Money Trickles Down From the Pros to Denver Middle Schools

In Colorado, a state whose residents were the first to embrace advertising signage on the outside of school buses nearly a decade ago, corporate sponsorship of just about anything has become a way of life. Perhaps that's why Jon Wolfer, middle school athletic manager for Denver Public Schools, can claim he hasn't heard a single complaint about the commercialization of an interscholastic athletics program for the city's sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders called - are you ready for this? - the Denver Nuggets/ Colorado Avalanche Prep League.

Begun in 1997 as a way to resurrect a program dormant since the mid-1960s, the two-division Prep League serves 21 schools and more than 2,650 student-athletes (almost 20 percent of the student population). The program's costs - uniforms, equipment, coaches' salaries and other expenses - are covered entirely by the $270,000 or so a year provided by the NBA's perennially mediocre Nuggets and the 2001 NHL Stanley Cup champion Avalanche (both owned by Stan Kroenke), as well as a local office-supply company, a health-care provider, and grants from the Robert R. McCormick Tribune Foundation.

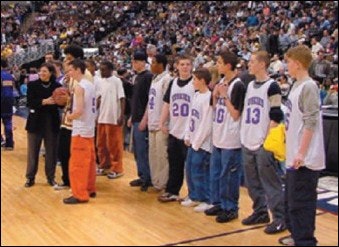

In return, the Nuggets and Avalanche become virtually every young local student-athlete's favorite team. The professional players participate in basketball and floor hockey clinics at the schools, boys' and girls' basketball championship games are played at the Pepsi Center (the teams' home arena), and the Nuggets even provide vouchers to their games for schools' teams and their coaches.

"They just can't let go of turning this into a marketing opportunity, can they?" asks Alex Molnar, director of the Commercialism in Education Research Unit of the Educational Policy Studies Laboratory at Arizona State University. "The program would be so much more laudatory if they would."

But the Prep League's sponsors aren't simply relying on name recognition. While they do cede control and operation of nine sports - including flag football, volleyball, cross country, boys' and girls' basketball, baseball, soccer and floor hockey - to the district and each of the schools' athletic directors, sponsors are directly involved with administrators in making sure student-athletes maintain high academic eligibility standards. To participate in middle-school sports, players must maintain a weekly C average or better in each class. Otherwise, they sit on the bench for the week. Once they hit high school, the ineligibility period increases to a semester, although the academic standards are lower.

The goal, officials say, is to encourage students to improve academic achievement and stay in school. One upshot of this arrangement is that the Prep League feeds Denver's high schools with a "bumper crop" of freshman athletes, Wolfer says. "The intent was not to build up our high school athletic teams," Wolfer contends. "That's just one of the positive benefits of the program."

Now, four years later, the positive (and negative) effects of the program are starting to be felt at some, if not all 10, of Denver's public high schools.

First, the positive. In addition to building their confidence levels, many middle-school student-athletes have begun learning the value of teamwork, sportsmanship and self-discipline at a younger age - thanks to the Prep League, says Nancy Werkmeister, athletic coordinator and girls' basketball coach at Martin Luther King Jr. Efficacy Academy, which at 1,515 students boasts the largest enrollment of any Denver public middle school. "This isn't a program where if you sign up, you get to play," she says. "You have to develop a practice ethic and you have to develop teammate relationships."

"Sports is hard work," adds one Denver high school athletic director. "It means getting up early, eating right and keeping your grades up. Kids are now making the connection between sports and these other areas earlier in life."

Take South High School, whose enrollment includes students from 40 countries who speak 30 different languages. Vice principal and athletic director Skip Wiggs credits the Prep League with introducing sports to immigrant and refugee students from countries where organized athletics hardly exist. By the time those kids enter high school, many of them are ready to compete in games they otherwise might not have fully understood.

At Martin Luther King Jr., coaches do not cut players in most sports (boys' and girls' basketball are the exceptions), and Werkmeister doesn't hesitate to encourage her school's coaches to bench their top players. "I make some of the kids sit on the bench and understand the concept of not being in the game, supporting their teammates and letting somebody else be the star for awhile," she says.

That approach appears to be working. Last year, all five starting players on Martin Luther King Jr.'s eighth-grade girls' basketball team chose to attend the same high school this year - a rare occurrence in Denver, Werkmeister says, where many student-athletes take advantage of the district's open-enrollment policy. "Those girls made that decision on their own," she says. "We just try to instill in these kids the idea that if they work together, play together and stay together, they will be more successful during their high school years." Some Prep League players, given their experience in middle school, might even make the junior-varsity squads of their respective teams as freshmen.

That's all well and good, says Molnar, who nevertheless questions the fairness of the Prep League, Colorado's only district-regulated middle school interscholastic athletic program. "Are athletic programs integral to academics?" he asks. "If the answer is yes, then deals like this are harmful because they obviously create enormous inequities for schools that don't have these programs. If the citizens of Denver want this program, they should pay for it. If they can't pay for it, then don't have the program."

And it's not just the inequities between Denver's middle schools and their counterparts in the rest of the state that concern Molnar. While the city's middle school student-athletes benefit from major corporate sponsors, Denver's high schools don't. As a result, they face a burgeoning number of players, overcrowded facilities and tighter athletic department budgets. "Let's say my student-athlete population goes up 10 percent this year," says Wiggs, whose school has 23 sports teams and does not cut freshmen. "Do I have 10 percent more uniforms. Do I have 10 percent more coaches. Do I have more flexibility in my facility scheduling? No. My overall athletic budget is less this year than it was last year. I probably need another $500 for each of my sports teams, plus a lot more than that for football."

Given the Prep League's success - defined both by its popularity and its drive for academic excellence - might this precipitate a more commercialized future for interscholastic athletics, particularly at the lower grade levels. "This is not something that should be done without raising important questions regarding its impact," Molnar warns. "The harmful and exploitative elements of the program ought to be discussed. Do we want to turn our schools and schoolchildren into walking billboards for corporations?"

Wolfer sees the future a bit differently. "Perhaps at the middle-school level, that's where things are headed," he says. "But I don't think there are any high schools in danger of losing public funding."