The University of Vermont Recovers From a Scandalous Hazing Incident

Between icons labeled "Today's News" and "Today's Calendar" on the University of Vermont's news-and-events Web page is a link to articles chronicling a saga that began last fall but remains fresh in the minds of UVM officials, students and staff. It reads: "News Related to Hockey Hazing."

The collection of more than a dozen press releases dating back to Dec. 3 covers ongoing developments related to allegations by a freshman walk-on goaltender that he and other newcomers to the Catamount hockey program were subjected to abusive behavior at an Oct. 2 party hosted by the team's captains. Details of the incident, which involved player nudity and underage drinking, have been well-documented by the mainstream media. Amid the fallout: The suspension of the entire team after it was determined players had not been completely truthful with investigators. The final 15 games of the season were canceled.

To some, including many of the hockey players, the game cancellations represented an all-too-quick fix for a problem that was blown out of proportion - or at least wasn't isolated to one team. Players said they felt the university had made examples of them. However, for the UVM community as a whole, lopping off nearly half a season's worth of games involving the school's most popular athletic program became the amputation necessary to begin a long and difficult healing process.

"For me to even talk about it is painful," says Athletic Director Rick Farnham, a former UVM football player who has been part of the school's athletic administration for 25 years. "We had a great program all winter - with the ski team, the basketball teams, the track teams. They had great winters. But every time you read something in the press, they've got to go back and point to the fact that the hockey hazing happened. It continues to open the wound."

The hazing situation cut deepest in early December, when Corey LaTulippe, the freshman goalie who by then had left the university, filed a federal lawsuit against coach Mike Gilligan, UVM President Judith Ramaley and the team's three captains. With a potentially lengthy legal ordeal pending, school officials faced two immediate challenges: to correct a serious problem within one (or perhaps more) of the university's intercollegiate athletic programs and to manage the barrage of public scrutiny their past and future actions would draw.

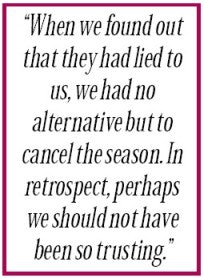

According to Ramaley, who announced the season termination Jan. 14, the game cancellations resulted as much from a betrayal of school officials' trust in student-athletes as it did from acts of hazing. In fact, Ramaley says that the season likely would have remained intact had players been forthright about their Oct. 2 actions. "We assumed that our students were being honest with us during the investigation," she says. "Our subsequent steps were based on that assumption. When told to appear for interviews, the players were warned by the coach that their failure to tell the truth would result in their removal from the team. When we found out that they had lied to us, we had no alternative but to cancel the season. In retrospect, perhaps we should not have been so trusting."

"It says something about the culture of these kinds of things, when a team gets together and acts collectively," says Farnham about the conspiratorial nature of the players' testimony. "It's not the individual who knows better. Sometimes the collective wisdom of a group like that is not half as wise as the single individual."

Vermont Attorney General William Sorrell, after completing a seven-week investigation at the university's invitation, blasted UVM administrators for failing to react to warnings voiced by LaTulippe in September that hazing was taking place within the hockey program.

On Feb. 3, the day Sorrell's findings were released, Ramaley publicly admitted that the university's response had fallen short. She took full responsibility and vowed to learn from mistakes made.

Three weeks later, Ramaley released the "Report of the President's Committee on the Prevention of Hazing in Intercollegiate Sports at the University of Vermont," a 17-page document detailing 53 recommendations, approximately half of which deal with how to better respond to allegations and incidents of hazing. (The complete report is available at http:// universitycommunica tions.uvm.edu/.Page= committee.html.)

Next, Ramaley formed an implementation team headed by UVM's vice provost for undergraduate education and the school's associate vice president of student affairs. "They are responsible for ensuring that a comprehensive package of strategies is in place by this fall," Ramaley says.

