As the 1995 NCAA champion in the 400 meters and an aspiring Olympian, Nicole Green could have used some advice when it came to selecting the best representation to help a professional track and field career hit full stride.

As the 1995 NCAA champion in the 400 meters and an aspiring Olympian, Nicole Green could have used some advice when it came to selecting the best representation to help a professional track and field career hit full stride. But none was available to the Kansas State University student-athlete at the time.

Now, as director of compliance at the University of Memphis, Green seized the opportunity last year to spare student-athletes on her watch from similar confusion as they contemplate turning pro, with - in all likelihood - the assistance of a sports agent. Memphis thus became the first school to employ the services of Hollywood, Fla.-based Collegiate Sports Advisors, which staged separate compliance workshops and an agent day on campus. "I didn't have all the information and knowledge that I needed as a student-athlete to make an informed decision, and that's basically one of the reasons that we set up the program here at the university, because we do have individuals who are making it to the next level," Green says. "I didn't want them to go through what I did. When I graduated, I did receive offers, but if I would have had more information on the front end, I would have been better prepared for it."

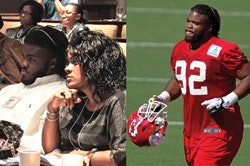

Among the 13 student-athletes (not to mention dozens of parents) who attended the Dec. 3 agent day were Dontari Poe, a junior defensive lineman selected 11th overall in the 2012 NFL draft by the Kansas City Chiefs; Will Barton, a sophomore guard and the 40th pick (by the Portland Trail Blazers) in this year's NBA draft; and Adonis Thomas, who decided instead to return to the Tigers' men's basketball team for his sophomore season. They were introduced to more than 20 agents - each thoroughly vetted by CSA co-founders Darren Heitner, a one-time agent himself and editor of sportsagentblog.com, and Jason Belzer, a Rutgers University sports management professor who also provides legal representation to roughly two-dozen collegiate coaches. The attending agents chose with whom they wished to meet, and the individual student-athletes retained final veto power over all meeting proposals.

It's an organic process. "We don't recommend an agent, but we'll provide information about each agent beforehand so the student-athletes know the kind of person he is and the players that he already represents," Belzer says. "With Poe, we explained to him, 'This guy represents three defensive linemen in this year's draft. You need to take that into consideration, because there could be a conflict of interest in terms of how he's going to be able to present you to different teams.' It takes up quite a bit of time, but that's the resource that we're giving the school.

"We set up the interviews, educated the student-athletes, vetted the agents - basically everything from A to Z so that the athletics department itself really didn't have to worry about a thing. As a company, we're trying to facilitate these processes for the schools that may not have the resources to hire someone full-time to do it or just don't want to deal with the subject in general."

Several schools have been more reactive than proactive when dealing with the subject of sports agents in recent years. Even with federal legislation such as the Uniform Athlete Agent Act (2000) and the Sports Agent Responsibility and Trust Act (2004) on the books and gaining widespread acceptance at the state level, not to mention evolving guidelines provided by the NCAA that define agents and permissible contact, schools that have experienced recent trouble on the agent front have taken it upon themselves to craft their own regulations. And that's not a good idea, if you ask Heitner.

In a year in which the NFL Players Association has eliminated its so-called "junior rule" - thus freeing agents to contact any undergraduate student-athlete - certain schools are barring their doors. "What the University of Miami is trying to do is effectively prohibit all forms of communication while the players are considered student-athletes. So whether they're freshmen, sophomores, juniors, seniors - no interaction in person, over the phone, via e-mail," Heitner says. "Then you have the University of North Carolina and the University of Washington - and they're not the only schools - which have introduced rules specifying days that agents can have in-person contact, certain times that they can e-mail student-athletes and call them but not see them in person, and then times when athletes are completely off limits."

Such campus-specific regulations, which Heitner considers political maneuvers more than anything, are highly ineffective and even counter-productive, he says. "Take Miami, where they're trying to regulate all forms of communication between the players and the agents. Who does that serve to benefit? Well, it doesn't serve to benefit the player, because it effectively inhibits the player from getting any good information. So, if the player follows the rule, that player will go through three or four years at the school and then be thrown into this sea of swarming agents and not really have enough time to effectively vet them and figure out which one is the best fit. In my mind, there should be no specific regulation that limits communication between agents and players. I really think the schools are getting it all wrong by trying to curb that process of getting information. If anything, they should be encouraging players to communicate with agents so that they make an informed decision and not just one that's based on who has the deepest pockets." (It was Heitner's coverage of these issues as presented in Oliver v. National Collegiate Athletics Association that garnered his blog's first true surge in readership and respect.)

