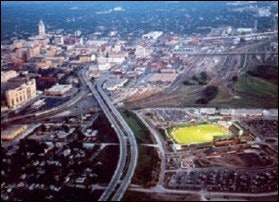

Due in part to what lies underfoot, these are heady times for Nebraska baseball. The 34-game 2002 home schedule during the Huskers' first season at Haymarket drew an average of 4,110 fans per game, ranking sixth nationally and marking the first time the program cracked the NCAA's top 10 in attendance. Each of Nebraska's three NCAA super-regional games played at the park last May outdrew the entire 1998 home schedule played at Buck Beltzer Field. Whereas baseball season ticket sales of 100 were once the norm, the athletic department this year and last sold out every one of Haymarket's 4,500 chair-back seats, which still leaves berm seating for another 4,000 fans.

Athletic administrators admit that the move to Haymarket Park last year coincided nicely with the team's on-field success, including College World Series appearances in 2001 and 2002. But there's no denying the facility's drawing power, and not just at the gate. "We really wanted to capture two things," Bob Burton, senior associate athletic director, says of the collaborative design process. "The Salt Dogs are in the entertainment business, and we had to attack it not only from that angle, but also in a way that would allow us to recruit student-athletes and make sure their competitive needs are met once they're here."

"There were things they wanted, and there were things we wanted," Salt Dogs President Charlie Meyer says. "The university brought a player perspective to the table in terms of amenities, while we brought more fan amenities."

Burton and Meyer agree that the product of their deliberations was well worth the effort, and their respective $10 million investments. Haymarket Park succeeds not only in brightening a main entry point to Lincoln (a goal of the project's third $10 million investor, the city itself), but in bringing operational synergy to state-of-the-art design. "Our season is starting up when their season is ending," says Meyer, whose team represents the first pro franchise to play in Lincoln since 1960. "We kind of feed off each other, and we're really utilizing the facility to its fullest potential."

Division I baseball powerhouses and community college teams alike have entered into facility partnerships with professional franchises in recent years, and still others view partnerships as having the potential to lift their programs out of backstop-and-bleacher obscurity. Many schools have found, however, that providing a professional atmosphere in which their team can play takes hard work.

Before Haymarket Park opened for business on June 1, 2001, for example, agreements had to be reached regarding ownership and lease terms, potential scheduling glitches, and the splitting of revenue and expense streams.

The city owns the park, with the remaining two parties receiving 35 years of use in return for their up-front investments. No lease money will exchange hands unless either user group chooses to exercise the seven five-year options built onto the back end of the deal.

To avoid the only possible scheduling conflict, the Salt Dogs prior to the start of each season request that the Northern League send them on the road during the weekend of NCAA regional play, in the event Nebraska again serves as host. The Salt Dogs also ask that they be scheduled to play in Lincoln during super-regional weekend, when the NCAA tournament field has sufficiently thinned, so as to ride the Cornhuskers' coattails should they advance that far. Last year, some 42,000 fans visited Haymarket Park between three super-regional day games and three Salt Dogs games played at night.

Maintenance of the facility is handled by employees of the Salt Dogs' ownership entity, Lincoln Pro Baseball, with costs shared between the Salt Dogs and the university (which pays extra for the work done on Haymarket's adjacent 2,500-seat softball complex). The parties share a common concessionaire and take a percentage of concessions sold at their respective games. University policy, however, prohibits the sale of beer at Huskers games. Both teams' games are packaged together for the sale of Haymarket's 16 suites and 24 rotational signage opportunities. The tri-action signs are programmed to conceal beer sponsorships during Nebraska games.

Despite the obvious synergy, Nebraska officials had to make sure that every aspect of the relationship complied with NCAA rules. "We had to make sure that when doing a partnership with a professional organization that we still had a line of demarcation there, that we weren't making revenue off a professional league," Burton says. "The important thing is that we were able to work out a joint-operating agreement prior to the building of the facility. It's worked out very well."

