Risks at sporting events such as active shooters, bomb threats and fan violence can all be lessened through proper security measures, ensuring a safer sporting event. However, another essential component of emergency action planning — severe weather — is harder to avoid.

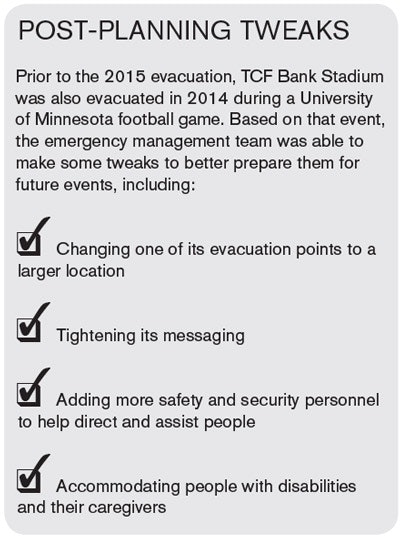

Thankfully, it's also easier to predict and prepare for. Last August, severe weather threatened a Minnesota Vikings preseason game at the University of Minnesota's TCF Bank Stadium. First, patrons were held on the concourse or prevented from entering the stadium during warm-ups. Then during the second quarter, lightning prompted a full-scale evacuation.

"As part of our standard operating procedures, we have a command structure in place that includes a meteorologist on scene," says University of Minnesota department of emergency management director Lisa Dressler. "The NFL also has its own meteorologist in New York. We had been monitoring the weather. We had a conference call with all of our partners earlier in the morning about preparing for a possible evacuation."

Preparing for severe weather starts with the creation of a solid emergency action plan, but success depends on the preparations taken in the days and hours leading up to an event, relying on clear communication both internally among the event team and externally with the public.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

ANTICIPATING THE STORM

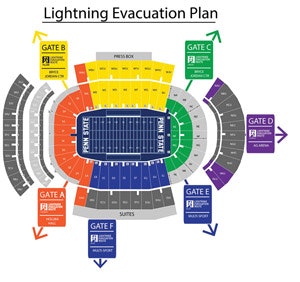

The impact of severe weather depends on the size and location of the event. Outdoor football games tend to be most affected, so much so that in 2014 Penn State University formed a Continuity Planning for Foul-Weather Football Games Committee.

Comprised of representatives from the athletic department, the office of physical plant, the department of policy and public safety, the transportation services department, the office of strategic communications and the office of risk management, the committee prepares not just for a potential evacuation but all the ramifications of severe weather.

"Our parking lots are mostly grass," says director of emergency management Brian Bittner. "We work with the grounds crew to determine what we want to have closed and open. One, we want to protect the fields, and two, we want to make sure we're not putting anyone in harm's way by having them in muddy driving lanes."

The morning of the Vikings preseason game, representatives of the team, the NFL and the university sat down to discuss their plan of action. "The NFL and Vikings were really great, listened to the university about what we thought should take place and followed our lead," says Dressler.

The National Center for Spectator Sports Safety and Security recommends identifying in advance who has the authority to make the decision to relocate spectators, and how it will be communicated. At Penn State, that includes members of the task force as well as the university president, athletic director, assistant athletic director and senior vice president for finance and business. "They have a room set up on their side of the stadium, and they're all located in relatively the same area," Bittner says. "We page them, and they can get together in under a couple minutes for a conference call."

In addition to internal discussions, external communications should also be preparing spectators for the possibility of severe weather. "We worked with the Vikings' public relations personnel and our own to get information beforehand to prepare the crowd," Dressler says. "We noted the different evacuation locations for sheltering, the sheltering-in-place component. We continued to message on the big screens and video boards on the concourse, showing maps and radar, and keeping people up to date on the weather."

Even when severe weather doesn't spark an evacuation, spectators should still be kept abreast of a storm's status. "We had a close call where a storm was going to skirt around the area," says Bittner. "We made an announcement, 'You may see lightning in the distance, but we don't believe it's headed toward the stadium. If anything changes, we will advise you.' And we left it like that. It was pretty well received."