Not surprisingly, Belzer agrees. "It's absolutely ridiculous stuff that makes you say, 'Do you think the agents really give a s--- what the school's policy is regarding this?' If they're going to want to talk to players, they're going to go out and do it," he says, a mere five years removed from serving as a campus runner for an NFL agent. "I was asked to go out and recruit players. That meant hanging out with them, taking them out, having a good time. Do you think I cared what the school said about what I was doing? It didn't even know I existed."

"Meanwhile, if there is any violation, what can the school do to the agent?" asks Heitner, before providing the answer. "Absolutely nothing." Because schools have no real jurisdiction over the agents themselves, other than banning them from campus, such regulations serve only to punish those agents who follow the rules, Heitner adds.

Just how big are the swarming seas? Belzer estimates the number of agents working in NBA circles at more than 300, while approximately four times as many NFL agents currently exist, and he further estimates that up to half the agents operating in a given state are not registered in that state. If caught, unregistered agents can be fined, jailed and/or lose their license under the UAAA. Additional UAAA provisions include prohibiting agents from giving false or misleading information, giving student-athletes the right to cancel an agent contract within 14 days, and stipulating that an agent contract must contain notification that signing the contract will make the student-athlete ineligible for college competition. It also gives schools the right to seek damages caused by violations of the act, according to NCAA spokesperson Stacey Osburn.

The law has "pretty significant teeth," according to Christian Spears, senior associate athletics director for administration at Northern Illinois University and the current president of the National Association for Athletics Compliance. Yet, despite Illinois being one of the 40-plus states that have adopted the UAAA (with football hotbeds Alabama, Florida and Texas among the leaders in enforcement, according to Heitner), NIU conducts due diligence in the form of its own agent registration program. "We require the agent who wants to solicit or provide information to our student-athletes to register with us," Spears says. "Then we confirm that they are, in fact, a legitimate member of whatever the professional association is - usually the NFLPA - and that they're certified in good standing. And then we provide that information to the student-athlete who they're looking to recruit."

Moreover, the NIU compliance department prescreens the agents' incoming correspondence. Says Spears, "They have to send us the information that they want to provide to the student-athletes prior to sending it to the student-athletes. The student-athletes don't have a direct mailbox with agents. It comes into the compliance office as part of the agent registration program and is disseminated back out to the student-athletes."

For its part, the NCAA offers online content, videos, an athletics agent information packet and a list of questions student-athletes should ask agents. It also makes annual rules presentations to agents - "new and seasoned alike," says Osburn - through professional players' associations.

"They've done well in stepping up their game," Belzer says of NCAA staff. "The problem is that the NCAA works at the pleasure of the universities, and until the universities themselves step up, it's going to be very difficult for them to be able to stamp out these issues."

Osburn points out that NCAA members are taking matters into their own hands in ways beyond annual agent days - be they in-house, as many schools choose, or outsourced. "Some institutions check comp ticket lists to ensure that no agents are included," she says. "Others close all practice sessions so agents cannot gain easy access to student-athletes. Others film and monitor the game tunnel to make sure that agents aren't in that proximity."

To bring agents onto campus in what Belzer calls the "controlled, friendly environment" provided by CSA, schools can expect to spend between $10,000 and $15,000 per year (two campus visits, including a compliance workshop and an agent day), substantially less, Belzer is quick to reveal, than the entry fee to a college basketball tournament he runs. But the beneficiaries extend beyond campus. "Because of the agent day that we held at Memphis, the state of Tennessee was able to increase its agent registration by more than 10 percent," Belzer says. "I believe it was more than $10,000 worth of revenue to the state off of this one day."

The Memphis contract with CSA extends through this year, but other schools have been slow to outsource their agent education. One reason is that coaches bent on total control of their programs may be wary of their student-athletes potentially being advised to leave school early. That wasn't the case at Memphis, according to Green. "We are an educational institution, so we're providing our student-athletes, as well as our coaches, with educational information that's going to help them," she says. "I think our coaches here have made the decision to do what is in the best interest of the student-athlete."

"If you're going to recruit student-athletes to come to your university, the least you can do is make sure that they're taken care of when they're leaving to become professionals. But a lot of programs just don't have that opportunity or ability to do it," Belzer says. "Every university has a career services department that it spends money on to make sure that its students are able to find jobs when they graduate. But very few universities have a career services office for student-athletes who may be going pro. That's really what we're doing in this process."