How should athletic administrators meet the needs of gay and lesbian student-athletes?

Dan Woog calls them the longest 10 seconds of his life. On a spring day in 1993, Connecticut's Westport News had published a column penned by Woog, a substitute teacher at his alma mater, Staples High School, proclaiming his homosexuality. "I walked into the school cafeteria later that day, and no one knew how to act," Woog recalls. "But after about 10 seconds - it felt like 10 years - the captain of the boys' soccer team came over to me and extended his hand."

Thus began the journey of an openly gay high school coach.

"One of the reasons I stayed in the closet was because of the athletes," says Woog, who took over as head coach of the Staples varsity boys' soccer team this season after spending two decades as the varsity assistant and junior-varsity head coach. "I feared a loss of respect by the kids I was coaching. I always talked about integrity and honesty - if anyone ever called his girlfriend a 'bitch,' I said, 'No, you just don't say that.' But when anyone called someone else a 'fag' or a 'homo,' I remained quiet. I was afraid people would think I was gay if I spoke up."

He needn't have worried. Thanks in part to the bold actions of a soccer player 11 years ago in that cafeteria - an athlete who no doubt held considerable sway over the opinions of his peers - Woog has helped foster an environment of acceptance at Staples.

"When I came out, I did it for the gay kids," Woog says. "But I didn't realize how important it was for the straight kids, too, because somewhere down the line, they may have a gay roommate, a lesbian boss or one of their own kids might come out of the closet. Straight kids are so much further ahead than their parents when it comes to gay acceptance. A lot of that comes from constantly seeing gay people in everything from reality TV shows to real life. These kids are not freaked out by homosexuality."

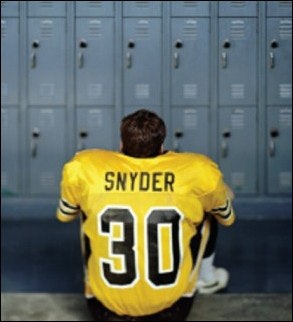

More coaches and students - but not necessarily student-athletes - are coming out of the closet, says Kevin Jennings, executive director and founder of the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN), a national organization dedicated to making schools safe for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) students. Jennings, a former high school boys' soccer, squash and volleyball coach, announced he was gay at an all-school assembly in 1988. He stopped participating in team sports in the eighth grade because of his inability to feel comfortable and safe in a team locker room, and calls that missed opportunity "the great sadness" of his high school experience. "The average age for coming out is between 15 and 17," Jennings says. "But the average gay high school athlete just sits in the locker room, keeping his mouth shut and pretending he's straight."

"Athletes will do anything they can to make sure nobody knows they're gay - from being the first to tell a homophobic joke to arranging to be caught having sex with a girl," echoes Woog, who has written six books about gay issues, including two about gay athletes. Still, he contends that some student-athletes are "very quietly" revealing their sexual identities to peer groups and others, if not to coaches and teammates. "The majority of them are in team sports like soccer and baseball, and individual sports like track, tennis, golf and swimming," Woog says. "I think athletic directors and coaches, whether they understand homosexuality or not, have to address this issue now."

According to a recent GLSEN survey of 6,201 students from 19 independent schools in 11 states, the use of slurs like "faggot" and "dyke" occurs nearly five times as often on playing fields and in gymnasiums, locker rooms and bathrooms than it does in classrooms. The disparity is even greater at all-male schools. Additionally, the survey shows that coaches and teachers seldom intervene, giving students the impression that it's acceptable, Jennings says.

That's why grassroots movements in some communities strive to help athletic directors and coaches realize that there may be student-athletes in their schools struggling with sexual-identity issues. "You've got to have a policy in place that protects gay and lesbian students and treats sexual orientation the same way as race, religion and gender," Jennings says. "And then you have to train coaches to help them understand what homosexuality is and what to do if one of their players is gay."

The Boulder Valley (Colo.) Safe Schools Coalition has made such training a priority and is becoming a model organization in the process. Not only is the coalition one of the few in the country officially recognized by local school district officials (the BVSSC is designated as an advisory committee to the superintendent's office of the Boulder Valley School District), but it's also among the first to take its message to the athletic ranks.

