Peer Pressure Drives Drug Testing at One South Carolina School

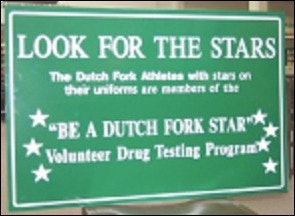

It's hard to miss the large signs posted at all Dutch Fork High School athletic events, the ones explaining that student-athletes with a star on their uniforms are members in good standing with the school's voluntary drug-testing program. Administrators at the Ballentine, S.C., school hope the signs' prominent placement and straightforward message to parents, peers and the public will convince players to join the "Be A Star" program, which kicked off with the 2001 spring sports season.

Once student-athletes commit, they're subjected to a $10 on-the-spot urine test, as well as subsequent unannounced tests, also $10 each. Players - most of them from white-collar, middle and upper-class families - are responsible for footing the bill, except in extreme financial-need cases. Once players enroll in the program and test negative for drugs, they earn a uniform star and (most likely) the respect of their school and community peers.

Bill Kimrey, Dutch Fork's athletic director and varsity football coach - and the man who developed the "Be A Star" program - acknowledges the widespread off-campus use of marijuana and other drugs by his 600-plus student-athletes. But he reports that about 80 percent of Dutch Fork's 200-plus spring sports players submitted to initial tests, an encouraging sign that this approach to just saying no may indeed work.

The coaches of participating players are not informed of the test results, and anyone testing positive must attend a meeting with his or her parents or guardians, the school's counselor and Kimrey (or another school administrator if the player is on the football team). A second offense calls for a meeting with an outside counselor, and a third offense results in the player's suspension from athletics for the rest of the year - "which at that time is probably the least of a parent's concerns," Kimrey says.

"We don't know who's doing drugs. But we at least know who's not doing drugs, because they have stars on their uniforms."

"I love that approach," says Tim Flannery, an assistant director of the National Federation of State High School Associations."I like the idea of using peer pressure, because if you don't get tested, you're essentially saying, 'I'm not clean.'"

Some observers have labeled the policy as a "reverse scarlet letter" approach, a depiction that makes Kimrey bristle. "Anytime an athlete does something wrong, he's singled out," he says. "What's wrong with singling out some kid for doing something right? Some students have said it's not the mission of the school to invade their private lives. But if kids are endangering their bodies, I think it is our mission to get involved."

Apparently, so do administrators at other schools. While mandatory random drug testing is nothing new in school districts across the country - the 1995 Supreme Court ruling in Vernonia School District 47J v. Wayne Acton permitted schools to test student-athletes for drugs - voluntary testing is a relatively recent development. Last fall, Frederick Douglass Senior High School in New Orleans became the first public school in Louisiana to offer a voluntary drug-testing program. Using hair analysis - a procedure in which sample strands are tested for marijuana, cocaine, LSD and speed every three months - school officials test all willing students, not just athletes. More than 50 kids signed up for the pilot program by noon on its first day, according to the Times-Picayune of New Orleans,

Also last fall, Northwest Suburban High School District 214 in Chicago approved a policy allowing all students to be tested for drugs via urinalysis on a voluntary basis - even though not all of the district's schools committed to the program. The move came on the heels of (but reportedly was not related to) the suspected heroin-related deaths of two teenage boys who would have been seniors at District 214 schools.

Because these drug-testing policies are voluntary, the American Civil Liberties Union has stayed away from challenging them, despite the group's well-known opposition to any kind of drug testing.

Mandatory drug-testing policies are another matter, for example: the Supreme Court of Indiana was expected to endure the ACLU's strong opposition to mandatory testing last month, as justices were scheduled to hear oral arguments in a case brought by the ACLU and the parent of a child enrolled in the Northwestern School Corporation of Howard County. The state's Court of Appeals ruled last August that the district's mandatory drug-testing policy - which encompassed all students who participate in athletics and extracurricular activities, as well as those who drive to school and park on campus property - was unconstitutional because it denied students their Fourth Amendment right, namely the right to reasonable suspicion before being searched. "That decision was so broad that it could affect university drug-testing programs, too," says David Emmert, general counsel for the Indiana School Boards Association, which has gotten heavily involved in the case. (Perhaps that's why such venerable state universities as Purdue, Indiana and Ball State filed amicus briefs in support of the Northwestern School Corporation.)

Meanwhile, the case has had a chilling effect on the more than 70 districts (in Indiana, they're called "corporations") that mandate random drug testing in Indiana. All but one of those districts, Emmert says, suspended their drug-testing policies when the appeals court handed down its decision. But since the state's highest court agreed to hear the case and rendered the appellate court's decision null and void, at least 15 districts have resumed testing. "I have had athletic directors tell me that students have been drinking and taking drugs again because they aren't being tested," Emmert says.

"Anytime you go beyond testing athletes, there's a new case," says Ken Shultz, athletic director at Homewood-Flossmoor High School in the Chicago suburb of Flossmoor. Back in 1990, his high school was among the first in the country to implement mandatory drug testing for student-athletes. The school spends about $25,000 a year - drawn from an estimated $40,000 in annual gate receipts - testing its 1,400 student-athletes for 10 drugs, plus alcohol, Shultz says.

Homewood-Flossmoor's policy - which suspends violators from athletics for two, four or 52 weeks, depending on the number of offenses - was implemented based on results from three school board meetings and student surveys, and consultation with area hospitals about their pre-employment drug-testing programs. The overwhelming response to the surveys favored some sort of testing procedure, Shultz says. And so far at least, there have been no legal challenges.

"Athletics is a privilege," he says, echoing the Supreme Court's 1995 opinion in Vernonia, which stated that students have a reduced expectation of privacy and should expect intrusions on their normal rights and privileges when they choose to participate in school athletics. "It's voluntary to go out for athletics, and there's a certain set of rules athletes have to follow that differs from those of the general student population."

Do those rules also apply to a calculus whiz in the math club, the lead actor in a school play or any student who drives his or her own car to school? The outcome of the Indiana Supreme Court case could have implications on the kinds of drug-testing procedures districts in Indiana and other states follow. For example, Dutch Fork administrators would like to use Kimrey's peer-pressure approach to drug-testing on many more students - from those in the band to the 145 or so involved in the school's Junior Air Force ROTC program.

Should voluntary drug-testing programs carry on unchallenged in the nation's high schools, time will tell whether they can succeed both at suburban, well-heeled schools like Dutch Fork - where all team practices are open to parents and family members - and in more urban school environments. "I've worked at some schools where I didn't see the parents for four years," Kimrey says.

Indeed, the biggest challenge Kimrey claims his staff currently faces is finding the best way to affix those stars to players' green, white and silver uniforms. The stars used during the spring soccer season were too small to be seen from across the field, and larger iron-on stars could cause other elements of the uniform to melt if not affixed properly. But while some kinks still need to be ironed out, the "Be A Star" program has already made an impact on the Ballentine community. A local Coca-Cola bottler has pitched in $1,000 to pay for the stars, signs and other associated costs, and gift certificates, movie coupons and other prizes donated by area businesses are raffled off each test day.

"The idea is not to eliminate kids from athletics," Kimrey concludes. "It's to help kids. Even the kids who don't sign up are being helped, because they had to sit down and talk about drug use with their parents. I think there were a lot of interesting conversations going on around supper tables about this."