Beginning with a concept and working toward a completed facility project, along the way there are some essential steps which must occur before the doors to your new facility can be opened. After selecting an architect, performing a needs analysis and determining the functional spaces necessary, there are seven additional steps which must follow immediately thereafter.

From AB: From Concept to Completion - Sutton Center

In this article, we’ll discuss two of the final seven: Master Planning and Schematic Design. In subsequent posts in this series, we’ll cover design development, the creation of construction documents, bidding and negotiation, construction and the post occupancy checklists.

Master Planning

Every traveler needs a map. Such a roadmap will provide a full coast-to-coast view of the landscape before them. When opening this map, each conscientious leader will determine the best course to take in order to get to the final destination safely and under budget. When multiple travelers are setting out from the same origin, on campus or elsewhere, attempting to head in the same direction, there needs to be a master plan. A master plan will not only allow each traveler to see how they fit into the grand scheme of things, but ensures building efforts will not be duplicated, resources will be closely aligned and unity will be the result. Without a master plan for your facility, there is a possibility facilities could be created without a sense of the whole. The development of a master plan in the early stages of the building process will align university units increasing the probability that all will move in unison in the same destination.

Master Planning is a comprehensive vision that helps your facility fit within the university’s master plan. It is a tool to sequentially guide all future development. It serves as guide to growth over time. A master plan is a long-term view extending out oftentimes 10-15 years down the road. The plan should not be static, but a living document continually updated so that it can keep abreast of recent trends in usage and facility operation. It should not be an exercise experienced by only a few, but a collaborative effort involving key stakeholders. A master plan gives direction to the design team. It is a deliberate pathway for all to see, understand and follow. It ranges from the broad vision to the itemized sequencing of phased improvements with cost estimates for each phase. It is accessible and easy to understand so that all can see where we are going as a department and a university.

After an alignment is made with the university’s or city’s master plan, there are two basic types of master planning which need to be performed relative to your facility project. One is general, and the other is building-specific.

In the general site master plan, writers of the plan most often discuss broad sweeping items such as the massing of facilities, access and transportation specifics to the site, connections to services and utilities and zoning restrictions.

When considering the building-specific master plan, the main thrust will be a focus on the sequential priorities of developing the site. If phasing is a project consideration, it will be covered in the plan. This building-specific master plan will include: proper zoning, historical land use policies, building height, setbacks and easements, parking requirements, downstream impacts, off-site disposal of excavated material and an environmental impact assessment looking at soils/water pollution, noise generation, architectural history and air quality — to name a few.

With the architect and consultants on board, the needs determined by patrons and operators and the programming of functional spaces thoroughly communicated, a master plan must be developed. The master plan must not only show your facility’s growth over time, but your facility must fit into the overarching master plan of the whole campus or organization.

Schematic Design

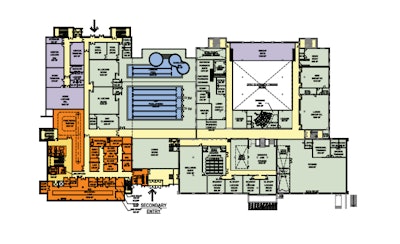

Once a comprehensive listing of functional spaces has been gathered, the selected architectural firm will retreat to their drafting rooms to create the first set of schematic designs. During this time of intense review, they strive to interpret what they have just heard and seen.

From pages and pages of notes, recordings and interviews, the architects seek to define what they feel is the essence of the scope of the project desired. With their staff expertise coupled with the technological tools of the day, the architect will then aim to illustrate their interpretation through a variety of architectural techniques. Through multiple delivery systems, the architect designs clear images in order for the client to visualize what the future space will look and feel like for their patrons. If successful in this process, the client will fully understand the architect’s view on the program’s main components ranging from materials used to the adjacency of spaces.

The most commonly used mediums through which architects define and illustrate their interpretation of a concept is through rough drawings and computer-assisted renderings. The conceptual sketches may include site plans, floor plans and building sections and elevations. The computer illustrative materials may consist of 3D views, colorful renderings and miniature hand-built models of the facility.

Schematic design is not a one-and-done process. It is an iterative and interactive process where communication between the client and the architect is on-going. Each sketch will respond to the list of programmed spaces. Once the objective of defining the scope, the size of the footprint, the functional relationships between space and traffic flow have been illustrated, a tentative schedule, construction budget and contingency is initially put forth. After all ideas have been shared, reviewed, revised and carefully considered, the best concept is selected to go into the next phase, design development.

In order to provide knowledge-based feedback both in master planning and schematic design discussions during Concept to Completion, it is extremely important that we know what has been done elsewhere. This is where it is important to do site visits of newly constructed facilities directly related to your project.

Here is a partial list of the university recreation centers which I visited leading up to and during the aforementioned Concept to Completion steps: Appalachian State, UNCW, Elon, High Point .,ECU, Emory, Notre Dame, Toledo, Ohio U,UNC, Duke, VT, BC, Univ. of Miami, UVA, Washington and Lee, William & Mary, VCU, Miami of Ohio, Georgia Tech, Georgia State, UC Irvine, Cal State Fullerton, Sacramento State, UC San Diego, Cal, UCLA, TCU, North Texas State, SMU, Florida A&M, Univ. of South Carolina, Davidson, Furman, UT, Vanderbilt, Univ of Illinois, Northwestern, Navy, Univ. of Maryland et al.

Here at Wake Forest, after several schematic design iterations — beginning with a stand alone facility and ending with a three story addition and renovation to the existing gymnasium — each of these steps along the way were followed and experienced. Master planning and schematic design moved us closer to opening day.

Next time we will discuss the all-important design development phase and the creation of construction documents. As your business, campus or sports organization looks to you to cast the vision, I hope this series help you to plan the steps to get there.

University Master Plan

University Master Plan