, for example, or a temporary concert hall.

Ceiling heights of 24 to 30 feet are similar to those of a typical gym. Suspended basketball goals are common, and suspended volleyball stanchions are possible, if enough clearance exists for the two sports' equipment to coexist. Suspended jogging tracks can encircle part or all of a MAC, though it's recommended that netting or some other barrier be installed to protect joggers from projectiles or that the entire track be elevated from the recreation facility's second level to its third.

ON BOARDS Some MACs combine dashers and walls as court boundaries, but less common is the MAC with a hardwood surface. (Photos Courtesy of RDG Planning & Design) — Click here to see more

ON BOARDS Some MACs combine dashers and walls as court boundaries, but less common is the MAC with a hardwood surface. (Photos Courtesy of RDG Planning & Design) — Click here to see more

FLOORING ALTERNATIVES

While basketball may dictate the general dimensions of a MAC, it's not necessarily the space's top draw. And that's likely just fine with facility operators, who often specify a MAC in large part to relieve their more-traditional multicourt hardwood gymnasium space of multipurpose pressures. Facility operators may want to limit the line markings on a hardwood floor, as well as the wear and tear that additional sports such as floor hockey bring to the surface.

With basketball purists drawn to the traditional gym's hardwood, MACs are often specified with a lower-maintenance surface, either a monolithic synthetic flooring or modular tiles. "There's frequently an 'ah ha' moment," Patton says. "We'll see a client with a large wood-floor gymnasium and maybe some desire to have a resilient floor in a gymnasium-like environment, but they aren't going to do a gym of half of each. So they cross the boundary and say, 'Maybe a MAC is another additional viable space. Let's put an alternative floor in there.' "

Tiles are the preferred surface for volleyball and can accommodate inline hockey, as well. Meanwhile, a poured synthetic floor's formulation and thickness can be customized depending on the desired performance criteria. A multipurpose synthetic floor designed to accommodate inline hockey, for example, will feature a firmer-than-normal topcoat.

Less common are MACs with hardwood courts, which accommodate a range of sports but present more maintenance concerns than the alternatives, and MACs with synthetic turf, which essentially serve indoor soccer, lacrosse, field hockey and tennis, but little else. In fact, public and private recreation facilities are considered the nearly exclusive domain of turfed MACs — if the term MAC even applies. "There's a market there for soccer leagues," Sgarzi says. "The uses that you might see on a college campus involve trying to create different types of activities."

Kocher, for one, would like to see the list of possible activities lengthened. "I've had nobody take us up on this, but I've been interested in finding someone who wanted to really treat it more like a convention space, where you have just a concrete floor and maybe add the dasher boards, and seasonally you might have tile floor in there," he says. " But I've always envisioned somebody having three weeks of sand volleyball tournaments and doing it indoors by bringing in sand on this concrete floor. Then you take it out, clean it up and put the tile back down."

But why stop there? "You could literally bring in and put up temporarily an above-ground pool and have a fishing tournament in it, if you really wanted to do something that crazy," Kocher says. "I'm always looking for those kinds of different approaches to recreation."

So are campus recreation professionals who continue to see the multifunctional value of MACs. "It does come up in every conversation we have about a new rec center," Sgarzi says. "Most of the ones that have done some research are aware of them and they're asking about them. If they haven't, we'll bring it up and just show them photos and bring it to the conversation."

Like the corners of the MACs pictured, the conversation often takes a predictable turn, according to Sgarzi. "Most do want them, and it goes back to that point about engagement of as many participants with different activities as possible."

This article originally appeared in the September 2014 issue of Athletic Business with the headline, "We Can Do That."