Can athletic departments justify paying some coaches more than others? Quite easily.

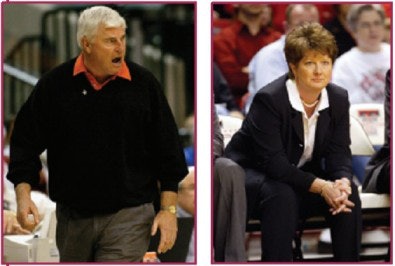

The naming of Bob Knight as head men's basketball coach at Texas Tech two years ago paid nearly instant dividends for the school. Donations to the university increased, as did the sale of tickets and licensed merchandise. Fans, meanwhile, witnessed nearly as many victories in Knight's first two seasons (45) as in the previous four (47). But the individual who may have benefited most from the hiring is Marsha Sharp, who has coached Red Raider women's basketball since 1982 and whose contract was retailored within weeks of Knight's arrival in Lubbock.

Tech officials denied any correlation, saying Sharp was due for a raise anyway - a $200,000-per-year raise, it turned out. But by matching the two coaches' contracts in length, base salary and annual deferred salary, the athletic department nonetheless put itself on solid legal ground. According to salary-equity experts, all schools should be taking a close look at their pay practices, if they haven't already. "It's not a black-and-white issue," says Janet Judge, a sports law attorney and former Harvard assistant athletic director. "When comparing jobs, levels of experience and a whole variety of different factors, you're never quite sure that you're on the right side of the law."

The law in gender-related cases comes in two forms: Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Equal Pay Act, enacted that same year. Title VII states that an individual, regardless of gender, cannot be discriminated against in hiring or with respect to his or her compensation, terms, conditions and privileges of employment. The Equal Pay Act ensures equal pay among employees who perform equal work on jobs that require equal skill, effort and responsibility and that are performed under similar working conditions.

If still unsure of what side of the law they're on, college athletic administrators now have plenty of guidance specific to their interests at their disposal, including the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's October 1997 release of "Enforcement Guidance on Sex Discrimination in the Compensation of Sports Coaches in Educational Institutions." "For just about every athletic department that I've worked with, salary equity is a concern," says Judge, who has practiced sports law for 10 years. "Most times, they will ask me to look at their current pay policies - before anything blows up. There's substantial liability out there when it comes to pay practices, because we are typically talking about a good amount of money."

As the University of Southern California found out, issues of salary equity can quickly come to a head. In 1989, first-year women's basketball coach Marianne Stanley sued USC, claiming her compensation lagged behind that of George Raveling, the Trojans' head men's basketball coach at that time (Stanley, too, has since left USC). Ten years later, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals determined that USC was justified in paying Raveling a higher wage, since he possessed more coaching experience at the time of each coach's hire. "That's a factor other than sex upon which the university relied when it set salaries," says Judge.

There are other factors that schools may rely upon, as well, from conference championships won and NCAA tournament appearances made to offices held in national coaching associations. "You might see a difference in salary between men and women coaches, but the question is whether the gender of the coach is the only variable that accounts for the difference," says Cynthia Linhart, director of Inter-Collegiate Athletic Consulting, a three-year-old firm combining higher education and sports management expertise. "We work with the institutions to identify those variables that we think, and they think, might explain the variability in salaries."

The process of identifying these variables is called multiple regression - technical-sounding terminology for what amounts to commonsense analysis. "This really isn't that difficult to figure out, and it isn't that expensive," says Andrew Fellingham, ICAC's founder and managing director, adding that a pool of 15 coaches at any given institution can be analyzed for roughly $15,000. "Number one, administrators worry about the expense. Number two, they worry that they will find something and they can't do anything about it."

For an accurate analysis of pay strategies, coaches with similar duties must be grouped. Of course, there are natural pairings (the men's basketball coach and the women's basketball coach), but comparisons can transcend the sports themselves, as long as, say, the women's field hockey roster, staff and budget mirror those of men's lacrosse, thus putting the respective coaches on similar levels of responsibility and expectation.

In fact, a solid salary-equity defense begins with properly worded job descriptions. "Many times you'll see schools that have the exact same letter of appointment for all of their coaches," Judge says. "Big mistake. Realistically, they're not doing the same thing by any stretch of the imagination. Job descriptions need to be tailored to the job."

The key is articulating the differences between the job of men's basketball coach, which may pay $850,000, for example, and the job of women's basketball coach, which may pay $175,000. Wording in the coaches' respective job descriptions should address disparate expectations in terms of ticket sales, graduation rates, revenue generation, recruiting, winning - any factor that justifies one coach's value when compared to another. Administrators need to be careful, however, not to falsely inflate the responsibility of any one coach. "What the courts are going to look at is what the person is actually doing, not necessarily what's on paper," Judge says. "If you're saying, 'Look, I'm paying the head coach of my men's basketball team an additional amount of money because he's also overseeing a facility in the off-season,' and it's discovered that the person is not overseeing that facility, that's not going to hold up."

The same goes for non-monetary compensation. If a coach enjoys perks such as a country club membership or use of a leased car, it had better be justified in job description wording. "The job description for that individual should be substantial, so that it identifies what the person has to do to earn those perks," says Linhart.

Documentation is also critical when creating opportunities for coaches to earn outside income from shoe contracts, TV and radio shows, speaking engagements or summer camps. A valid legal defense here has been that the marketplace is inherently discriminatory. Associated Press reports indicate that the only significant difference in the contracts of Texas Tech's basketball coaches is that Knight is contractually guaranteed $500,000 in outside income to Sharp's $200,000, since Knight is one of the most acclaimed speakers in college sports.

Likewise, it's Nike's legal right to choose a men's basketball team to market its products at the exclusion of the same school's women's team, but it's the school's responsibility to document evidence that it approached Nike about a women's deal, including specific dates and names of corporate contacts involved in the negotiations. Similar effort can apply to broadcast opportunities, even if it means finding a radio station with a smaller audience for the women's coach's call-in show. Moreover, a weak public speaker can be offered instruction available on campus or enrollment in a professional development course, such as Dale Carnegie, according to Fellingham, as long as the offer is in writing. "Document, document, document," he says.

"Many schools can't demonstrate that effort," Judge says. "It may be because they believed it was futile. But you're not going to have that as a defense unless you can demonstrate that you tried to do it. Provided you did, and the market did not take that opportunity, the law's been pretty clear that the school's not going to be responsible for what the market's doing. The school does actually have to go out and do some work. But from a risk-management perspective, it's well worth the effort, and it might pay off."

Of course, the ironclad compensation defense - pay every comparable coaching position the same exact salary - may not be practical. "You run into problems there if you have somebody who's much more qualified; they're going to complain and ultimately they're not going to stay," says Judge. "It's a fine line. Some schools do go that route, but I think the most important thing - and a lot of schools haven't done this - is to sit down and say, 'What is the basis of our compensation system?' "

It's a lot to consider, given the range of skill and experience of those roaming the collegiate sidelines these days. "There are a whole variety of ways that coaches work very hard to set themselves apart from other coaches, and schools look to compensate that," Judge says. "They just have to make sure they're doing it across the board." Adds Fellingham, "There are differences, and what you're doing is documenting them. That's what everybody does in every business now. And this is a business."