EXECUTING AN EVACUATION

Once a decision to evacuate has been made, the real work begins. Spectators need to know where to go and how to get there safely. Penn State relies on surrounding athletic buildings — a basketball arena, a hockey arena, an intramural facility, and even a horse arena. "We utilize a lot of different buildings, and we were really creative on finding room," Bittner says. "Other stadiums have the ability to put all of their patrons under cover in the stadium — baseball stadiums in particular are good at that."

TCF Bank Stadium uses a combination of onsite and offsite shelters. "We use signage throughout the stadium showing offsite shelter locations," says Dressler. The stadium recently earned recognition as a StormReady venue, a certification created by the National Weather Service. "The department of emergency management worked with our athletic department, the National Weather Service and the police department to gather the necessary information," Dressler adds. "The NWS did a tour of the stadium, we met at their offices, provided all of the facts on the building and showed them what it is that we do."

NCS4 recommends utilizing an evacuation simulation program, consulting the Department of Homeland Security's Stadium Evacuation Guide among other resources, as well as training and practicing in advance with safety and security personnel. The International Association of Venue Managers also offers a one-day Severe Weather Preparedness Training program.

A combination of video board signage PA announcements, verbal guidance by public safety personnel, social media and text alerts should be used to help steer patrons to the proper exits and shelter locations. "One thing that works well is to have the standard PA announcer announce over the air what is taking place," Dressler says. "People respond better to hearing the same voice relay that message instead of a new voice or person telling them where to go."

One of the biggest challenges to evacuations during severe weather is actually convincing fans that there is a threat. "If we have to evacuate Beaver Stadium, we need to start 40 minutes prior to the arrival of the storm," Bittner says. "You're sitting in a section of the stadium and see clear sky, and the voice of Beaver Stadium comes on and says you need to evacuate. But you paid $50 a ticket and see clear sky."

A best practice recommended to Bittner and used by other venues is to broadcast a radar map on the venue's video board. "We have a plan to put up the radar to show the storm and how it's approaching Beaver Stadium as a way to emphasize to folks that it's real, we're not making it up," Bittner says.

During its evacuation of a Gophers game in 2014, Dressler's team shared the radar map with spectators in anticipation of an evacuation. "People were watching the radar, and a lot of them self-evacuated," she says.

RETURN TO PLAY

Once the threat of severe weather has passed, venue staff member need to have a plan ready to get patrons back to their seats. "At our different sheltering points, we have video boards that mirror the boards in the stadium," Dressler says. "Once we had the all-clear and knew that we'd allow people back in, we had our public safety personnel share that info and put it on the boards."

For facilities without the ability to shelter in place, this can be an arduous task. "We would have to do the same kind of entry as we did previously," including bag checks, says Bittner.

The action plan at Beaver Stadium includes communication with the key decision-makers as well as NCAA game officials. "I don't think they'd ever do this, but the officials can stage the game without the fans," Bittner says. "So we have to coordinate with them to see what time they want to resume, make sure they're getting the same all-clear that we are, and that gives us an idea of how long we have to get fans back into the stadium."

A NOTE ON SMALLER EVENTS

A football game with thousands of people in attendance is the biggest event an athletic department needs to be prepared for, but it's not the only one. Evacuating a few hundred people at a soccer or lacrosse game is a much simpler task, but a plan still needs to be in place. There's no operations center, no meteorologist onsite, no team of athletic executives waiting.

For smaller events, athletic departments can still work with their local meteorologist or NWS branch to receive warnings and alerts, though an onsite presence may not be called for. Athletic trainers and coaches can also take advantage of apps to stay in tune with the changing conditions. "Our athletic trainers all have an app on their phones, and if there's lightning within a 10- or 15-mile radius of wherever they're standing, it sends them an alert," Bittner says. "So if you're at the lacrosse field, you've got a crowd of 500 and two teams, a couple people get the alert and start making phone calls to determine if they need to clear the fields."

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2016 issue of Gameday with the title "How to prepare for the threat of severe weather at a stadium "