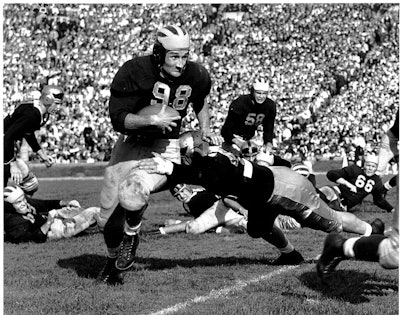

Old-fashioned "leatherhead" football helmets from the early 1900s are often as effective as - and sometimes better than - modern football helmets at protecting against injuries during routine, game-like collisions, according to Cleveland Clinic researchers in Ohio.

A study published online last week by the Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine compared head injury risks of two early 20th-century leatherhead helmets with 11 top-of-the-line 21st-century polycarbonate helmets. In their biomechanics lab, Cleveland Clinic researchers conducted impact tests by crashing helmets together at severities on par with 95 percent of on-field collisions (75 G-forces or less) in collegiate and high school football games. For this study, researchers analyzed hits common in games and practices - ones that taken separately may not seem perilous, but when added together may lead to serious long-term injury.

For many of the impacts and angles studied in the lab, researchers found that leather helmets offered similar, or even better, protection than modern helmets.

"The point of this study is not to advocate for a return to leather helmets, but rather to test the notion that modern helmets must be more protective than older helmets simply because 'newer must be better,' " says lead researcher Adam Bartsch, director of the Spine Research Lab in Cleveland Clinic's Center for Spine Health. "Unlike cars, in which seat belts, airbags and crumple zones make the choice between a 1920s Model T and modern minivan a no-brainer, these results tell us that modern helmets have ample room to improve safety against many typical game-like hits."

11_leatherhelmet.jpg

11_leatherhelmet.jpg

According to the Mitchell & Ness Nostalgia Co.'s website: "The leather football helmet was first worn in an 1893 Army-Navy game. A shoemaker from Annapolis created the first helmet for Admiral Joseph Mason Reeves, who had been advised by a Navy doctor that he would be risking death or 'instant insanity' if he took another kick to the head. Some of the first 'helmet' designs were held to a player's head by three heavy leather straps fashioned by a harness maker, which in turn, gave the first football helmets the nomenclature 'head-harness.' ... Helmets were not mandatory until the 1930s. Most of the games played between 1890-1915 were played without helmets. It was common to see some players with helmets and some without. Around World War I, helmets were so flimsy they were often mistaken for aviator caps. As years went on, more and more padding was added."

Cleveland Clinic researchers note that helmet safety standards (as measured by the Gadd Severity Index) are based solely on the risk of severe skull fracture and catastrophic brain injury, not concussion risk. So while modern helmets may prevent severe head injuries, this study found that they frequently did not provide superior protection in typical on-field impacts when compared to leather helmets. The findings suggest that helmet testing should focus on both low- and high-energy impacts, not solely on potentially catastrophic high-energy impacts. This is especially true of youth football helmets, which are currently scaled-down versions of adult helmets. The lack of adequate knowledge surrounding adult helmet protection at low-energy impacts - as well as the current absence of any youth-specific helmet testing standards - may have serious brain-health implications for the three million youths participating in tackle football in the United States each year, clinic researchers say.

The leatherhead study is one of several projects Cleveland Clinic is undertaking to better detect and prevent brain injuries across a wide range of sports, including football, boxing, hockey and soccer. Teams of researchers are working to make safer youth football helmets (through a grant from NFL Charities), create an "intelligent mouthguard" that measures the number and severity of hits to the head among athletes, produce a blood test that can diagnose concussions and develop an iPad app that uses the device's built-in gyroscope to quantitatively capture pre- and post-game measures of balance, memory and cognition.