A Public-Private Collaboration Rescues Football at Two Milwaukee High Schools

The 500 students gathered in Messmer High School's gymnasium "went nuts," says athletic director Joy Bretsch, when she announced this spring that the Milwaukee Catholic school would field a football team this fall for the first time in nearly two decades. And even though that team is part of a two-year cooperative program with 700-student Shorewood High School (located minutes away), a newfound sense of school pride carried Messmer's students and staff through the remainder of the school year.

Recalling the day last September when Cindy Wilburth, Shorewood's athletic director, pitched her on the idea, Bretsch says: "When I got the call, I ran upstairs to Jeff [Monday, Messmer's principal] and told him he had to sit down. The kids had been begging us and begging us to get a football team, and we kept saying, 'We're looking into it.' When Cindy called, it's like our prayers had been answered."

Divine intervention or not, the Shorewood-Messmer football partnership appears to be the boost both schools' athletic programs desperately needed. Last season, Shorewood fielded 13 varsity football players - including 11 seniors and two sophomores. The sophomores also played on the freshman team, which only had nine other players. With most of the varsity lineup now gone to graduation, the fate of Shorewood's football program, which went 0-63 during a recent seven-year period and has won just once in its last 33 games, would have been in dire jeopardy without Messmer's cooperation.

Messmer, meanwhile, has no outdoor athletic facilities and only three fall sports - girls' volleyball and boys' and girls' cross country - and had been losing students to Milwaukee-area public schools in part because it hadn't fielded a football team since the early 1980s. (Although it's now one of southeastern Wisconsin's fastest-growing high schools, Messmer's troubles once extended well beyond the gridiron; in 1984, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee ordered the school closed because of declining enrollment and increasing costs. A determined group of Messmer supporters, however, wouldn't let that happen, and the building remained open as an independent Catholic high school.)

Messmer will pay Shorewood $300 for each Messmer player, which should be enough to cover the cost of extra uniforms and help defray Shorewood's maintenance of 2,000-seat Erickson Field. Because neither school's budget allows for new uniforms, Shorewood-Messmer players will wear the Greyhounds' red and gray colors with helmets sporting a new blue "M" to signify Messmer's participation and represent its school colors. Messmer also will provide two part-time coaches who will join Shorewood's freshman and varsity coaching staff of five. Wilburth plans to hold interschool meetings for players' parents in order to promote further goodwill, and she insists all players from both schools learn, memorize and sing each other's school songs before games.

How successful the new Shorewood-Messmer Greyhounds football team will be is anybody's guess. "If you ask my coach, he'll say 9-0," Wilburth laughs. "Realistically, we hope to win a couple of games, and we're just looking to be competitive the whole game."

The low expectations reflect two challenges facing coaches and players - the attitude adjustment required of Shorewood players and the physical endurance required of Messmer players. "Our kids are a bit skeptical right now," Wilburth says. "They're concerned their position might be taken. In the past, if a kid didn't show up for practice, he probably would still play, because otherwise we would have had to forfeit."

Down the road at Messmer, students were feeling more soreness than skepticism after participating in April conditioning workouts with Shorewood players. "You can't put players on the field who don't know what they're doing," Bretsch says. "And some of our kids didn't realize what the commitment level was. I think they just thought they'd go on the field and start playing." Already, expected participation by Messmer students has fallen from more than 60 to between 30 and 40.

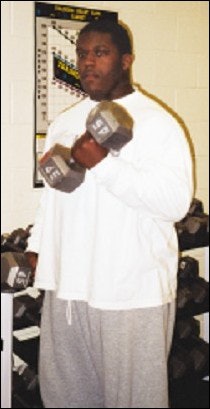

One Messmer student who is up for the challenge is Nate Shorter, now a junior. Although his mother wanted him to attend Messmer, Shorter was among the frustrated students who might have transferred schools had Messmer not formed its football alliance. "He's been lifting weights every day," Bretsch says. "He's bulked up to 260, 270, and he's huge. Just huge. I think you'll see him in the pros. I would put money on it." Shorter has committed to staying at Messmer, and the school in turn has named him team captain.

Shorewood-Messmer's football partnership could foster other cooperative opportunities between the two schools, including the marching band, cheer squad and drama department. (Shorewood already has gymnastics and hockey co-ops with two other public schools.) Another benefit of the collaboration is that Messmer students now will be able to participate in proper homecoming festivities, which previously revolved around a basketball game that lacked much of the pomp and circumstance of a traditional homecoming football game.

The new football team is being formed just as Messmer has begun breaking in its new gymnasium, complete with updated locker- and weight-room facilities. As a result, athletics and fitness have suddenly assumed more prestigious positions at Messmer. "Academics still come first," Bretsch says. "I've told the students that their grades have to be solid. If this co-op program has done anything, it's pushed kids harder than ever, because they have to maintain the grades to play."

The Shorewood-Messmer partnership is bound to be one of Wisconsin's highest-profile high school co-op programs this fall - and not only because it's in football, rather than in more common co-op sports like swimming, diving, gymnastics and hockey. It's also among the first public-private co-ops to form since the Wisconsin Independent Schools Athletic Association disbanded last year, leading Messmer and many other private schools to join the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association for the 2000-01 sports seasons. For decades, the WIAA had been one of only a handful of interscholastic athletic associations nationwide to forbid the membership of private schools.

Messmer's evolution from having no football team to fielding a co-op team took about six months. It could easily have taken much longer, but Monday, Messmer's principal, reports that there was little dissent among the school's board of directors. Their main concern wasn't Messmer's private-school tradition, but rather its academic integrity. "There are high expectations for our student-athletes," Monday says, adding that Shorewood administrators adhere to the same philosophy of academics over athletics. "I wasn't surprised by our board's overwhelmingly positive reaction. It just seemed like a natural fit to me."

Both Bretsch and Wilburth also downplay comments that their collaboration could become a model for public-private co-ops. "The goal was to do whatever it takes to save Shorewood football," Wilburth says. "Our priority right now is making sure the football program is successful."