Employee training and supervision are keys to reducing climbing wall injuries.

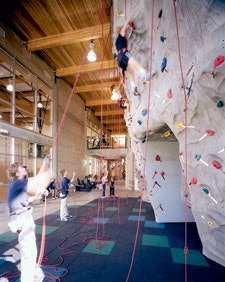

SHOWN THE ROPESProper staff training is one of the keys to helping keep climbers safe.

SHOWN THE ROPESProper staff training is one of the keys to helping keep climbers safe.A new study indicates that an estimated 40,282 individuals between the ages of 2 and 74 were treated in U.S. emergency rooms for climbing-related injuries between 1990 and 2007.

Researchers at the Center for Injury Research and Policy in the Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, examined data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System - a probability sample of hospitals nationwide maintained by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission and from which the total number of injuries treated in hospital emergency rooms can be extrapolated. They found that ankle and foot fractures, sprains and strains were among the most common types of climbing-related injuries, and the majority of them resulted from falls of 20 feet or more. Although this particular study did not include injuries that occurred to participants while mountain climbing or hiking, results did extend beyond the scope of fitness and recreation facilities to include walls at child-care centers, schools, amusement parks, campgrounds and other locations.

Climbing injuries are a given, says Bill Zimmerman, executive director of the Boulder, Colo.-based Climbing Wall Association, and they're most often the result of "pilot error" - an individual making a mistake. Significant differences exist between indoor and outdoor climbing environments and their levels of risk, but indoor facility owners still can "control what they can control," Zimmerman adds, through practical risk-management procedures such as employee orientation, instruction and assessment. "What's incumbent upon you, as an operator of a climbing wall, is to make sure that your staff is trained and experienced in climbing techniques and procedures - and that your employees stay up to date with those techniques and procedures," he says. "Somebody will spend $1 million on a climbing wall and won't spend $10,000 or $20,000 on training and development for their staff. That's my frustration with this whole business."

All major full-service climbing wall manufacturers provide training for facility employees, as do most local climbing gyms, Zimmerman says. If budgets are tight, managers should consider sending only one employee to a training session, and that individual then can educate other staff members.

As climbing continues its ascent among recreation activities - nearly five million people climbed indoors in 2008, according to the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association - staff and user education will take on even greater importance. "Initially, rock climbing was a sport for risk takers and adrenaline junkies, and now it's much more mainstream," says Lara McKenzie, senior author of the injury study, which was published in the September online issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. "So the demographics have shifted, and recreational climbers may be younger and more inexperienced."

Zimmerman suggests that greater oversight of a climbing structure is especially necessary in facilities such as health clubs, YMCAs, and college and municipal recreation centers - places in which climbing is "incidental" to other operations. "Who knows what kind of resources are allocated to that big climbing wall in the lobby?" he asks. "Who knows if there is a full-time staff member responsible for it?"

While not de-emphasizing the importance of the latest injury study, Zimmerman remains skeptical of research that paints climbing with a broad brush. "The fact of the matter is that climbing is pretty innocuous, and generalizations made about climbing are going to be somewhat specious," he says.

"This kind of study is a good surveillance tool," McKenzie maintains. "It lets us know what types of injuries are occurring, who is being hurt and what they were doing when they got hurt. And it gives us a nice jumping off point to open up the discussion. Now that we've identified the types of injuries, we might be able to look more closely at what we can do to prevent them."