Schools eyeing a division jump must be aware of new NCAA standards and their own shortcomings

Until this year, schools contemplating a jump to Division I-A could hardly plead ignorance of the NCAA's membership standards - they had remained exactly the same since the subdivision was established (along with Division I-AA) in 1978. But three years ago, the NCAA began mulling changes to its membership requirements with the intent, according to one collegiate athletics consultant, of stemming the tide of programs on the rise.

"Once the process began in earnest to redefine what it meant to be a Division I-A member, that put a chill on the number of people moving forward," says Bill Carr, president of Gainesville, Fla.-based Carr Sports Associates Inc., which assists schools considering a "major program initiative," as he calls it. "That was the intended effect - to slow the flow of I-AA programs into I-A."

Not so, counters NCAA Division I governance liaison Steve Mallonee. "The proposed standards will enhance the I-A subdivision while affording deserving institutions the opportunity to participate at the highest level of Division I-A competition," says Mallonee, quoting from the proposal itself.

"That's the intent," he adds. "Does it mean that by raising the standards some schools that may have been thinking of making the move may not. Well, certainly that will go into the thought process. But the rule wasn't meant to be exclusionary."

Regardless, the new rules certainly warrant pause among schools otherwise gung-ho on grabbing Division I-A's brass ring - the money and prestige that come with playing college football at its highest level. "That's an intoxicating combination," admits Carr, a former athletic director at the Division I-A Universities of Florida and Houston.

Consider the case of Florida A&M University, where trustees voted 7-5 in February to give more thought to whether FAMU should become the first historically black college to seek Division I-A status. That vote, which followed four hours of spirited debate, capped months of institutional soul-searching. The I-A proposal had held so much promise as recently as the previous June, when then-interim athletic director J.R.E. Lee III first presented it to trustees, who unanimously approved the move on the spot. But questions soon arose without definitive answers: Could the athletic department finance a program-wide jump in scholarships from 177 to the NCAA minimum 200 for Division I-A or carry a minimum $4 million athletics budget? Could the Rattlers woo at least four Division I opponents, as required by the new bylaws, to play in their 25,500-seat stadium - and do so on a mere year's notice?

"We were relatively close," says Jonathan Evans, FAMU's assistant athletic director for NCAA compliance. "We felt, though, that just meeting the minimum requirements was not where we wanted to be. When we make the jump, we want to make it to where we can be competitive and not just say that we're a I-A school."

What it takes to be a I-A school is detailed within the 20 pages devoted to membership in the 2004-05 NCAA Division I Manual. Among changes taking effect Aug. 1 is the manner in which football attendance is tabulated. Whereas Division I-A teams were expected to average 17,000 in paid attendance for each home game, they now must draw an average of 15,000 actual fans (not including vendors, players, marching band members or cheerleaders), as counted and verified in writing by a member of the school's athletics staff. "The new rules are more stringent in some key areas," Carr says. "It's a lot easier to sell a ticket than it is to have someone come through the turnstile and sit in a seat in the stadium - the difference being that you could get a corporation to buy a thousand tickets and nobody comes."

No longer are Division I-A schools required to compete in a 30,000-seat-orlarger stadium, but programs and facilities unrelated to football can still be affected by another of this year's I-A changes - the requisite sponsorship of 16 varsity intercollegiate sports, including football, up from 14.

Clearly, an athletic department's awareness of new NCAA expectations is one thing, but getting a handle on its ability to meet them is quite another. Carr identifies 17 support systems within the typical athletic department - everything from marketing and promotions to academic support to equipment. "Most often there are already deficiencies, and then we ask what would be the additional deficiencies if the school were to go to the next level? What would be the implications for the move in such areas as personnel, facilities and finances?"

This feasibility study, designed to determine whether internal support systems are up to the challenge, represents the first phase of a three-phase analysis that Carr applies to each of his upwardly mobile-minded clients, regardless of the level they're trying to reach. Phase two, a market analysis, identifies financial resources readily available through such external constituencies as ticket buyers, corporate sponsors and major donors. Schools that get this far (Carr estimates that between 75 and 80 percent of his clients do) tend to ride their emotional and political momentum on to phase three - a strategic plan of action that maps out what has to be done and when.

