Last February, New Hanover (N.C.) High School escaped a second-round upset bid by Knightdale in the boys' basketball playoffs courtesy of a last-second shot that broke a 53-53 tie, but that wasn't the only drama associated with this hotly contested game. Spectators entering the game had to go through a metal detector, a move that was necessitated by a 15-year-old student bringing a .22 caliber handgun to New Hanover's first-round game against Ashley High School. The walkthrough metal detector was set up shortly before the game, replacing police offers using handheld detectors. As New Hanover athletic director Keith Moore told StarNews of Wilmington, "I'd rather be safe than sorry."

A January 2013 survey conducted by the North Carolina School Boards Association examined the state of security in high schools in the wake of the events in Newtown, Conn. According to the survey, 55 school districts (out of approximately 115) are using metal detectors, but five of those districts only have metal detectors at their alternative schools, and 15 districts are only using metal detectors at one or two schools. Meanwhile, nine districts use metal detectors exclusively for their athletics or special events.

"Not today, not the next six months, but the increase in entrance screening on the high school level is inevitable," says Luca Cacioli, director of operations for Twinsburg, Ohio-based security screening company CEIA USA.

Entrance-screening technology has become common on the professional sports level (see "Perimeter Defense," Sports Venue Safety, July 2014), and collegiate sports venues are increasingly implementing some form of entrance-screening technology. So why has the interscholastic level been so much slower to adopt this important security tool?

FANDEMONIUM

Today more than ever, teams and schools are prioritizing the gameday experience and how they can improve that experience for fans of all ages. The concern on the school level is that implementation of security measures such as metal detectors would create a potentially hostile environment for fans faced with long lines and inappropriate searches prior to entering a venue, but screening technology today is such that long lines during any type of inspection can be easily avoided.

"Walkthrough metal detectors can get 600 to 700 people through in an hour, compared to the 30 seconds per person it traditionally takes for handheld detectors," says Cacioli, who also points to the discriminatory factor of today's walkthrough metal detectors as why this process moves much faster. Walkthrough screeners can be programmed not to go off when scanning innocuous items, such as watches, rings, shoes or belt buckles, while still focusing on dangerous items, offering an advanced level of functionality that handheld wands cannot. "Smart" functions also include seeing how many people are going through each metal detector to determine which metal detectors are being underutilized and then adjusting staff accordingly.

Andrew Goldsmith, vice president of global marketing for Rapiscan Systems, a security screening company based in Torrance, Calif., understands the concerns schools may have in terms of entrance- screening technology hurting the fan experience, but he stresses the importance of making the process as unobtrusive and efficient as possible.

"The most important thing is training the people who are operating the systems on how to use them properly and setting up a good process where, if there is something questionable that comes up and the system does alarm, you get that alarm resolved quickly," he says. "People don't necessarily always think through — once they find something — what they are going to do and how they are going to deal with it quickly."

Jay Hammes, retired head athletic director for the Racine (Wis.) Unified School District and president and founder of Safe Sport Zone, an organization that assists high school administrators in mitigating risk and liability at their respective athletic events, believes the true difference-maker is that human element.

"People detectors are better than metal detectors, and having your administrators and law enforcement officials at the gate watching for suspicious behavior can prevent problems later in the event," says Hammes, who also professes his support for schools utilizing some form of entrance-screening technology.

Cacioli knows the interest is there on the high school level, but there are elements at play beyond simply budget constraints. "I've heard numerous times that the schools want to utilize entrance-screening technology, but the parents don't, so in order to not upset anybody, they don't do it," he says.

While this sentiment is applicable to suburban schools, many urban schools and school districts have been quicker to adopt this security process due to gang-related activities and other problems associated with that environment.

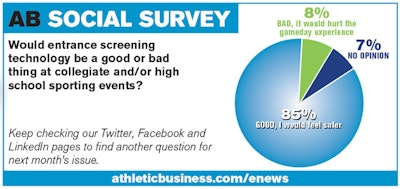

AB enews social survey

AB enews social survey

(SUB)URBAN COWBOYS

One of the interscholastic security pioneers in the United States is Patrick Fiel, a 22-year veteran of the Military Police Corps. Fiel, founder of PVF Security Consulting, previously served as the director of security for 150 Washington, D.C., public schools, where he was tasked with protecting their 70,000 students and 8,000 teachers, administrators and employees. He overhauled the city's security approach, dramatically reduced the incident rate, and received approved increases in budget for technology by a factor of five. Those technology enhancements included the implementation of handheld metal detectors from Garland, Texas-based Garrett Metal Detectors, as well as X-ray screening machines from Rapiscan.

"It's important that metal detectors not only be calibrated to focus on objects over a certain type or weight, but have very low false alarm rates," says Goldsmith, whose company has a strong high school urban install reach outside of Washington, D.C., including New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. "In urban environments, we do see a lot of demand for screening technology. Outside of those school districts, there hasn't been as much demand, but it makes sense — nobody wants to think about the problem."

A big part of Hammes' screening plan on the high school level is requiring all fans to show some form of photo identification before entering an event, which would be applicable to high school students and adults only. Middle school and elementary students would be required to be accompanied by an adult.

"Before I retired, we would host many state sectional final games in boys' basketball, with the winner going on to the state tournament," Hammes says. "The crowds were normally sellouts, and we had to screen thousands before they could purchase their ticket. We targeted eight seconds per person and never deviated, even when the rush came. All spectators showed a photo ID and participated in a visual search with a handheld metal detector scan.

"We never experienced a problem at our games. I guess the results speak for themselves."

This article originally appeared in the September 2014 issue of Athletic Business under the headline, "Scanning the Defense."