Managing crowd behavior is an inherently complex task, but understanding the basic principles that underlie individual decision-making gives us a significant advantage when designing and executing fan violence prevention efforts.

It's important that we recognize that humans are products of their environments. The great thinkers of the Enlightenment period suggested that while we are free to choose any course of action, people tend to make decisions that maximize pleasure and minimize pain. More recent research has shown that our attempts to experience pleasure and avoid pain are heavily influenced by our perceptions of the immediate environment. In other words, we make choices based on what we see happening around us.

Environments give off powerful behavioral cues. These can be physical. Stanchions placed in a bank lobby tell us that we must form a line before receiving service. Patrol cars strategically placed along the roadways encourage us to slow down and adhere to speed limits. Shell casings lying along a graffiti-riddled alleyway tell us to move quickly through the area or turn back around.

Cues can also be social. We are likely to start running if we see others running away from some unknown approaching danger. Students studying silently in a library remind us to whisper. We can be interrupted by a stern look from a respected elder. Everyday decisions and actions are, in large part, made in reaction to what we experience in our daily environments.

But people do more than mindlessly react to or simply mimic what others are doing around them. They deliberately choose a course of action. Even when making a split-second decision, our choices are the product of a personal cost-benefit analysis. Ronald V. Clarke, a crime scientist, expanded upon this rational choice theory to help us better understand why people are likely to choose one course of action over another. Clarke's model is called Situational Crime Prevention, or SCP.

When picking a course of action, people use the physical and social cues in their environments to answer the following questions:

• How much effort is needed to do this? Is this the easiest course of action?

• What are the risks involved? Will I be detected or harmed?

• What are the rewards? Are the benefits worth the effort needed and risk involved?

• Do I feel provoked? Will this satisfy an immediate or pressing need?

• Can I excuse my behavior? Will I be able to justify my behavior to others and myself?

According to the SCP model, people are more likely to engage in behaviors that involve little effort and risk while offering high rewards. They are also more likely to act if they feel provoked and can easily rationalize their course of action. In many instances, alcohol can play a role and cloud an aggressor's mental calculus, but ultimately misbehaving individuals are responding to cues in their immediate environments.

FIGHT OVER FLIGHT

No matter how crude the cost-benefit analysis, their assessment of the five dimensions of effort, risk, reward, provocation and excuse make engaging in physical contact and violence seem like more attractive options than walking away.

During a fight, it can be hard to understand why some people do nothing when innocent parties are being attacked or put in danger. Some people simply attribute this behavior to mob mentality, but that would be an unsophisticated and incomplete explanation. A more accurate description of the dynamics involved in this complex phenomenon draws again from the SCP model.

Crowds, by their very nature, create dangerous dynamics. Most crowd structures provide cues that make aggressive and destructive behavior seem like a more attractive option.

To explain this, first consider how crowds tend to provoke violence. While a sold-out or oversold sporting event increases profits, highly dense crowds also increase unwanted physical contact between strangers. They increase wait times, thereby increasing frustration and stress. Dense crowds can also make movement difficult. In emergency or mass-panic situations, this can lead to swarming and crowd crushes, which often result in severe injuries or death.

Large crowds also make engaging in violence easier, less risky, more rewarding and excusable. Having many people around makes it easier for me to find help if I want to jump over a wall, light a match to start a fire, or have someone purchase alcohol if I'm underage. Crowds also reduce perceptions of risk by providing cover. I may think it will be easier to conceal my identity or slip away when surrounded by a large group of individuals. Or, I may feel more confident in confronting others if backed by a group of friends.

If my goal is to injure many people, a crowd is a rewarding target. If my goal is to attract attention, a crowd that reacts positively to my disobedience serves as my reward and can encourage further misbehavior.

Finally, I may find it easier to excuse my behavior in a crowd, particularly if I can point to several others who were engaged in the same behavior.

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

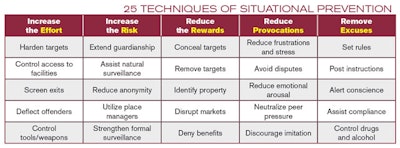

Although crowds naturally create dynamics that can make violence seem more attractive, it is possible to manipulate environmental cues in venues to make violence a less-attractive option for all attendees. We can do this using the SCP model, which offers 25 different prevention techniques — five techniques for each perceptual dimension. Our goal is to make violent behavior more difficult and risky and less rewarding, while eliminating provocations and removing excuses. We can make these changes by placing (or removing) specific environmental cues in our venues.

Do the following to develop your own prevention plan using the SCP model:

1. Select a specific problem. Fan violence at the entry gates may require a completely different prevention strategy than fan violence in seating areas. You can conserve resources and develop more effective strategies by focusing on one well-defined problem at a time.

2. Produce a list of all possible interventions. Use the 25-techniques table above to generate ideas and develop creative solutions to your problem. Don't worry about feasibility at this stage.

3. Select the most-promising interventions for implementation. Budget and resource limitations will likely prohibit the adoption of 25 different interventions for any one specific problem. When selecting your final list of interventions, try to focus on those that are new and innovative, and ensure that you target as many as possible.

Knowing your audience is critical in the crowd-management business. What works for a concert may not work for UNLV Rebel Basketball fans. But the basic principles of human behavior remain the same. Knowing how people perceive and react to their environments gives us an edge. Our task is to insert the right cues in the right places to encourage safe fan behavior.

Tamara D. Madensen is an associate professor of criminal justice and graduate director at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She currently serves as the director of UNLV's Crowd Management Research Council. This article originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of Athletic Business with the headline "Mob Mentality."

A Case Study in Crowd Management

Crowd dynamics can be dangerous. No one knows this better than Rick Martinez, a former NYPD officer currently serving as the senior operations director at the Bethel Woods Center for the Arts in New York. This 15,000-person-capacity venue was built on the site of the historic 1969 Woodstock festival and hosts a variety of events, including concerts. One night in August 2011, an incident at one of those concerts left Martinez temporarily paralyzed from the neck down.

As people were leaving the venue, a fight started after one man attacked another for inappropriately grabbing his female companion. When Martinez arrived at the scene, a large portion of the people surrounding the two men had joined in the brawl. He spotted an older security guard who had fallen to the ground and was being pummeled by the crowd. Martinez jumped in into the melee to pull the guard to safety. Someone, who was never identified, approached from behind and struck Martinez in the back of the head, rendering him unconscious.

Although the effects of alcohol might have clouded their mental calculus, these individuals were responding to cues in their immediate environments. What might be more difficult to understand is why so many others who did not know these men decided to join the fight, or why someone would attack Martinez as he attempted to rescue another person.

When Martinez began to prepare for the same artist's return to Bethel Woods two years later, he wasn't taking any chances, putting in a variety of new security measures (see graphic). As shown, Martinez greatly altered the environment, even before fans entered the venue. These cues changed the crowd dynamic as expected. Only a few minor incidents occurred, and no serious injuries were reported.

RELATED: Managing Bad Parental Behavior at High School Games