Other schools would like to put such synergy to work for them. Brigham Young University's Miller Park has for the past two seasons served as the temporary home of the Provo Angels, a Pioneer League affiliate of the Anaheim Angels. The rookie-league Angels were lured to Provo from Helena, Mont., with the promise that a city-owned park would be constructed for their use. BYU officials won't divulge financial details of the arrangement, calling it a favor to the city and a break-even proposition for the school. But they nonetheless see potential value in long-term partnerships. "We would be open to a more permanent arrangement, if the financial backing was there from the city or the team," says Matthew Nix, who handles game management for BYU athletics. "We don't really see the need for two nice stadiums in Provo."

Still, potential conflicts exist with BYU summer camps held at Miller Park. The two-year-old stadium, which houses the university's baseball and softball offices year-round, also lacks adequate administrative space for the Angels. "Logistically, it would make more sense for them to have their own stadium," Nix admits. "But we wouldn't mind having the money to help us maintain the stadium and deal with upgrades, as well as having the notoriety and publicity that comes from our stadium hosting professional games."

Seeking similar benefits, Penn State University is discussing the possibility of the nearby Altoona Curve's ownership group purchasing and moving a minor league team to the PSU campus, where varsity baseball facilities are "woefully inadequate," according to Pete Liske, the athletic department's director of special projects.

The university, which currently has a half-dozen parcels of land suitable for stadium development, would own the new facility, leasing it out to a summer-league team as a means to not only cover maintenance and upgrades, but turn State College into "a little bit more of a mecca for baseball," Liske says. "Obviously, it will be a nicer stadium if we can get a minor-league franchise in here. The nicer the stadium, the more attractive it is for our baseball squad."

Unlike Brigham Young, where interest in a permanent partnership with a minor league team is hamstrung by Miller Park's shortage of stadium office space, Penn State would be able to plan ahead for myriad facility requirements mandated by Minor League Baseball - from the sizes of dugouts to the intensity of field lighting to the number of showerheads. Moreover, a partnership involving Altoona's owners would skirt another of Minor League Baseball's maxims - that no franchise may enter the same county as another franchise or any of its adjacent counties without the established franchise's permission. Since the owners of each team in this case would be the same entity, that point is moot.

Facilities housing teams that operate in leagues independent of Minor League Baseball, such as Haymarket Park, need not adhere to such strict codes. But the independence of a professional partner doesn't eliminate every headache for the university involved.

In at least one coach's eyes, partnerships can lead to more frustration than they're worth. Understand first that Norm Schoenig, who has guided Montclair State University to two NCAA Division III championships, considers Yogi Berra Stadium, the $22 million on-campus facility MSU shares with the New Jersey Jackals of the independent Northeast League, to be the envy of either party's peers. There are times, though, when the coach would like to turn back the clock. "When you're practicing and playing on the field, obviously that's a good situation," Schoenig says. "But I would have preferred to stay at Pittser Field. I had more control. You need to have control over what you're doing."

Schoenig, who says he saw none of his design suggestions come to fruition, wishes he had more say in ongoing decisions relating to the scheduling of maintenance, as well as field and locker-room access. His practice times must be established well in advance, so as not to conflict with events coordinated by the stadium's sole benefactor, Floyd Hall Enterprises, which was granted long-term operational control of the facility upon donating it to the university in 1998.

The marriage of private business and collegiate baseball has been rocky, from Schoenig's perspective, due to a lack of operational consistency from day to day and season to season. "I have no idea if the things that were set up last year from day one are going to be the same protocol this year," he says. "It changes according to individual agendas. That's not the way you run an athletic program."

When structured carefully, though, partnerships can prove beneficial for all parties involved by putting the baseball teams of collegiate programs and professional franchises in facilities they otherwise couldn't afford. Given the recent baseball renaissance in Lincoln, Haymarket Park is a facility the Cornhuskers and Salt Dogs couldn't afford to be without.

"It enhanced our sponsorship, it enhanced our advertising, it enhanced our ticket sales, it enhanced our ability to host a regional and super regional," Burton says of Haymarket, which may one day help turn Nebraska baseball into a revenue-generating sport. For players taking the field this month, the park is already paying dividends.

"It's a miniature major-league ballpark," Meyer says. "For the collegiate players who won't get drafted to play professional baseball, they're playing in a professional ballpark right here during their college career."