The most impressive stats shared with fans visiting War Memorial Arena in Syracuse, N.Y., on any given night last season weren't displayed on the scoreboard, but rather on a monitor just inside the turnstiles.

"People could walk into War Memorial and see the difference from the previous year," says Joe Casper, president of Syracuse-based Ephesus Lighting, which in 2012 made the 7,000-seat local rink the first major sports venue anywhere in the United States to be illuminated with an LED light designed specifically for sports application. "It was shown on a TV screen how much energy we're saving in that building."

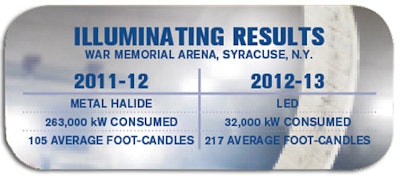

And it's a lot. Built in 1951, War Memorial prior to last season was still operating under the shadowy hum of metal halide light fixtures that consumed 263,000 kilowatts of power annually. During the 2012-13 season, the first with LED lights, the power draw was reduced 87 percent to 32,000 kilowatts. Moreover, the amount of light hitting the ice improved from an average of 105 foot-candles to 217.

"We were not only a very dimly lit building, but the lights would frequently go out," says Syracuse Crunch owner Howard Dolgon. "We had blackouts during hockey games, and then these lights would take up to a half hour to heat up and go back on — not unlike what happened during the Super Bowl in New Orleans. We don't have that issue anymore."

That's because the most immediately apparent advantage of the solid-state semiconductor technology is the fact that LED fixtures reach full brightness roughly 1.5 seconds after being turned on. A glowing list of selling points follows: There's the energy savings, the fewer fixtures required, the reduced maintenance costs, the lesser impact on air conditioning and ice conditions. It all adds up to savings that Dolgon says approaches six figures.

For the Crunch, there's also an entertainment value. Lights can be programmed for effect during pregame introductions. The goalie can be isolated in light, lights can chase around the arena and, new for this season, the lights are able to turn the ice the exact same color blue as players' jerseys. "The lights give us the ability to do things we couldn't do before," Dolgon says. "They've become a promotional tool for us."

CLOUD CONTROL LED lighting fixtures at the Dee Events Center are divided into nine completely dimmable zones. (Photo courtesy of Weber State University )

CLOUD CONTROL LED lighting fixtures at the Dee Events Center are divided into nine completely dimmable zones. (Photo courtesy of Weber State University )

LED lighting is well on its way to becoming the standard in the AHL, with the league's teams in Binghamton, Bridgeport, Rockford and Toronto making the switch from high-intensity-discharge metal halide, a technology notorious for its rapid degradation of light quality and frequent (perhaps annual) replacement of bulbs. This summer, Casper demonstrated his product at the AHL's invitation during the league's board of governors meeting. "The Chicago guys came running after me and said, 'We want that lighting system,' " Casper says. "Teams are using it as a way to get more people to fill the seats. We not only do the lighting, we do entertainment."

But it's all business once Casper's LED lights are programmed to do what they're specifically designed to do - illuminate sporting events. Each arena's system is modeled before installation and then tested on-site. For hockey, vertical and horizontal light measurements are taken in 48 locations on the ice. On game day, preset lighting specs can be changed from one sport to another with the push of a button. "Every single light is individually controlled" wirelessly using a radio-frequency band, Casper says. "We can go ahead and say, 'Adjust that light down to 60 percent output,' or, 'Take it all the way up to 100 percent output.' If there are dark spots or light spots, we adjust all the lights specifically so there is complete uniformity, even if there is different light absorption in different areas of the arena."

This is particularly true of a basketball court, which may have greatly contrasting colors in its design. Jake Cain, energy and sustainability manager at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah, began the process of converting the school's 10,000-seat basketball arena to LED last year by purchasing a single fixture and pointing it at the Dee Events Center floor from 60 feet above.

Oblivious to what the former Lockheed Martin engineers at Ephesus were up to in Syracuse, Cain nonetheless felt confident in his own lighting expertise to experiment. "I could actually start from scratch and say, 'Okay, how much light do I need on the floor? Where do I need it? How do I get it?' " Cain says. "And then I backed up and said, 'Okay, what are some of the options for the efficiency I want in the light, the longevity, weight, ampacity, all the other stuff? What kind of wires have I got up there? What I want is a really high-output directional LED light.' "

"Directional" is the key word, according to Cain. "Most light, as with an HID or an incandescent, you have a little thing that glows really bright and it shoots light off in all directions," he says. "You have all these reflectors and cans to reflect the light where you want it. Well, by the time you get all that light reflected around, you lose about a third of it, if not more. If it's a dusty fixture, you can lose up to half your light before it even leaves the fixture. LEDs actually produce light to shoot in a certain direction, so you don't really lose any light as you're trying to put it where you want it."