For his part, Farnham chose not to wait for the committee's report. ("There were five things that I thought we needed to do immediately," he says.) Farnham's initiatives, which in many ways mirror the spirit and goals of the committee's recommendations, are also slated for implementation by the start of the new academic year. They include:

- development of a contract of understanding that defines hazing, to be signed by each student-athlete;

- creation of preseason community service projects for each UVM athletic team to foster bonding between new team members and veteran athletes;

- institution of a leadership program for team captains that addresses their roles and responsibilities, including taking a stance against hazing;

- establishment of an ongoing educational program that gives each team the opportunity to hear guest speakers and to participate in discussion sessions between team members and school administrators;

- encouragement of each team's members to become goodwill ambassadors for UVM and its athletic department, emphasizing the positives each has to offer.

Farnham says he has sent copies of these initiatives, along with copies of the report by the president's committee and a PowerPoint presentation to facilitate group discussions, to 20 colleagues requesting help with hazing issues on their respective campuses. "It's something, in talking with our counterparts at other institutions, that we've realized is a cultural thing," Farnham says. "It's prevalent everywhere, not just at the University of Vermont. We're trying to learn from it and do the right thing."

The athletic director has also worked toward compensating institutions scheduled to host the Catamounts during the final months of the hockey season. He intends to compensate Dartmouth, Vermont's travel partner, for extra lodging and meal expenses incurred during four road trips the Big Green was forced to take alone. He has offered UVM season-ticket holders the choice of a cash refund or credit off the price of 2000-2001 tickets, and he expects a near 100 percent renewal rate.

"You can do everything you can to try to find dollars," says Farnham, who estimates the cancellation of games cost the athletic department nearly $300,000. "But what's difficult now is to get these students to learn from what happened, to change our culture in all programs and to work with other schools to try to combat this kind of thing."

Farnham anticipates no ill effects for the school's recruiting efforts. In fact, he feels parents might find solace in the knowledge that UVM, perhaps more than other schools, has identified hazing as a problem and is dealing with it. "We do take it seriously," Farnham says.

As if setting an example with regard to the latter of his five initiatives, Farnham pitched a story on the Vermont ski team to a USA Today writer while attending the NCAA soccer championships in December. The article ran as the main feature in the paper's Jan. 26 sports section. But even this story celebrating a successful and atypical intercollegiate sports program was put in a context opposite the hockey scandal, which received mention in the article's second paragraph. And only nine days later, USA Today ran another sports cover story on UVM, this time focusing solely on the hazing scandal and its potential repercussions in the wake of the attorney general's report.

Hundreds of similar newspaper clippings fill a folder in the UVM communications office, the result of intense media interest in the scandal from late December through March. "For three or four months, it dominated the work that was done in our office," says Enrique Corredera, UVM's director of communications. "It quickly became one of our thicker files."

Newspapers from Toronto to San Antonio ran opinion pieces on the cancellation of the hockey season, and wire-service reports on LaTulippe's lawsuit appeared in papers as distant as The London Free Press. It was Corredera's office that packaged the university's press releases under one conspicuous Web icon, mostly as a convenient and direct pipeline of information from the university to its constituents, but also to complement outside media coverage.

"We tried our best to present all aspects of the situation - of course, not in the same way the media would go about it. That's not our purpose here," Corredera says. "But we wanted people to at least have a place where they could get more details about aspects of the situation we were dealing with that, in our judgment, were not being fully explored in the media." UVM faced a "very difficult dilemma," he adds, when it came to protecting students' legal right to privacy while also responding to what quickly became "very loud needs of the media to get at all the information from the start."

Though the wave of media attention has ebbed during the summer months, Corredera expects interest to surge again when school reconvenes this fall, and certainly later, when the hockey team returns to the ice. The Web site will be updated as reforms are implemented, he says, adding, "I'm not sure the regional and national media outlets that were interested in the cancellation of the season will be equally interested in what it will be like for Vermont to start a new season."

Regardless, the university is prepared to add new, more positive chapters to the saga. "I think our campus in some ways is looking forward to that opportunity," Corredera says. "This has been a painful year, but there's a lot of very thoughtful work that's been going on and will continue to go on to try to make things better."

Says Ramaley, "Although we cannot hope for a quick fix for a problem as deep-seated and complex as this one, we can make a real difference in the lives of our students. And we can offer guidance to our colleagues at other institutions who are ready to face up to the seriousness of this problem. We are a stronger university today because of what we have been through."