Some argue that the game of football would be safer without helmets, reasoning that players would be less likely to lead with their heads when tackling, and thus sustain and inflict fewer head injuries. There might be some merit to this thinking, but consider American football's meager beginnings at the turn of the 20th Century when the game was played without any head protection at all.

Back then college football was plagued by so many injuries and deaths that President Theodore Roosevelt wanted the sport discontinued. At the White House's behest, a group of 62 institutions of higher education came together in 1905 to address the problem and formed the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, which in 1910 would become the NCAA. The association introduced the forward pass, as well as leather helmets to the game of football. The forward pass helped spread the field, thus reducing the number of high-impact collisions, while the leather helmet was the first piece of equipment aimed at protecting players' heads.

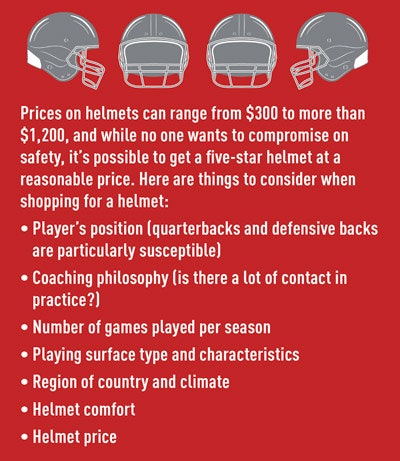

Without a complete overhaul of the game Americans have come to know and love (though overhaul remains a distinct possibility), helmets will remain an essential part of every player's equipment. Here's a quick primer on the evolution of the modern football helmet, as well as what to look for if you're in the market for new headgear.

Helmet evolution

Helmet technology has come a long way since the early 20th century but not necessarily at a breakneck pace.

"Helmets from the early '80s to, say, 2000 didn't really change much. That's 20 years of helmet technology," says Barry Miller, director of Outreach and Business Development for the Biomechanics Lab at Virginia Tech, which produces a comprehensive, unbiased helmet rating system for the youth and high school/college markets. "They tried air, they tried gels, they tried different padding, different materials, but by and large, it was pretty much the same helmet."

Today, however, heightened awareness of the long-term effects of traumatic brain injuries has spurred innovation in the helmet industry. The shape of the shell has changed, with contouring around the base of the head on most models. The plastic around the jawline has been extended on some models, and a flap-like cutout on the crown of the head on certain models allows for more give upon impact.

"Even in just the past five years it's been a dramatic difference," Miller says, adding that Virginia Tech's helmet rating system has tried to guide parents, coaches and players toward the best protection. The ratings themselves offer more granularity and insight into the effectiveness of the helmet at protecting players from concussion.

While every helmet in the United States has to meet some sort of standard, most standards organizations offer a pass/fail certification, which most of the time is based on whether it protects the skull from fracturing. "So, you as the consumer, if you're picking a helmet off the shelf — both of them are certified because they're allowed to be sold," Miller says. "Then, after that, what do you do? Well, you kind of go by the way it looks. Maybe the price tag? And then you pick a helmet, but you're not really picking it on any independently rated criteria. That's where we fill this huge void."

New technologies

The Biomechanics Lab at Virginia Tech actually gathers information from sensors that are embedded in helmets during games and practices, as well as impact tests done in the lab. The data has helped researchers and helmet manufacturers better understand what's actually happening to both the helmet and the brain during an impact — information that should lead to better, more effective helmet technologies.

Miller explains that the brain sits inside the skull, essentially floating in cerebral spinal fluid. He likens what happens inside the skull during an impact to the forces acting on a carton of milk. If you were to slide the carton of milk in a straight line across a plane and then abruptly stop it, or twist the carton, the milk inside sloshes around.

"Concussions are caused by that stress and strain of the brain trying to maintain its position inside of the skull," he says. "It doesn't have to hit the side of your skull. It could and that would probably be a little bit more traumatic than a normal concussion. But in the end, it's the stress and strain on the brain trying to maintain its position inside the skull."

This all happens very quickly — in about three milliseconds. By comparison, a blink of the eyes is about 30 milliseconds. What helmets are trying to do is buy the end user more time. "It's really a challenge for a helmet to reduce those head accelerations in such a fast impact, but that's the goal of the helmet — to slow your head so that you don't have these abrupt changes in acceleration or deceleration," explains Miller.

New technologies being developed aim to redistribute the force of rotational or linear acceleration. Miller says new "slip technologies," which aim to allow the end user's head to move independently of the helmet, are one promising development in helmet design. "Really, if impact is farther away from the center of mass of your head, you're going to have a lot of rotational kinematics," he explains. "So what this slip technology allows is for your head to maintain a little more position and buy you a little bit more time."

Miller expects to see more rotational-mitigating technologies incorporated into football helmets going forward. "What if you had a two-piece helmet, so the upper part of the helmet is allowed to move independently of the lower part?" Miller posits. "Usually you get hit somewhere above your ear line, and if that helmet was allowed to move independently of the lower part during an impact, that might mitigate some of those rotational forces, as well. And maybe it's not just a two-piece helmet. Maybe it's a five-piece helmet."

Check the ratings Virginia Tech's helmet ratings have become the go-to reference for coaches, parents and athletic directors wanting the best protection for their players. However, Miller says it's important that people understand how the system actually works, as the final ratings report offers both a Star Rating (out of five stars) and a Score. All of the 10 best helmets in Virginia Tech's ratings received five stars, however the scores on those 10 helmets vary.

"You want a low score," Miller says, explaining that the score indicates the average number of concussions a player would get while wearing that helmet if they were exposed to 420 seasonal impacts — the average for a full season of practices and games, as determined by the lab's own data.

"If you're comparing helmet A against helmet B, you would subtract the lower score from the higher score and then divide that number by 420," Miller says. "So those percentages are going to be really low, but I always tell the parents that there's a practical side to that. So maybe the percentage is 2 percent. Well, 2 percent might be two concussions, but those two concussions might be too many concussions."

This article originally appeared in the November | December 2019 issue of Athletic Business with the title "Football helmets past, present and future." Athletic Business is a free magazine for professionals in the athletic, fitness and recreation industry. Click here to subscribe.