Last August, Corey Johnson, a former Massachusetts high school football co-captain and linebacker who revealed to his teammates that he was gay, shared his story with about 75 coaches from the district's high schools. (Incidentally, Johnson's appearance was only a few days removed from a similar event held by the University of Colorado featuring Dave Pallone, an openly gay former Major League Baseball umpire.)

"We wanted a gay high school student who could tell his story to high school coaches," says Jean Hodges, co-founder and chair of the BVSSC, as well as a former high school drama teacher and the mother of a gay adult son. "A lot of people think being gay is all about sex. But it's really about identity and young people finding themselves. That deserves to be respected."

Hodges says those coaches who attended seemed supportive. "I saw many heads nodding," she says. "There also were some coaches who I think don't believe there really is a problem. That's an attitude that's pretty common."

Several weeks later, the district hosted a three-hour training program for athletic directors run by Pat Griffin, a professor of social justice education at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and one of the leading experts on homophobia in sports.

In addition to Boulder Valley's efforts, gay advocates are cheering New York City's Harvey Milk High School. The nation's first state-accredited school for LGBT students is hoping to field teams in New York's Public Schools Athletic League this fall. Should the school succeed, supporters say the victory will do for homosexual student-athletes in interscholastic sports what Jackie Robinson did for African-Americans in Major League Baseball.

That victory, though, could also be very painful for Harvey Milk players, who may have to endure "a tremendous amount of abuse from fans," as basketball recruiting expert Tom Konchalski predicted to New York's Daily News last year.

Only eight states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Vermont, Washington and Wisconsin) protect students based on their sexual orientation. "In the absence of these policies, a lot of schools are reluctant to deal with this issue because they don't have the support of the legislature," Jennings says.

To that end, seven leading national organizations - including GLSEN, the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the Women's Sports Foundation - four years ago created the Project to Eliminate Homophobia in Sport, with the mission to teach respect for all athletes and coaches regardless of sexual orientation. Two years later, project officials launched "It Takes A Team: Making Sports Safe For Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Athletes and Coaches," a homophobia education kit that includes a video, curriculum guide, posters and stickers to help student-athletes, coaches and entire athletic departments better understand and address the needs and concerns of LGBTs in sports.

Another option in lieu of bringing in such speakers as Johnson or Griffin is a 1 7-minute video, produced by ESPN and called "Outside the Lines: The World of the Gay Athlete." The tape documents the journeys of two high school students struggling to compete as openly LGBT athletes in climates that are alternately hostile and welcoming. The video includes a viewing guide that provides lesson-plan ideas, discussion questions and other resources for building equity in athletics. Both items are available from Amazon.com.

Training of any sort can't hurt, proponents say. That may explain why the number of gay-straight alliances on high school campuses - student-initiated and student-run clubs that provide a safe, supportive environment for LGBT and straight youths to discuss sexual orientation and gender-identity issues, and to create school environments free of discrimination, harassment and intolerance - has climbed from about 1,200 less than two years ago to more than 2,000 today.

Woog likes to tell the story of a high school football coach in Orange County, Calif., whose son played for his team and then competed in the Ivy League before quitting and coming out to his father, who was stunned by his son's revelation. "If he didn't know that about his own kid, think of all the secrets other kids had that he and other coaches overlooked," Woog says. "This coach started treating players more as individuals and became an advocate for the school's proposed gay-straight alliance, speaking at a faculty meeting and an all-school meeting. It was the defining moment in that struggle." Not long after the coach showed his support, administrators approved the alliance's formation.

Other schools around the country have struggled with the decision to implement similar organizations. The Boyd County (Ky.) Board of Education opted in late 2002 to ban all "non-curricular clubs" at Ashland High School (including the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and the Pep Club) rather than allow a gay-straight alliance to continue meeting. A settlement was finally reached earlier this year requiring all student clubs to be treated equally. And in 2003, the American Civil Liberties Union and a student at Klein (Texas) High School filed suit against Klein's suburban Houston school district after it denied her and other students the opportunity to form an alliance.

Jennings sees a direct correlation between teaching acceptance, reducing the number of athletic-related hazing incidents and improving overall school atmosphere. "There is no doubt in my mind," he says, "that if coaches showed leadership on this, we'd see change."