The landmark law is pushing 40, but how it works (and is working) remains a mystery to many.

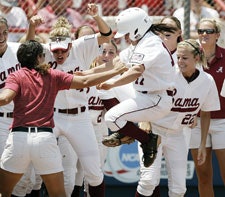

LEAPS AND BOUNDS Athletic opportunities for girls and women have vastly improved under Title IX, but gender inequities remain.

LEAPS AND BOUNDS Athletic opportunities for girls and women have vastly improved under Title IX, but gender inequities remain.Speaking at the NCAA Gender Equity and Issues Forum in April, Ellen Staurowksy asked to see a show of hands from a room full of athletics administrators, compliance officers and legal councilors. "Let's take a poll," Staurowsky said at the start of her presentation to the 60 or so individuals assembled. "How many of you have run a Title IX workshop for your athletic department?" Not a single hand went up.

Staurowsky, a professor of sport management in the graduate program at Ithaca College, repeated the question. Nothing.

"The feedback that we're getting is that athletics administrators don't want to do this, and of course part of the reason why they don't want to do this is the idea that knowledge is power," Staurowsky says. "My feeling is that the entire athletic enterprise would be much less dysfunctional than it currently is if everybody was genuinely participating in the dialogue. But the plain fact of the matter is that, from 1972 to the present, administrators haven't gotten the job done. And we know this because we continue to have enormous compliance problems."

No law has had a greater impact on the collegiate athletic landscape than Title IX, but 38 years after its passage, Title IX remains a mystery to many entrusted with its application. And that goes for coaches, too.

Yet unpublished research conducted by Staurowksy and Bowling Green State University's Erianne Weight has found that, among nearly 1,100 male and female coaches surveyed in Divisions I and III, 82 percent indicated that they had never been expressly taught about Title IX, and more than 65 percent identified the mainstream media as their primary source of Title IX information. Consequently, Staurowsky estimates that "a good 40 percent" of respondents don't know specifics of how the law works. For example, fewer than 40 percent knew that booster money is covered under Title IX.

Moreover, 82 percent of respondents admitted to not reviewing their school's Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act report on an annual basis, and some don't know what an EADA report is. Roughly one-third of the sample answered correctly that Title IX is not enforced as a quota system, but that still left a vast majority who either think it is, don't know or aren't sure. "It's that kind of stuff that really tells us a lot in terms of what coaches know and what they don't know," says Staurowsky, who was just as surprised to find that her survey numbers were consistent across gender and divisional lines.

When asked if Title IX literacy, as the study's authors are calling it, should be the responsibility of administrators more so than coaches, Staurowsky says, "Our argument is that coaches absolutely need to be literate for two reasons. Number one, because they are advocates for their programs. If they don't have a strong understanding about Title IX, then they don't have the traction to be able to effect change within their administration or to even call their administration out when it is lethargic on Title IX issues. Number two, the enforcement scheme relies on every constituency to be aware of how Title IX works, from government officials to school administrators to coaches to athletes to parents. Back in the 1970s, female athletes were learning about Title IX from their coaches. That link has disappeared. So enforcement can't just come from the top down. It can't just come as a matter of presidential decree. It's got to come from the bottom up."

Nonetheless, Staurowsky, like Title IX advocates everywhere, welcomed an April 20 letter from Office for Civil Rights assistant secretary Rosslynn Ali that pledged a commitment to "rigorous enforcement of Title IX," while withdrawing a Title IX clarification issued in March 2005 that allowed schools to use a universal online student survey (or lack of survey participation) to determine athletic interest on their respective campuses. Critics have argued that this unfairly shifted the compliance burden of proof from administrators to student-athletes.

Linda Carpenter, who with fellow Brooklyn College professor emerita Vivian Acosta, has been tracking Title IX progress for 33 years, says that this "wink-wink" approach to compliance, including fine print that essentially instructed schools on how they could delay implementation of women's teams in the face of student interest, has indeed had a chilling effect on participation numbers. The latest "Women in Intercollegiate Sport" report, released in February, is the first to show only modest gains over the two years since the preceding biennial report. Likewise, little if any change was evident in the areas of head coaching, athletic training and sports information, where women have long remained underrepresented. (The numbers of women in both paid administrative and assistant coaching positions are at all-time highs.)

Carpenter doesn't discount economic influences, and she says how schools budget for athletics will have as great an impact on gender equity in the coming years as the OCR's rededication to enforcement. "This is a true test, I think, of an institution's commitment to the role of athletics on campus," she says. "If administrators are holding football free from budget cuts and cutting men's quote-unquote minor sports and women's teams, then that says that they - from my point of view - don't get it, and perhaps they never will. It's not about a Saturday spectacle. There are other reasons that athletics belong on campus."

Without Title IX, Nancy Hogshead-Makar, who at age 14 was the world's top female swimmer, would not have received a college scholarship. Her competitive career may well have ended before the 1984 Olympics, where she won three gold medals. And hers was a relatively gender-neutral discipline. "I was in a sport that is as equal as they come. We swam lap for lap, we lifted weight for weight, we were all in the pool together. It's pure merit," says Hogshead-Makar, a part-time professor at Florida Coastal School of Law and the newly minted senior director of advocacy for the Women's Sports Foundation. "I think that's why so many gender-equity advocates come out of swimming, because we can't imagine it any other way."

Helping bring others around to that way of thinking is a growing body of research on the benefits of athletics for women. Both Staurowsky and Hogshead-Makar cite the work of University of Pennsylvania economist Betsey Stevenson, who has shown that roughly 20 percent of the increase in women's education and about 40 percent of the rise in employment for 25- to 34-year-old women can be linked to Title IX and team sports participation. "Her Life Depends On It II," a Women's Sports Foundation study co-authored by Staurowsky, credits girls' adolescent sports participation for mitigating risks of osteoporosis, breast cancer, heart disease and other adverse health conditions later in life. "Obviously, it's done a tremendous amount," says Hogshead-Makar of Title IX, having argued cases on behalf of softball players as a private law practitioner. "But we still have a long way to go."

In an article titled "Are We There Yet?" published last year in Academe, Carpenter and Acosta essentially answer, "No." "We've gotten closer," Carpenter says. "We've crossed a lot of milestones, made a lot of correct turns. But we're not there yet. And we're not going to get there unless the role of athletics is altered some." That might entail, among other things, bringing the mega salaries of male coaches more in line with the compensation of college presidents, according to Carpenter. "When will we know if we're there yet?" she asks. "One of the signs would be people talking about support for athletic teams rather than for a particular team, so that the boosters' loyalty is program-wide and they see the benefit of athletics in the lives of people - not just in the lives of boys and men, but in the lives of girls and women."