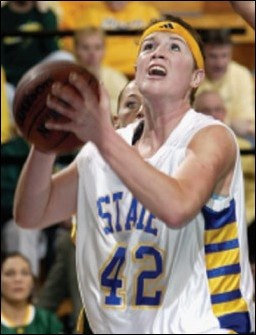

On June 30, Division II South Dakota State University completed its exploratory year, an NCAA-mandated period of transition that allows schools to test new waters without risk of penalty if they decide not to take the plunge. Fully intending to push onward, SDSU nonetheless faces an additional four-year wait before it is eligible for reclassification, during which time it may not compete for championships at either the Division I or Division II levels. "Prior to these bylaws being passed by the Division I board of directors, many of the schools that were switching from some other classification to Division I ended up being either unprepared or in a position that led to a lot of inadvertent and some purposeful violations of the bylaws," says SDSU athletic director Fred Oien. "The Division I directors felt, given their experience, that it would be helpful to go through a transition process to bring schools into compliance - to have a resting period to make sure everything was in place."

Oien's department certainly did its homework, retaining the services in 2001 of Carr's firm and another consultancy, Conventions, Sports & Leisure International out of Minneapolis, to assess SDSU's Division I prospects. Thirty-nine separate management categories were analyzed and compared against peer institutions within the Big Sky, Mid-Continent, Horizon, Gateway and Missouri Valley conferences. Household incomes and spending habits in the region were factored. "We prepared a 10year pro forma based on economic criteria," Oien says. "We projected what the scholarship needs would be every year to grow our program to fiscal year 10. We looked at what our rates of inflation would be on travel, salaries, everything. We looked at budgets that far in advance."

A remaining hurdle facing SDSU, FAMU and nearly every school eyeing reclassification is conference affiliation - finding a competitive league willing to accept a newcomer - a task made all the more difficult amid the nationwide volatility created by the restructuring last year of the Atlantic Coast and Big East conferences. Though not required by the NCAA, conference membership has become an unwritten rule of engagement. "The reality is that the industry is a cartel," Carr says. "Being in a conference gives you a guaranteed schedule. It gives you a chance to play for championships. It gives you a chance to create rivalries. In fact, the conference is integral to the industry, because it's a subset of the cartel."

But membership brings its own challenges. FAMU backed off its quest to play Division I-A football based in part on the impact conference affiliation would have on its remaining sports programs. "Our facilities - our weight room, our field house, our gym for basketball - can't compete with schools on a level of a Conference USA, for example," says Evans.

That may not be the case five years from now, Evans adds. "All we've said is we're delaying our decision. We have not implied that we're never going to do it. We just want to make sure we have everything in place to be competitive."

Though NCAA standards may in fact ebb the reclassification rush, potential financial rewards and recognition that come with competing at the next level still prove too intoxicating for some schools to resist.

There have been surprising successes: Members of one school's board of trustees heard Carr conclude his presentation to them with the statement, "I recommend you not go forward," then deliberated for all of a minute before passing a motion to go forward anyway. "They've overachieved and continue to overachieve, and we're pleased with that," Carr says.

There have also been notable failures: This March, the NCAA Division I Committee on Infractions made an example of Gardner-Webb University, which three years removed from making the transition to Division I from Division II found itself on three years' probation for major violations, including a lack of institutional control.

"This case should serve as a warning to institutions making the move to Division I that there must be a heightened sense of awareness with respect to compliance during the period of transition and such institutions need to take deliberate steps to prepare for the elevation to Division I status," notes the case summary.

For most schools, a reasonable investment in time and money (SDSU paid a combined $50,000 to outside firms) can ensure a transition is smooth, if that transition even makes sense. "We understand that other people have done this before. We should learn from them rather than make our own mistakes," Oien says. "You don't make major university decisions without thoughtful, diligent study, and you can't be afraid to spend some money to make good decisions. Had we come out of the study saying there's no way we can make it, we'd say OK. The study is still a good investment, because failure at the next level would have been expensive. But knowing that, in fact, we're close and capable of doing this ensures that we have a great future."