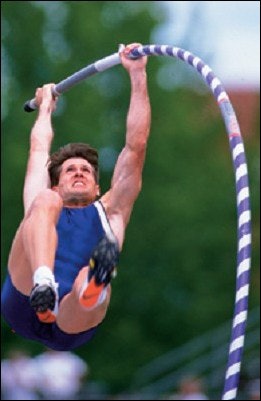

A series of pole vault deaths boosts administrators' obligations to young athletes

This past April, Samoa Fili, a 17year-old high school senior from Wichita, Kan., died after he struck his head on concrete extending from beneath the landing pad during a high school pole vaulting competition. While the death of a single athlete is tragic enough, Fili's death was the third in pole vaulting within an eight-week period - Penn State University sophomore Kevin Dare and Clewiston (Fla.) High School sophomore Jesus Quesada being the others.

While the legal ramifications of these three incidents have yet to be determined - a similar spate of pole vaulting deaths in 1997 yielded similar isolated calls for change and nothing in the way of case law - college and high school athletic administrators are considering several changes to help limit their liability.

One of the most fundamental obligations an athletic administrator owes his or her athletes is to provide them with the proper equipment for each activity - traditionally, in pole vaulting, the pole, the cross bar and uprights, and the landing pad. Since this spring's deaths, however, there has been a push by some people in the sport to mandate helmet use. While helmets may protect an athlete's head, thereby reducing one major risk, not enough research has been done to determine if wearing a helmet will actually help or hinder vaulters. For example, while helmets might prevent a head injury, helmets' added weight or bulk might increase the number of neck injuries.

Another problem with requiring helmet use is that there are currently no helmets specifically designed for pole vaulting. If an athlete wants to use a helmet, he or she must use a helmet designed for another sport, such as hockey, biking or inline skating. While these are lightweight (a consideration of great importance to vaulters), there is some question as to whether they would actually be able to protect someone from falls of 10 to 15 feet.

Pieces of equipment under closer scrutiny include poles, which are rated for a maximum weight based on how much stress it takes to bend them on takeoff. In 1995, the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) mandated that the vaulter's weight be at or below the manufacturer's pole rating. This rule is designed to prevent vaulters from using inappropriately light poles. While light poles provide more lift, they are more dangerous because they can lead to excessive bending of the pole, which makes it difficult to control both the pole and the vaulter's landing place. Lighter poles, because of their flexibility, are also more likely to snap. Coaches therefore need to become more proactive in inspecting every pole to ensure that it is rated to handle each vaulter's body weight.

Also under reexamination is the size of the landing pad. According to a study published in the January 2001 issue of The American Journal of Sports Medicine, most serious injuries to pole vaulters result when the vaulters miss the pad (as Quesada did), or when their body lands on the pad but their head hits the surface surrounding the pad (as Fili did).

Currently, the National Collegiate Athletic Association requires the pad to be a minimum of 16 feet wide by 12 feet deep beyond the vaulting box at the end of the runway. The NFHS, in an effort to cut down on catastrophic injuries, recently changed its landing-pad requirements from a minimum of 16 feet wide by 14 feet deep beyond the vaulting box to 19 feet 8 inches wide by 16 feet 5 inches deep. The NCAA is considering the same change. With the price of a landing pad ranging from $5,000 to $15,000, a lot of schools now face a decision on whether to spend thousands of dollars on new equipment.

In addition to increasing the size of the landing pad, another way to meet the duty to provide proper equipment is to cushion any hard or unyielding surfaces such as concrete, metal, wood or asphalt surrounding the landing pad. That requirement is also among the new NFHS rules changes. (For more information, see "Vault Verdict," p. 36.)

The steel vaulting box remains an area of potentially severe injury. According to the American Journal of Sports Medicine study, the second most common cause of injury in pole vaulting occurs when the vaulter releases the pole prematurely or does not have enough momentum to carry him or her into the landing pad and lands in the vaulting box. (This is how Dare died.)

While it is impossible to completely protect athletes from the risk of falling into the vaulting box, there are a couple of steps administrators and coaches could take to cut down on the risk of injury. First, schools could use box collars. The collar, which is made of dense foam padding, covers all hard surfaces between the box and the landing pad. Second, coaches might consider using spotters. The school could station two people near the vaulting box to cover the vaulting box with a pad or guide the falling vaulter into the landing pad.

Neither of these remedies are without controversy. Coaches attending a meeting on pole vault safety held in conjunction with the 2002 NCAA Division I Indoor Track and Field Championships said the box collars currently available are difficult to secure and could cause more problems than they solve. If the collar were to slip into the vaulting box, it could pose serious dangers to an athlete as he or she tried to plant the pole. As for the use of spotters, some argue that not only would the vaulter still be at risk of injury, so would the spotters - from the pole or from the impact of a descending athlete.

The issue of using spotters demonstrates how closely linked the duty to provide proper equipment is to the duty to provide proper supervision and training. Because of the dangerous nature of the activity - according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research, pole vaulting averages one death per year and has a higher rate of catastrophic injury, per participant, than any other sport - the law imposes a higher duty on coaches and athletic administrators. Proper supervision is especially important at lower levels of the sport, since that is where the majority of pole vaulting injuries occur. Again, according to the American Journal of Sports Medicine study, 78 percent of all pole vaulting injuries were sustained by high school athletes.

Although pole vaulters assume a certain amount of the risk inherent in their sport, they do not assume the risk of injury from improper supervision or training. With equipment enhancements on the horizon, it is essential that administrators place a renewed emphasis on the education of coaches, and that coaches place a corresponding emphasis on teaching athletes proper vaulting techniques.

Before rushing to discontinue or drop the sport, administrators need to balance the risk to the athlete with the organization's legal exposure. Administrators and coaches can do this by enforcing mandatory helmet use, larger landing pads and special training and certification for coaches. None of these recommendations are new - some states have already enacted, or have recently proposed, rules concerning at least one of them. But by adopting all three rules, coaches and administrators should be able to limit their organizations' liability, while at the same time make the sport as safe as possible for athletes.