Educating athletes about sexual misconduct gains importance amid recent rape allegations

Within the past 12 months, allegations of sexual misconduct - ranging from gang rape to sex with a minor - have rocked the football programs at the Universities of Colorado, Notre Dame and Alabama-Birmingham. But whether the parade of headlines represents the media's unbalanced fascination with sports celebrity or merely hints at a much deeper problem permeating the male student-athlete ranks depends on who you talk to.

"The news looks for sensational things, and right now it's a hot topic to report athletes crossing the line with their behavior - sexual and otherwise," says Joel Fish, director of The Center for Sport Psychology in Philadelphia. "I think we get an unfair perception of what football players and student-athletes are all about, because we tend to focus on the negative."

"We live in a sports culture, so it matters more if something happens involving an athlete," says Jeff O'Brien, director of the Mentors in Violence Program (MVP) offered through The Center for the Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern University. "But I don't think there's that big a difference between being a male athlete and being a male, period."

Kathy Redmond, for one, thinks there is a difference, especially for the victims of male sexual aggression. Redmond's National Coalition Against Violent Athletes was founded in 1998, seven years after she says she was raped twice by the same football player during her first week as a University of Nebraska freshman. Her alleged attacker was never prosecuted, and is currently playing in the NFL. Personal guilt and a gut feeling that justice wouldn't be served anyway kept Redmond, then 18, from aggressively pursuing criminal charges. "At first, you start saying, 'Oh, it's just sex. I'll get through it' - as bad as that sounds," she says. "I mean, I knew it would be a losing battle in Lincoln, being a Nebraska fan myself."

Many acts of sexual violence by college athletes go unnoticed nationwide, according to Redmond, who claims she faced - but didn't report - additional incidents of attempted rape while a student at Nebraska, where she played lacrosse. In talking to other victims, she found common feelings of intimidation and helplessness within a starstruck judicial system. It was this knowledge that she was not alone that led Redmond to launch NCAVA. "I wanted people to know that this happened more often than just when they read about it in the papers, that there are a lot of silent victims out there," she says.

Despite their varying perspectives, a common goal of Fish, O'Brien and Redmond is to educate student-athletes and others about the potential causes of and possible cures for sexual violence in today's culture.

Fish, a sports psychology expert whose "Reducing Risky Student-Athlete Behavior" is among the most frequently requested of 12 presentations he offers colleges and universities, emphasizes the influence of environment on human behavior. While he thinks athletes are unfairly singled out in the press, Fish concedes that they aren't necessarily like other students. "If the athlete has been put on a pedestal since the time he could pick up a ball, he can grow up with a skewed perception of what is or isn't appropriate, and whether or not behavior has certain consequences," he says.

Fish advocates positive peer pressure as a means of changing the lawless mentality that may infect, for example, a college football team. "I go through a communication paradigm called 'The Five I's: I see, I hear, I feel, I want, I will.' I see you picking up that fifth can of beer. I hear what you're saying: 'C'mon, lighten up!' I feel angry: Look at what you're doing to her. I want you to leave her alone. I will help you out of this situation - or tell the coach, if I need to," Fish says. "I have found this to be very helpful for athletes learning how to communicate their feelings at that moment, which is not an easy thing to do."

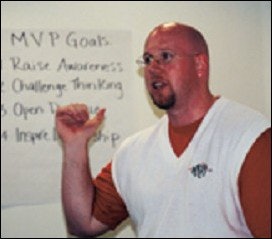

O'Brien, a former star tight end at Canisius College, brings his MVP team (comprised entirely of former student-athletes) to campuses for group discussions on how peer pressure can affect behavior, even starting at a young age. "There's a huge problem with the way boys are socialized to be men and how that lends itself to violence," he says, pointing to the ways in which "boys and men police one another to adhere to a code of what it means to be a man."

According to O'Brien, a male individual who doesn't exhibit physical, mental or emotional strength is labeled a "mama's boy," "skirt," "Sally" or some other, often cruder term - each with a female connotation. O'Brien also points out how common language choices objectify women, usually in violent ways, when men use phrases such as "nail it," "slap it" and "destroy it" during discussions about sex. Such language becomes part of the locker-room or house-party lexicon, O'Brien says, with an underlying message that women are weak. "It's not like a bunch of guys put their hands in the middle and say, 'OK, everybody disrespect women on three.' That's not the way it works."

By bringing these cultural influences from the subconscious to the conscious, O'Brien says he can help student-athletes break down potentially dangerous social norms. Like Fish, he sees peer pressure - the root of much of the problem - as a means of solving it, and the team environment lends itself as much to positive peer pressure as it does to the negative. "The focus of our work with athletes is on their leadership potential, because of their ability to create change in ways other people can't," O'Brien says. "With some of the cases being cited - and there are certainly plenty of others - I see some very poor leadership allowing that type of environment to exist."

To change a sexually volatile environment, O'Brien offers student-athletes food for thought in the hope of establishing what he calls "remedial empathy." "We'll have them raise their hand if they have a woman in their life who they care about, then imagine if somebody took advantage of her," he says. "We'll ask, 'If one of your teammates is accused of raping or hitting a woman, what does it do to the rest of your team.' - anything we can do to get people thinking about why it's important to do something about it."

Instead of providing student-athletes with a laundry list of actions they should take to prevent sexual violence, O'Brien instead asks them what they would be willing to do. Just as he doesn't preach from a soapbox during his sessions, he doesn't think it's realistic to expect college athletes to become "gender warriors" in the battle against sexual aggression. He does suggest certain techniques, however, like joining a party conversation between a drunk teammate and an intoxicated woman, as a distracting third wheel. This non-confrontational act may well succeed in preventing a rape in that one instance, O'Brien says, and honest discussion with the teammate in the days following about what could have possibly taken place may cause him to think twice the next time. "We have to get by the hesitancy among guys to talk with other guys about stuff like this in a real way," O'Brien says.

To this day, it's uncomfortable for Redmond to address a group of male student-athletes, but she says there's value in hearing from a woman what it's like to be attacked by a man. "There is a living, breathing, bleeding, crying victim involved," she says. "That's what I'm trying to get across."

In the four-year history of NCAVA, much of Redmond's energy has been focused on victim advocacy. She has helped victims find legal representation and counseling, and has provided advice on dealing with the media. "A lot of them are afraid to go to the media, and I've found that the media are very supportive," she says. Redmond, who is currently involved in five cases, also works with prosecutors, who often "don't understand the very different stakes and how you have to respond differently when a case involves somebody of celebrity."

Lately, though, Redmond has stepped up NCAVA's rape-prevention efforts. She teamed with New York-based clinical sports psychologist Mitch Abrams to create "Intercept," a presentation designed to identify and prevent aggressive responses in student-athletes, while promoting life skills such as arousal management, assertiveness training and self-evaluation.

Though the program has yet to debut, Redmond has approached officials at Colorado (where sexual assault charges were not filed in its recent alleged-rape case) and Notre Dame (which expelled those players involved in the school's third alleged-rape case in five years) about applying it to their respective campuses. "A lot of schools are afraid of my affiliation with it, because they think that I will make known to the world the information they might share with me," she says. "What they don't understand is that my goal in this whole thing is to end sexual assault."