Cain discovered Albeo Technologies, at the time a Colorado-based maker of high-bay warehouse lighting that has since been absorbed by General Electric. But even the original manufacturers hadn't envisioned the sports-application potential of their product. "We bought the light and started installing it, and about halfway through installing it, that's when Albeo called me and said, 'We hear you're doing something pretty crazy with our light. We want to find out about it.' "

TANGIBLE BENEFITS

Since installing 80 fixtures in the Dee Center's ringed "cloud" rigging arrangement — with 20 providing uplighting of the arena dome and 60 illuminating the court, bowl and even emergency exits (no more costly halogen or incandescent bulbs on the backup generators) — it seems everyone wants to find out about Weber State's LED lighting. The Dallas Cowboys called, as did two-dozen schools nationwide. "Locally, I've had pretty much every university in Utah at least want to come and take a look at it," Cain says. "They say, 'Wow, once we get the money put together, we want to do the same thing. ' "

Why wouldn't they? Power consumed by the "cloud" has been cut by 70 percent, saving the school roughly $25,000 annually, and the rigging's overall weight was reduced by approximately 2,000 pounds. Annual lamp replacement has been eliminated, since each LED light's estimated lifespan is 150,000 to 160,000 hours, Cain says, "which for us is like 30 years." All this for a $200,000 capital investment, $156,000 of which is being trimmed from the university's overall power bill over time thanks to utility company incentives. (Casper says 50 percent rebates on installations of his Energy Star-certified lights are common.)

"I did some different analyses on how this project panned out," Cain says. "If I did purely just the energy savings, it was about an eight-year ROI. If I threw in energy and maintenance, it was like five. If I threw in the utility incentive, now I'm down to about a one- to two-year range for it to pay for itself."

There are non-monetary, but no-less-tangible benefits to the conversion, too. Because they operate with a ballast, metal halide lights emit what Cain calls "a horrendous 60-hertz buzz."

"The Dee Events Center is now perfectly quiet," he says, adding that's what players noticed most. "If you've got one guy in there shooting a basketball hoop, all you can hear is the ball bouncing."

Camera operators sensed something else - improved high-definition broadcast capability resulting from the bright, white light provided by the LEDs. Says Cain, "By using the type of light we did and the high foot-candles, when you put an HD camera on one of these guys, you're watching every bead of sweat fall off his face as he's getting ready to shoot that free throw."

Eighteen Crunch games were televised live last season, according to Dolgon, who noticed the difference. "From a fan perspective, it's much easier to watch the game, not only in person, but the game translates much better on television," he says.

Those fans who do make the trip to War Memorial Arena in Syracuse will see not only a monitor extolling the venue's green virtues, but a space transformed from its dark ages. "It's unbelievable the difference. You don't recognize the building," Dolgon says, adding that it's only a matter of time before AHL parent organizations start making the switch to LEDs. "When you get into buildings that have 200 or 250 events a year, you're not going to save $100,000 a year. You're going to save double or triple that.

"Pretty soon, you're going to see every arena have these lights. They have to. They're energy-efficient. They don't emit a lot of heat. They're great for the players, they're great for the fans, and they're great for us promotionally. And they save money. Why wouldn't you have them?"

BRIGHT ASIDES

LED lighting not only illuminates playing surfaces for competition, it eliminates the need for auxiliary lighting equipment in the arena setting.

Emergency lighting over exits has long been the domain of incandescent or halogen bulbs that can strike instantly under the power of a back-up generator. The instant-on capability of LEDs allows select fixtures within an arena seating bowl configuration to be pointed at exits instead. "Halogen lights are very expensive to run," says Ephesus Lighting president Joe Casper. "They consume roughly 900 watts of power, but we can do it with a 150-watt light — the same 150-watt light we're using to light the seating bowl."

Spotlighting for player introductions can be eliminated through the wireless control of individual LED fixtures. Certain areas of the playing surface can be isolated in light, even as the rest of the arena goes dark. As Syracuse Crunch senior vice president Vance Lederman told WSYR-TV as War Memorial Arena was debuting its LED lighting last year, "It's really going to enhance the fan experience. The stuff we'll be able to do in terms of lighting, spotlighting players. You can spotlight players without even a spotlight."

Believe it or not, darkening a sports arena is an expensive proposition — at least in those arenas with metal halide lighting, which is nearly all of them. Because high-intensity-discharge metal halide lights take up to 30 minutes to strike on, they cannot be turned off during player introductions. "I'm looking at the Energy Solutions Arena here in Utah where the Utah Jazz play," says Weber State University energy and sustainability manager Jake Cain. "In order to get the lights dark and introduce the players, they don't turn the lights off - they have a million-dollar shutter system that puts shutters over the lights to block them. And that's true of almost all arenas. Most NBA arenas have a million-dollar shutter system. Think about that. Somebody installs a $200,000, $300,000, $400,000 HID lighting system and puts in a million-dollar shutter system so they can do introductions. They could have installed a $200,000, $300,000 LED system that turns the lights on and off without the shutters and uses a third of the energy." - P.S.