On Nov. 23, the University of California football team hosted Stanford in the 105th playing of what is known on both campuses as the Big Game. Some 2,500 miles to the east, an equally big game took place that same Saturday afternoon between Ohio State and visiting Michigan.

While showcasing similar rivalries in terms of tradition, the games illustrated significantly different approaches to ticket sales. That's because Cal charged fans wishing to gain admission to the Stanford game nearly twice what a typical Bears ticket costs, just as it has been doing for years. Ohio State, meanwhile, placed no such premium on its marquee matchup of the season, though some would argue it's high time it did.

"Ohio State should double the Ohio State-Michigan price," says sports economist Dan Rascher, a Cal alum and director of the sports management program at the University of San Francisco. "That game is a national brand. It's the biggest game of big-game weekend."

"That is a ticket that we could virtually assign any price and there would be people who would pay it," says Richelle Simonson, Ohio State's associate athletic director for tickets and event management, who describes as "obnoxious" the high ticket demand created by the Michigan game. "But that's not what we want to do. We don't want to gouge people."

That said, Ohio State has joined legions of other major colleges and universities (and a growing number of professional franchises, particularly in MLB and the NHL) by at least contemplating the concept of variable ticket pricing, through which premium ticket prices are charged for select individual games. Michigan, for one, broke internal precedent by bumping up the price of Ohio State tickets by $5 in each of three seating categories prior to the 2001 meeting of the two schools at Michigan Stadium. "I looked at what other schools were charging for premium games," says Marty Bodnar, Michigan's ticket director. "I created a chart, and a $5 increase was certainly within an acceptable range. We didn't have any problem selling out."

Sold-out games, which drive up the street value of tickets, are ripe for variable ticket pricing, according to Rascher. "It really makes sense to raise the price," he says. "The evidence for that, of course, is that we see a lot of ticket scalping at certain games. Fans are essentially paying that higher price anyway; it might as well go to the athletic department."

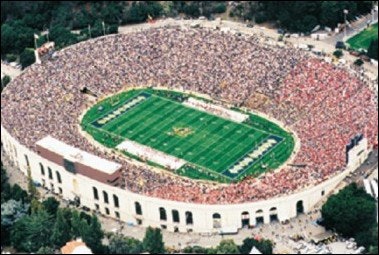

But sellouts aren't absolutely necessary for variable ticket pricing to make sense (Cal drew 67,500 fans to 75,000-seat Memorial Stadium for the 2000 Big Game), nor are they the only indicator that future price hikes may be in order. For example, baseball's Colorado Rockies assign four different dollar values to certain seats at Coors Field, based on several factors that are mixed and matched. They include the opposing team (divisional rivals represent the best draw), the day of the week (weekends are more attractive than weeknights), the month of the season (summertime games typically bring pleasant weather and increased numbers of school-aged fans), and special attractions (such as Opening Day and games featuring fireworks displays). Hockey's Boston Bruins, meanwhile, have taken variable ticket pricing a step further this season by dropping game-day ticket prices by the hour in an attempt to fill the FleetCenter more regularly with large walk-up crowds.

Colleges may take similar, if less complex, approaches. It's not uncommon for schools to charge one price for nonconference games and another for conference games. Other considerations when pricing single-game tickets may include a matchup's attendance history, the preseason prospectus of that particular opponent and whether a special event, such as homecoming or the honoring of a head coach, is tied to the game in question.

Cal not only researches the ticket prices that other Pac-10 schools are charging, it considers how the Bears stack up in the league standings. "It doesn't make sense to have the top ticket prices if we're not the top team in the conference," says Jonathan Evans, Cal's director of ticketing. Evans also compares Cal athletic events with other sports and entertainment options in the San Francisco Bay area, a marketplace that includes the NFL's 49ers and Raiders and MLB's Giants and A's. Combined with input from key athletic department personnel and athletic board members, this analysis results in a standard football ticket price of $27, which jumps to $35 for Bears games against USC and UCLA (which visit Berkeley in alternating years), and $50 for the Big Game.

This academic year marks the first in which Cal has used variable ticket pricing for men's basketball, with marquee games against USC, UCLA, Arizona, Stanford and Oregon priced at $28. Every other ticket is $22. "We're playing Howard early in the season," Evans says. "Last year, a Howard game early in the season would have been the exact same price as Stanford or Arizona later in the season. People probably thought that was a great deal. Now there's a price difference between the two, but I think most people grasp the concept and understand that those later games are more valuable, and therefore it costs more to attend."

The University of Tennessee - a school that has never seriously discussed variable ticket pricing, according to Dara Worrell, assistant athletic director for ticketing - often finds itself designated as a marquee opponent when its football and men's and women's basketball teams hit the road. "When we travel with the women's basketball team, the ticket for our game will be the home team's most expensive of the year," says Worrell, adding that the Vols receive no percentage of the increased income. "It's kind of aggravating when you see a school that normally sells a $5 ticket, and then all of a sudden it's $15 when we come to town. They know what they're doing to get $15 from our fans or people in their own community who are coming to the Tennessee game, but we wouldn't do it to our home fans."

Tennessee will go so far as to limit promotions at home games it is confident will sell out 25,000-seat Thompson Boling Arena. Offers of half-priced tickets with the purchase of regular single-game tickets are standard throughout the season and contribute to average home crowds in excess of 17,000, but they are suspended for marquee matchups involving Connecticut (which visits Knoxville every other season) and Vanderbilt, Worrell says.

Of course, whenever schools raise their ticket prices, they assume the risk of fan backlash. Price certain games too high, and people may choose to stay home. Fans may even shun the lower-priced games, deeming them inferior. "One of the things that could happen is you start to devalue certain games or certain types of games," Simonson says. "There's the chance that people could become confused with exactly what it is that you're doing and how much they're being charged."

Rascher suggests explaining the increases as a necessary means to build new facilities, remain competitive or simply stay afloat. "One of the keys for all of these college athletic departments is going to be accounting for and managing the perception of the fans, while at the same time trying to set the prices in a way that maximizes revenue," he says.

According to Rascher, maximum revenue is most often realized when games are sold out, either by fans who have paid extra to see a premier game or by those extra fans who were willing to pay discounted prices to see a less-attractive matchup. Schools that tie both types of games into the same ticket package are missing the boat, he says, adding, "They can make more money by just properly pricing the games individually." Rascher's research into variable ticket pricing at the professional level found that proper pricing of individual games can increase ticket revenue by 20 percent or more, "which is pretty amazing," he says.

Simonson admits she hasn't yet completed enough research of her own to push ahead with variable ticket pricing. "I'm interested enough that we're going to explore it," she says. "But our football program is in such high demand that anything we do tends to have huge public relations potential, both positive and negative, so we tend to move a little slower on some things."

Conventional wisdom holds that a public that has long put up with fluctuating hotel and airline fares should easily accept variable pricing of sporting events. Rascher feels it's only a matter of time before variable ticket pricing becomes an invariable part of the collegiate and professional sports landscape. "I honestly think everyone will be doing this in the future," he says, "especially once the fans get used to the fact that the quality varies from game to game, and that they should be willing to pay more for a good game and less for a non-premium game."